Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that a self-affirmation writing intervention, in which students reflect on personally important values, positively impacts students’ school performance, and there is active research on this intervention. However, this research requires manual coding of students’ writing exercises, and this manual coding has proved to be a time-consuming and expensive undertaking. To assist future self-affirmation intervention studies or educators implementing the writing exercise, we employed our labeled data to fine-tune a pre-trained language model that achieves a comparable level of performance to that of human coders (Cohen’s Kappa: 0.85 between machine coding and human coders as compared to 0.83 between human coders). To explore the potential of more advanced language models without requiring a large training dataset, we also evaluated OpenAI’s GPT-4 in a zero-shot and few-shot classification setting. GPT-4’s zero-shot predictions yield reasonable accuracy but do not reach the fine-tuned BERT model’s performance or human-level agreement. Adding example essays (few-shot prompting) did not appreciably improve GPT-4’s results. Our analysis also finds that the BERT model’s performance is consistent across student subgroups, with minimal disparity between “stereotype-threatened” and “non-threatened” students, which are the focal groups for comparison in the self-affirmation intervention. We further demonstrate the generalizability of the fine-tuned model on an external dataset collected by a different research team: the model maintained a high agreement with human coders (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.86) on this new sample. These results suggest that a fine-tuned transformer model can reliably code self-affirmation essays, thereby reducing the coding burden for future researchers and educators. We make the fine-tuned model publicly available to help the research community automate the burdensome task of coding at https://github.com/visortown/bert-self-affirm

Keywords

Introduction

Stereotype threat refers to the psychological phenomenon in which individuals experience anxiety or underperformance when confronted with a stereotype that is relevant to their social identity (Steele and Aronson, 1995). This phenomenon has been shown to significantly impact academic performance, particularly among marginalized groups. One effective intervention to combat stereotype threat is to have students write exercises that affirm their important beliefs and values (Steele and Liu, 1983; Liu and Steele, 1986), which helps students reflect on positive aspects of their identity to buffer them from the stereotype threat. More recent research has highlighted the efficacy of interventions designed to mitigate the adverse effects of stereotype threat. For instance, value-affirmation exercises, which involve students reflecting on their core beliefs and values, have been demonstrated to buffer against stereotype threat by reinforcing positive aspects of identity (Cohen et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2021; Sherman et al., 2013). These interventions have been particularly effective in educational settings, where they have been shown to reduce achievement gaps and improve long-term academic outcomes (Borman et al., 2018; Goyer et al., 2017; Hanselman et al., 2017).

Analyzing student writing exercises, such as those used in value-affirmation interventions, is critical for understanding the mechanisms through which these interventions operate. Researchers commonly code each essay to determine whether the student’s writing is self-affirming (i.e., the student affirms a personal value) or not. However, manual coding and evaluation of large volumes of text data are labor-intensive, prone to inconsistencies, and often impractical for large-scale studies. In our large-scale study of a self-affirmation intervention (described below), trained human coders needed to read and categorize each student essay, with double-coding of a subset to ensure reliability. This process can become a bottleneck for research and implementation, limiting the scalability of interventions that rely on content analysis of student reflections. Recent work by educational data mining researchers has begun to explore automated approaches to analyzing such essays. For example, Riddle et al. (2015) used natural language processing techniques to examine a corpus of student affirmation essays, identifying distinctive linguistic features used by students from different demographic groups. Their work illustrated that participants with different identities tend to write about values in systematically different ways, providing insight into the psychological mechanisms of the affirmation intervention. However, that study did not attempt to automate the coding of whether an essay was self-affirming; the focus was on linguistic analysis rather than predictive classification. To our knowledge, no prior study has developed an automated classifier to directly replace or augment human coders for identifying self-affirming content in student writing.

Recent advancements in natural language processing (NLP) have provided innovative solutions to these challenges, particularly through the use of pre-trained language models (PTMs). These models, which leverage large-scale unsupervised learning, have revolutionized text analysis by enabling automated, scalable, and consistent classification of textual data (Devlin et al., 2018; Vaswani et al., 2017). Early approaches to automated text analysis relied on traditional machine learning techniques, such as term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) (Razon and Barnden, 2015; Salton and Buckley, 1988), Word2Vec (Mikolov et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2019), and classical algorithms like Naive Bayes (Liu et al., 2018; McCallum and Nigam, 1998), support vector machines (SVMs) (Faulkner, 2014; Cortes and Vapnik, 1995), and random forests (Mathias and Bhattacharyya, 2018; Breiman, 2001). These methods were effective for many tasks but often struggled with capturing complex linguistic patterns and contextual nuances in text.

The emergence of deep learning architectures marked a significant advancement in text analysis. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (Dong and Zhang, 2016) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) (Ruseti et al., 2018; Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997) became popular for their ability to model sequential and spatial relationships in text data. Hybrid models, such as convolutional recurrent neural networks (Dasgupta et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2015), further improved performance by combining the strengths of CNNs and RNNs. Despite these advancements, these models still faced challenges in capturing long-range dependencies and contextual relationships across sentences.

The advent of transformer-based models, such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) (Devlin et al., 2018) and GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) (Brown et al., 2020; Radford et al., 2018), revolutionized NLP. These models utilize self-attention mechanisms (Vaswani et al., 2017)—a technique that allows them to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence relative to each other—to capture contextual relationships within text, enabling them to achieve state-of-the-art performance across a wide range of tasks, including text classification (Beseiso and Alzahrani, 2020; Sun et al., 2019), sentiment analysis (Fernandez et al., 2022), and summarization (Mizumoto and Eguchi, 2023; Lewis et al., 2019). Transformer-based models have also been fine-tuned for domain-specific applications, such as educational text analysis (Assayed et al., 2024; Ludwig et al., 2021), demonstrating their versatility and effectiveness. Recent studies have also examined the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) in educational assessment tasks beyond essay scoring, such as evaluating classroom discussion quality (Tran et al., 2024).

Despite the promise of large PTMs, such as PaLM and GPT-4, their application in educational research is often constrained by computational resources and data privacy concerns, as these models typically require uploading sensitive data to external servers. Consequently, smaller PTMs, such as BERT and GPT-2, have emerged as viable alternatives for researchers working with confidential datasets. While larger models generally yield higher accuracy (Zhao et al., 2023; Zhong et al., 2021), smaller PTMs can achieve comparable performance when fine-tuned on domain-specific data, making them suitable for tasks where human-level accuracy is the benchmark (Aralimatti et al., 2025; Firoozi, 2023; Ye et al., 2024).

In this study, we focus on fine-tuning smaller PTMs to analyze student writing exercises, with the goal of achieving accuracy levels comparable to human coders. By leveraging the efficiency and scalability of these models, along with human coder validation on a random sample, we aim to provide a robust framework for automating the coding of value-affirmation interventions while addressing the practical and ethical challenges associated with computational costs and data privacy. We also compare the BERT model’s performance to that of a more traditional machine learning approach (a Naive Bayes text classifier) to quantify the advantage of using advanced NLP. Furthermore, responding to recent developments and reviewer feedback, we explore the capabilities of a state-of-the-art generative model (GPT-4) in this classification task by using it in a prompt-based zero-shot/few-shot setting. This additional experiment allows us to gauge whether the latest LLMs can match fine-tuned models without task-specific training, providing insight into an alternative approach for automating qualitative coding.

Our work contributes to the growing literature on transformer-based text classification in educational data mining by demonstrating a novel application in the context of psychological interventions. Prior studies have successfully applied models like BERT to tasks such as automated essay scoring (Wang et al., 2022; Xue et al., 2021), short-answer grading in tutoring contexts (Kakarla et al., 2025), and general writing quality assessment (Chen et al., 2024; ElMassry et al., 2025). Kakarla et al. (2025) fine-tuned BERT-based classifiers to evaluate open-response answers in an equity-focused tutor training setting and found that it outperformed GPT-4, while Wang et al. (2022) introduced a multi-scale BERT representation to score essays on coherence and content relevance. Similarly, Chen et al. (2024) used a multi-task BERT model to score multiple dimensions of student essays, and Xue et al. (2021) leveraged a hierarchical BERT approach to jointly assess holistic and analytic writing traits. A recent systematic review by ElMassry et al. (2025) further highlights that transformer models have been employed to classify attributes like sentiment and topic relevance in educational texts. These studies demonstrate the utility of pre-trained transformers for well-defined tasks with clear linguistic markers.

In contrast, our study targets a more abstract and psychologically grounded construct: identifying self-affirming attributes in student writing. This task requires detecting subtle expressions of personal value affirmation, which may be implicit, context-dependent, and linguistically diverse. To our knowledge, no prior work has developed a predictive classifier for this construct. Riddle et al. (2015) conducted descriptive text mining on self-affirmation essays to uncover linguistic patterns across demographic groups but did not attempt automated classification. Our work extends this line of research by moving from descriptive analysis to predictive modeling, enabling scalable and replicable coding of self-affirmation content.

Finally, we note that while no existing computational methods have been published for identifying self-affirming attributes beyond human annotation, our publicly available model and code now offer a reproducible tool for researchers and practitioners. This contribution has practical significance for scaling interventions: automated coding can dramatically reduce the human effort required to implement large-scale self-affirmation exercises or similar activities involving open-ended student responses.

In the following sections, we describe the data and methods, present the model’s performance (including subgroup analyses and comparisons to humans and other automatic coding methods), and discuss implications, limitations, and future directions.

Methodology

Research Questions

This study addresses the following research question: can a fine-tuned PTM achieve performance levels comparable to human coders in classifying student writing exercises for self-affirming attributes? To answer this question, we employed a systematic approach to model selection, training, validation, and evaluation, ensuring methodological rigor and alignment with recent advancements in NLP. We also pose a secondary research question: can a cutting-edge large language model (GPT-4) achieve similar classification performance through zero-shot or few-shot prompting? This question is exploratory and is intended to assess an alternative approach that does not require task-specific fine-tuning.

Model Selection

We selected BERT as the foundational model for this study due to its proven effectiveness in text classification tasks and its ability to capture bidirectional contextual relationships within text (Devlin et al., 2018). We illustrate a practical and replicable process for developing a production-level classifier under a structured analytic framework: establish a baseline, select and train a suitable model, evaluate against human coding standards, and apply the trained model in a separate project. Our goal was not to exhaustively compare all potential transformer-based models, but rather to demonstrate how one can arrive at a high-performing, deployable solution using a well-established architecture.

Specifically, we used the BERT-base (uncased) configuration, which includes 12 transformer layers and a 768-dimensional hidden size. BERT was an appealing choice for several reasons. BERT is pre-trained on a large corpus of text data, including 2,500 million words from English Wikipedia and 800 million words from BookCorpus, using a masked language modeling objective. During pre-training, random words in the input text are masked, and the model learns to predict these masked words based on their surrounding context. This process enables BERT to develop a deep understanding of language structure and semantics, which can be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks, such as text classification, sentiment analysis, or question-answering.

We chose BERT over other transformer-based models for several reasons. First, BERT is one of the most widely used and well-documented PTMs in academic research, particularly for text classification tasks (Han et al., 2021). Second, its bidirectional architecture allows it to capture complex contextual relationships, making it particularly suitable for analyzing nuanced student writing exercises. Third, we selected BERT as a middle-ground model that balances performance with computational feasibility: larger models like GPT-3 or GPT-4 were not viable to fine-tune on our data at the time of the study due to computational resource constraints and data privacy concerns, while BERT could be fine-tuned on personal computers. While other smaller models (such as GPT-2 or RoBERTa) could also be fine-tuned locally, we did not formally train these alternatives because our fine-tuned BERT model achieved ceiling-level performance—matching the reliability of human-coded labels—and it is ready for production. We acknowledge that other transformer variants could have been used and discuss this further in the results and discussion sections.

To establish a clear reference point for evaluating the proposed model, we implemented a classical machine learning baseline: a Naive Bayes classifier using TF-IDF features. Naive Bayes is a well-known, computationally efficient algorithm that has long served as a standard baseline for text classification tasks. Its simplicity, interpretability, and surprisingly strong performance on bag-of-words representations make it a suitable benchmark for student writing data, where datasets may be relatively small or noisy. Although other shallow models such as logistic regression, SVM, or random forests were considered, prior research and preliminary experiments indicated that these models typically achieve comparable results to a tuned Naive Bayes classifier (Pranckevičius and Marcinkevičius, 2017; Rennie et al., 2003).[1] Therefore, we selected the Naive Bayes model as the primary baseline. This allows us to focus on assessing the extent to which the proposed BERT-based model provides meaningful performance gains beyond traditional, lightweight approaches commonly used in educational NLP tasks.

Finally, to explore the use of LLMs without fine-tuning, we selected OpenAI’s GPT-4 as an exemplar state-of-the-art model for a secondary analysis. GPT-4 is a much larger model (with hundreds of billions of parameters, exact number unpublished) that has shown human-level performance on various benchmarks in zero-shot or few-shot settings. We did not train or fine-tune GPT-4 on our data; instead, we treated GPT-4 as an “off-the-shelf” classifier by carefully designing prompts to instruct it to categorize essays. The model was accessed via a secure, organization-dedicated server, mitigating any data privacy concerns. This comparison serves to contextualize our fine-tuned BERT model’s performance against a model that has seen vastly more data during pre-training and can perform complex reasoning, albeit without direct training on our task. It also addresses a question of interest: if one had access to GPT-4 via an API, could one skip the entire fine-tuning process and get comparable results through prompting?

Model Training

Training a Naive Bayes Model

To establish a baseline for evaluating the performance of our fine-tuned BERT model, we implemented a Bernoulli Naive Bayes model. This classical machine learning technique, known for its computational efficiency and interpretability, provides a comparative benchmark for assessing the efficacy of advanced PTMs in our specific classification task.

The Naive Bayes model was constructed using the following systematic process. It was implemented as a streamlined pipeline, encapsulating the CountVectorizer, TfidfTransformer, and BernoulliNB classifier within a single object. This pipeline facilitated the seamless integration of feature extraction and model training.

We began by converting the raw text data into numerical representations using the CountVectorizer from the scikit-learn library. This step generated a matrix of token counts, effectively quantifying the presence of words within each student writing exercise. Subsequently, we applied the TfidfTransformer to convert the raw token counts into TF-IDF scores. This transformation adjusted the importance of each word based on its frequency across the entire dataset, mitigating the influence of common terms and highlighting more discriminative features. We used a Bernoulli Naive Bayes model, which is an appropriate choice for binary feature representations, where features are indicative of word presence or absence. It predicts the probability of a certain class based on the presence or absence of these features. The formula it follows is:

The pipeline was trained using the training subset of our labeled dataset, enabling the model to learn the probabilistic relationships between text features and the target classification labels.

We evaluated the trained Naive Bayes model on the validation dataset to assess its predictive performance. The data was split into a training set (80%) and a validation set (20%) using stratified sampling to preserve class proportions. To ensure reproducibility, we used a fixed random state. The model’s performance was measured using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, providing a comprehensive assessment of its ability to classify student writing exercises accurately.

We also calculated Cohen’s Kappa to account for the likelihood of classification occurring by chance. A classification report was generated to provide a detailed overview of the model’s performance across the two classes (general and self-affirming).

The trained model was then used to make predictions on the out-of-sample comparison dataset, providing further information about the model’s generalizability.

GPT-4 Prompting Experiment

We conducted an experiment using GPT-4 to classify the essays without fine-tuning. We treated this as a zero-shot/few-shot inference problem. To use GPT-4, we formulated a prompt that instructs the model to read a student essay and decide if it is self-affirming or not. In the zero-shot scenario, the prompt was purely an instruction. In few-shot scenarios, we appended a few example essays with their coding labels to the prompt as demonstrations, then asked GPT-4 to label a new essay. We experimented with using 2, 4, and 6 examples, and we varied the example content to include a mix of shorter (1-2 sentences) and longer essays, to see if prompt length or detail affected performance. We ran GPT-4 through an API with temperature=0 (to minimize randomness and get deterministic outputs) and top_p=1 (to ensure the full probability distribution is considered). GPT-4’s outputs were then compared to the human-coded ground truth to compute accuracy and other metrics. The prompt used for GPT-4 classification is provided in the Appendix.

Training a BERT-Based Model

We fine-tuned a BERT model to address our research question regarding the potential of PTMs to match human coding accuracy. This process involved adapting the pre-trained BERT architecture to our specific text classification task, leveraging its deep contextual understanding of language through the following steps:

- Tokenization and Input Encoding: We employed the BERT tokenizer to convert the raw text data into token IDs, attention masks, and segment IDs. This process involved splitting the text into word units, adding special tokens for the beginnings and separations of sentences, and padding sequences to a uniform length. A dedicated function was implemented to efficiently process the input text and generate the necessary input components for the BERT model.

- Model Architecture and Training Setup: A deep learning model was constructed using the Keras framework, with the pre-trained BERT layer serving as the foundational component. The BERT layer’s weights were frozen to preserve its pre-trained knowledge, while an additional dense output layer with a sigmoid activation function was added for binary classification. The model was compiled using binary cross-entropy loss, the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 2e-6, and the performance metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Handling Imbalanced Data with Class Weights: To mitigate the impact of class imbalance, class weights were dynamically computed based on the label distribution within the training dataset. This ensured that the model gave appropriate weight to underrepresented classes during training.

- Model Training and Early Stopping: The model was trained using a batch size of 16 and a maximum of 100 epochs, with a 20% validation split for monitoring performance. Early stopping was implemented based on validation loss to prevent overfitting and optimize the model’s generalization capabilities. The training history was saved for later analysis.

- Model Saving and Predictions: The trained model was saved as a Keras file, enabling its reuse for subsequent predictions. Predictions were performed on the out-of-sample comparison dataset by encoding the text data and applying a threshold of 0.5 to the model’s output probabilities.

Validation

To ensure the reliability and generalizability of our results, we adopted a rigorous approach to model training and validation. The labeled dataset, which had been coded by project staff, was divided into three subsets:

- Training Set (80% of the data): Used to fine-tune the BERT model.

- Validation Set (20% of the data): Used to evaluate the model’s performance during development and to prevent overfitting.

- Out-of-Sample Comparison Dataset: Comprising cases that were double-coded by human coders, this dataset was reserved for final evaluation and was not used during model development.

The fine-tuning process involved adapting BERT’s pre-trained weights to our specific task of classifying self-affirming attributes in student writing. We employed a standard fine-tuning protocol, optimizing the model using a cross-entropy loss function and a learning rate of 2e-6. To assess the model’s performance, we computed several evaluation metrics, including:

Accuracy, which measures the proportion of correctly classified instances as

Precision, which indicates the model’s ability to avoid false positives as

Recall, which reflects the model’s ability to identify all relevant instances as

And F1 Score, which Provides a balanced measure of precision and recall as

Here, TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The F1 score was prioritized as a key metric due to its ability to balance precision and recall, making it particularly suitable for evaluating binary classification tasks.

Evaluation

To evaluate the fine-tuned model’s performance, we applied it to the out-of-sample comparison dataset, which had been double-coded by human coders. This allowed us to compare the model’s predictions with human judgments, providing a robust benchmark for assessing its effectiveness. We computed interrater reliability using Cohen’s Kappa to measure agreement between:

- The original coders and the double coders

- The original coders and the machine model

- The double coders and the machine model

Additionally, we compared the fine-tuned BERT model’s performance to a Naive Bayes baseline model. Naive Bayes is a probabilistic model that assumes feature independence and applies Bayes’ theorem to make predictions. While it is computationally efficient and straightforward, its simplicity often limits its performance on complex tasks. By comparing BERT to this baseline, we aimed to highlight the advantages of using advanced PTMs for text classification tasks.

We further conducted McNemar’s tests (Agresti, 2002), which are appropriate for comparing paired model predictions, as they evaluate whether the proportion of differing predictions between two classifiers is symmetric. The McNemar’s test statistic is defined as:

where is number of instances where Model A is correct and Model B is wrong, and is number of instances where Model A is wrong and Model B is correct.

This comprehensive evaluation approach allowed us to directly compare the performance of our fine-tuned BERT model and the Naive Bayes baseline with human coding standards, thus addressing our research question regarding the comparability of machine and human classification accuracy.

Data Sources

The data come from a large-scale randomized controlled trial that assigned students to either a treatment or control condition within each school, with stratification by race/ethnicity when such data were available at the time of random assignment. The intervention study includes three cohorts of 7th-grade students during the 2019–2020, 2020–2021, and 2021–2022 school years.

The treatment consists of three or four 15-minute in-class writing exercises in which students choose two or three personally important values from a list of 11 (e.g., family, music, sports) and write about why those values are important to them. Control students engage in the same amount of writing but are asked to write about neutral topics. Teachers—who were blind to the randomization and the true purpose of the exercises—distributed intervention materials as if they were regular classroom activities. All students were also blind to their experimental condition and to the hypotheses of the study.

Within the study, only the first two writing exercises—administered during the first semester—were coded, as the intervention’s impacts on school performance were evaluated during the same school year the exercises were administered. Each exercise took students approximately 15 minutes to complete, with an average response length of 71 words.

Students’ writing was coded as self-affirming if the student affirmed a value (i.e., wrote about it being important, for example, because the student enjoys it or is good at it). Responses were coded as having affirmed a value if the coder determined that the student discussed a value in terms of its importance to them (e.g., using phrases like “like,” “love,” “care about,” “good at,” or “best at”). This coding scheme was initially developed based on self-affirmation theory as part of a content analysis of a random subsample of the responses.

Coders were trained using this scheme to determine whether the writing showed evidence of self-affirmation. After initial practice coding, coders were convened by researchers to review and clarify uncertain cases. Using the final coding scheme, student exercises were assigned to trained coders, with a random subset of responses rated by two coders to assess inter-coder reliability. Coders were blind to the exercise’s experimental condition and to each other’s ratings in double-coded cases. Coder agreement was substantial for the self-affirmation construct ().

The three cohorts include 12,212 students in 34 schools in 12 districts across 8 states. The final analytical sample includes writing samples from 7,239 students, with two exercises coming from 3,319 students.[2] The analytical samples are diverse with 73% classified as economically disadvantaged, 8% classified as English language learners, 10% classified as students with individualized educational plans, 23% African American, 25% Hispanic, 45% white, and 6% other racial/ethnic groups (see Table 1).

Characteristics | Percent | Characteristics | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

7th Grade Cohort (N = 7,239) | Race/ethnicity (N = 7,107) | ||

SY2019-2020 | 30 | White | 45 |

SY2020-2021 | 45 | Black | 23 |

SY2021-2022 | 25 | Hispanic | 25 |

|

| Other | 7 |

Free or Reduced-Price Lunch (N = 7,086) | English Learner (N = 7,064) | ||

Yes | 27 | Yes | 8 |

No | 73 | No | 92 |

Sex (N = 6,970) | Individualized Educational Plan (N = 7,064) | ||

Male | 49 | Yes | 10 |

Female | 51 | No | 90 |

Results

Model Performance Comparison

This section focuses primarily on comparing the performance of a traditional machine learning baseline (Naive Bayes) with a fine-tuned transformer-based model (BERT). The goal of this comparison is to evaluate the extent to which domain-specific fine-tuning and contextual language representations improve classification performance. Although the full results of the GPT-4 experiment are presented separately in Section 3.3, results from one representative GPT-4 condition (instructions only) are included in Table 2 as a brief point of reference. This limited inclusion serves as a quick performance benchmark.

The fine-tuned BERT model demonstrated superior performance compared to the baseline Naive Bayes model and GPT-4, as shown in Table 2. The Naive Bayes model achieved an accuracy of 0.86 and an F1 score of 0.88, indicating respectable performance for a traditional machine learning approach. GPT-4 with instructions only achieved somewhat better accuracy of 0.90 and an F1 score of 0.93, indicating stronger inference capability without training data (with similar performance using different sets of examples, as discussed in Section 3.3). In contrast, the BERT model achieved an accuracy of 0.93 and an F1 score of 0.95, reflecting its advanced capability to capture nuanced patterns in the text data. These results underscore the effectiveness of transformer-based models like BERT in handling complex classification tasks, particularly in educational contexts where textual data often contains subtle and context-dependent meanings. Furthermore, preliminary explorations with GPT-2 achieved comparable performance (Accuracy: 0.92; F1 Score: 0.94), suggesting that large pre-trained language models broadly possess the advanced capability to capture these nuanced textual patterns.

Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Naive Bayes | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.88 |

GPT-4 (instructions only) | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

BERT | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

To assess potential algorithmic bias, we further analyzed model performance by stereotype-threatened status (Table 3). This analysis is particularly important given the study’s focus on stereotype threat among Black and Hispanic students. The results indicate that while the Naive Bayes model exhibited performance discrepancies between threatened and non-threatened students, the BERT model maintained consistent performance across both groups.

Model | Subgroup | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Naive Bayes | Threatened | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.90 |

Non-threatened | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.87 | |

BERT | Threatened | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

Non-threatened | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.95 | |

Naive Bayes | Female | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

Male | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.85 | |

BERT | Female | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

Male | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.95 | |

Naive Bayes | FRPL* | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

Non-FRPL | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.89 | |

BERT | FRPL | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

Non-FRPL | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

Note: *Students who were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

For stereotype-threatened students (Black and Hispanic students), the Naive Bayes model achieved an accuracy of 0.88, with a relatively high precision of 0.93, but a lower recall of 0.87, leading to an F1 score of 0.90. This suggests that Naive Bayes made highly precise predictions but missed a considerable number of relevant cases. In contrast, BERT demonstrated higher accuracy (0.92), more balanced precision (0.93), significantly improved recall (0.98), and a stronger F1 score (0.95), indicating a more equitable and effective classification of threatened students.

For non-threatened students (White, Asian, Multirace, and American Indian), BERT also performed slightly better than Naive Bayes. The Naive Bayes model achieved 0.86 accuracy, 0.92 precision, 0.83 recall, and an F1 score of 0.87, whereas BERT attained 0.94 accuracy, 0.92 precision, 0.98 recall, and an F1 score of 0.95. BERT’s higher recall (0.98 vs. 0.83) suggests it was better at identifying relevant cases, ensuring fewer misclassified instances.

These findings highlight BERT’s fairness and reliability in classification tasks involving stereotype-threatened groups. Unlike Naive Bayes, which demonstrated higher precision but lower recall for threatened students, BERT maintained strong and balanced precision and recall across both groups, mitigating disparities in performance. These results reinforce BERT’s potential for unbiased and effective text classification in educational research, particularly in studies of stereotype threat, where equitable model performance is critical.

The fairness of the model was further examined across key demographic dimensions, specifically gender and socioeconomic status (proxied by eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch). The analysis found no notable performance gaps across these subgroups; the BERT model maintained consistently high accuracy, clustering around 93–95% for essays written by both male and female students, and exhibiting similarly strong performance for students who were and were not eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL). Due to the limited sample sizes required for reliable statistical comparison, this analysis was not carried out for English learners and students with an Individualized Educational Plan.

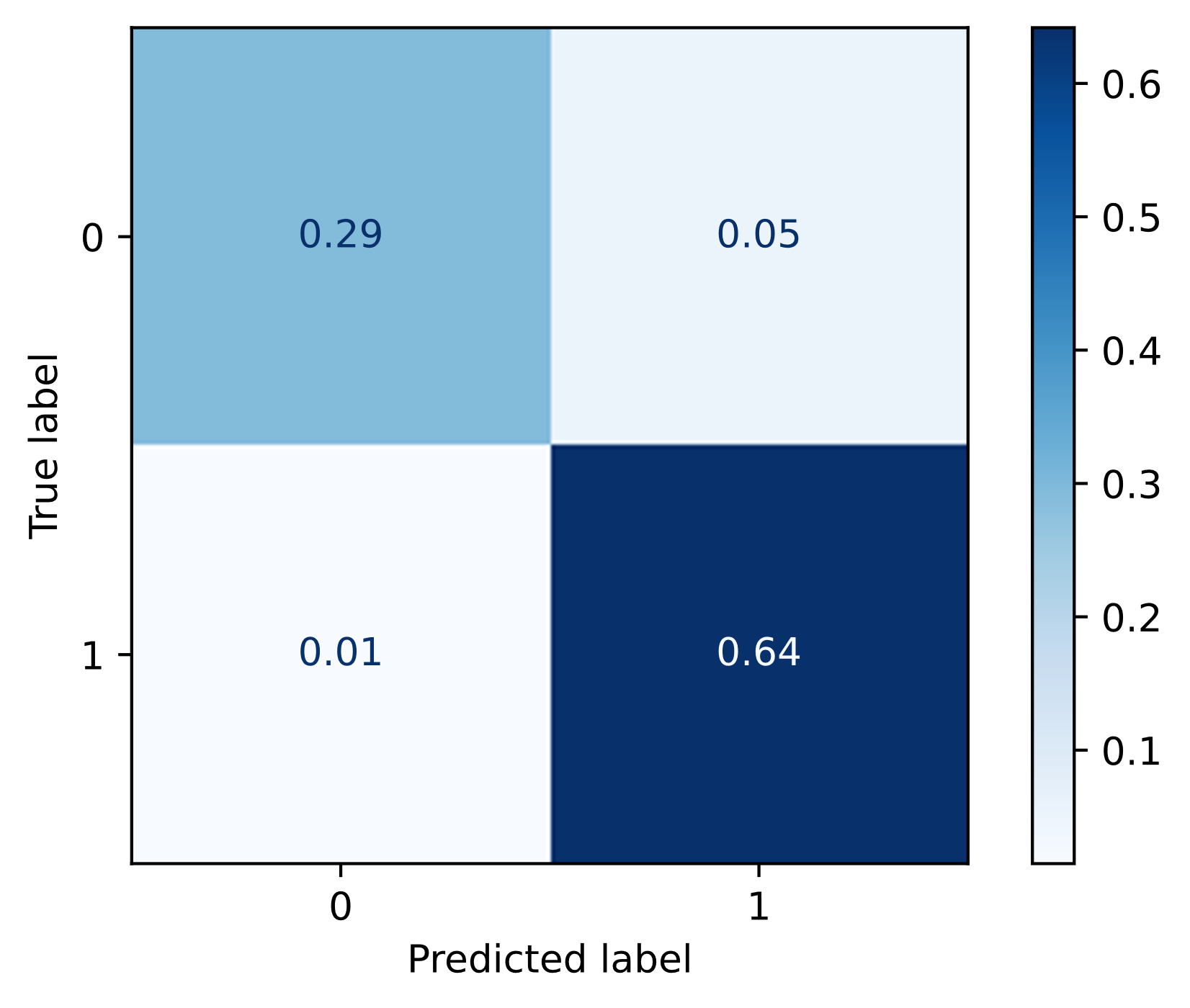

The confusion matrix for the BERT model (Figure 1) provides further insights into its classification behavior. The model exhibited a higher number of false positives (0.05) compared to false negatives (0.01) for the self-affirming attribute. This indicates that the model is marginally more likely to classify essays as self-affirming, even when they are not. While this tendency is minimal, it highlights the importance of carefully interpreting model predictions, particularly in contexts where false positives could have implications for intervention design or student assessment.

However, a closer analysis reveals that in the majority of disagreement cases (6 out of 9), the model’s predictions aligned with those from a second round of human coding, which, upon review, provided more reasonable codings than the initial round. For instance, Student #2 wrote about enjoying music, Student #3 emphasized living in the moment, and Student #5 described participating in sports and having fun—all expressions of personal values and self-identity. While the original human coder marked these as non-self-affirming, both the model and the double human coding correctly identified them as self-affirming.

Conversely, in the remaining three disagreement cases, the model diverged from both human coders. Student #1 wrote about another person’s interest in drawing, Student #4 offered a generalized analysis of social group types, and Student #8 described gameplay mechanics. These examples lack personal self-reflection and thus, according to our review, should be classified as general. The model misclassified two responses (Students #1 and #8) as self-affirming while the human coders correctly classified them as general, and correctly classified one response (Student #4) as general while the human coders misclassified it as self-affirming. These results indicate that the model’s performance is mixed in edge cases.

Finally, we conducted McNemar’s tests to statistically compare BERT and Naive Bayes on the paired classification outcomes. Using the original human coders as the ground truth, BERT correctly classified 125 of the 134 cases, compared to 119 correctly classified by the Naive Bayes model. The McNemar’s test based on their paired predictions ( = 6, = 12) yielded a test statistic of 1.39 and a p-value of 0.167, indicating that the difference in accuracy between the two models was not statistically significant. However, when using the human double coders as the ground truth, BERT correctly classified 127 cases and Naive Bayes 115. In this comparison ( = 3, = 15), McNemar’s test produced a test statistic of 6.72 and a p-value of 0.004, suggesting that BERT performed significantly better than the Naive Bayes model at the 0.01 level. In addition, while paired t-tests showed that the coding agreement between BERT and the original human coders (t = 1.68, p = 0.10) and between Naive Bayes and the double human coders were not statistically significant (t = 1.82, p = 0.07). While the coding agreement between BERT and the double human coders was also not statistically significant (t = 1.14, p = 0.26), the coding agreement between Naive Bayes and the double human coders was statistically significant (t = 2.09, p < 0.05).

Student # | Student Writing Exercise | Human Coder | Double Human Coder | Model Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Art is important to (name) because he likes drawing. He also like to draw a bunch of different characters from different movies. He also likes to draw all the different characters from Batman. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

2 | I love listening to music because if I'm not I tend to get off task. I love to be with family and friends and (about 10 words suppressed) I made a lot of new friends here. I like making people laugh because when they are sad I know how to cheer them up. | 0 | 1 | 1 |

3 | I say living in the moment because I want to come to school and enjoy my day and not let nobody ruin it . Also I say independent because I dont want anybody distracting me from what I go to do affecting my grades . | 0 | 1 | 1 |

4 | Whenever I meet new people, I can tell if they are in a specific group of person, or are they independent, many people are in the category of "Trendy". (about 50 words describing the group). Then there are the "Nerds". (about 150 words describing the group) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

5 | (several) days ago, i went to my friends house for his birthday party, also i play sports, and i love to have fun. | 0 | 1 | 1 |

6 | My brother loves sports. He loves (names of sports), and just about anything that looks cool to him. But it can't be boring or slow, it HAS to be fast. So sports like (names of sports) are out of the question... (Additional about 500 words describing the brother) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

7 | Being with friends or family because when you are alone it gets scary and you need them to have fun. Making art because when you bored you can make art, and it is so fun, and it's a good way to get o your mind off things. | 0 | 1 | 1 |

8 | playing (name of a game) is very fun and you can go very late game if you know how to go late game... | 0 | 0 | 1 |

9 | They are important to me because these are somethings i will choose to do in the future and make alot of money. | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Note: Shaded rows indicate that the model prediction is different from both human coders. Italicized words in parentheses explain the omission of portions of the text.

Interrater Reliability

To evaluate the agreement between the model predictions and human coders, we computed Cohen’s Kappa, a robust measure of interrater reliability. As shown in Table 5, the BERT model achieved almost perfect agreement with human coders, with Cohen’s Kappa values of 0.85 when compared to both the original coders and the double coders. In contrast, the Naive Bayes model demonstrated substantial agreement, with Cohen’s Kappa values of 0.76 and 0.70 when compared to the original and double coders, respectively. These findings align with established thresholds for interpreting Cohen’s Kappa (McHugh, 2012), where values above 0.80 indicate almost perfect agreement. This high level of agreement suggests that the fine-tuned BERT model can serve as a reliable alternative to human coders in classifying self-affirming attributes in student writing. Furthermore, preliminary explorations using GPT-2 also showed strong reliability, demonstrating substantial agreement with human coders (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.82), further indicating the potential of LLMs to capture these nuanced textual patterns.

Comparison | Cohen’s Kappa (N = 134) |

|---|---|

Original coders vs. double coders Naive Bayes vs. original coders Naive Bayes vs. double coders BERT vs. original coders BERT vs. double coders | 0.83 0.76 0.69 0.85 0.85 |

GPT-4 Classification Performance

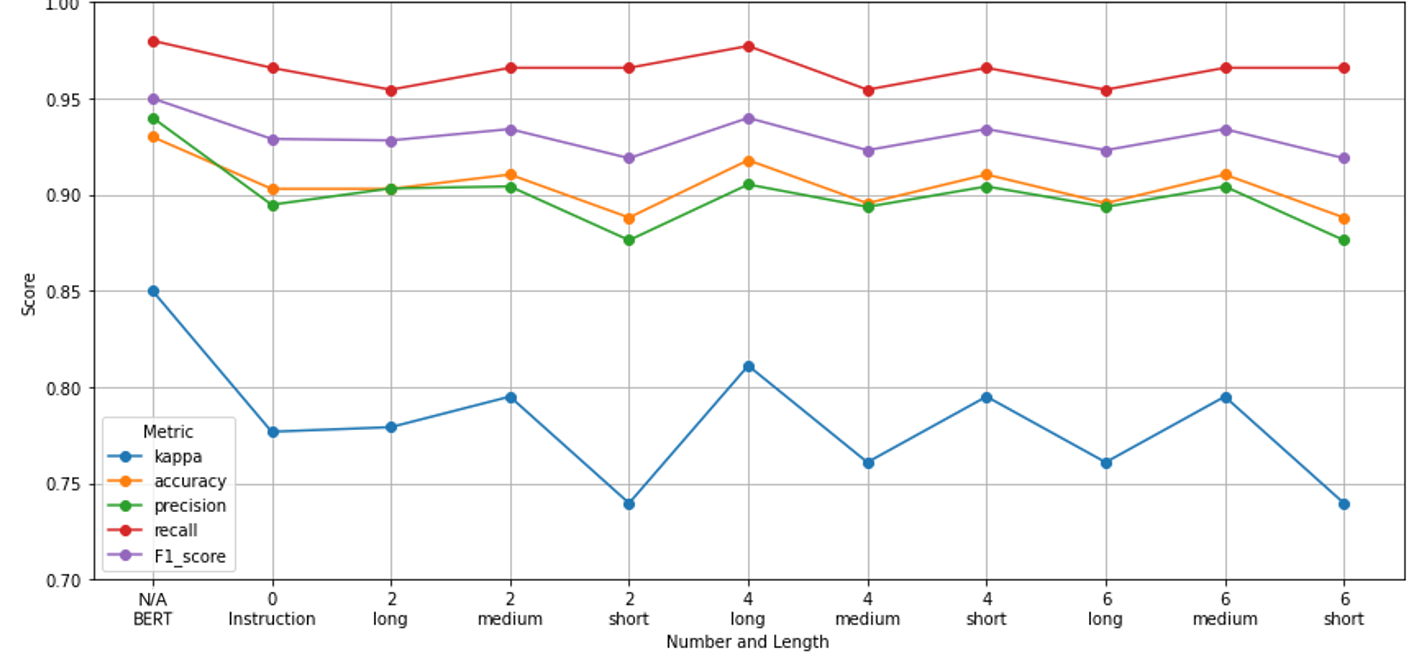

We now turn to the findings from our GPT-4 experiment. Using the zero-shot prompting approach described earlier, GPT-4 was able to classify the essays with a decent degree of accuracy, but it did not reach the performance of the fine-tuned BERT model. Figure 2 shows a comparison of performance between GPT-4 and BERT. On the same test set of essays, GPT-4 achieved an accuracy of 0.90, with a precision of 0.89, recall of 0.97, and F1 of 0.93. In other words, GPT-4 matched the Naive Bayes baseline’s level of performance and was somewhat lower than BERT. The pattern of errors for GPT-4 was broadly similar to that of BERT in that it tended to misclassify some essays lacking explicit self-affirmation as affirming when the writing was enthusiastic or positive. GPT-4’s classifications had a Cohen’s Kappa of approximately 0.78 with human coders. These were categorized as “substantial agreement,” a bit below the threshold of human-human agreement.

Interestingly, providing GPT-4 with example essays (few-shot prompting) did not significantly improve its performance. We tried up to 6 examples with representative texts, but GPT-4’s accuracy remained in the 0.89–0.91 range. We replicated this setup with alternative example sets and it yielded similar results. This could imply that GPT-4 already has a strong internal understanding of the task from its pre-training and additional examples did not add much. It might also indicate that GPT-4 struggled with some inherent ambiguity in the task that a few examples cannot resolve. The plateau in performance is consistent with other observations that beyond a certain point, more few-shot examples yield diminishing returns (Tang et al., 2025; Yoshida, 2024).

Generalization to External Data

This study aims to provide a robust framework for automating the coding of value-affirmation interventions for future studies. Automating this process can enhance the scalability and efficiency of self-affirmation research, reducing the burden on human coders while maintaining high reliability and without losing validation from human coders. The framework follows a structured approach: training the model with coded essays, validating the coding reliability by sample human coding, applying the model to new student samples with validation of the coding reliability by sample human coding, and retraining the model with new coded samples to learn about new context if the context shifts. To assess the generalizability of the fine-tuned BERT model, the model was applied to a separate dataset of student writing exercises for another self-affirmation study collected by another research team at a different organization. The study involved 7th-grade students during the 2023-2024 school year. Students took approximately 15 minutes to complete each exercise and wrote an average of 66 words. The exercise data includes 4,660 students from 25 schools in 3 districts across 3 states, representing a diverse population: 47.4% were classified as economically disadvantaged (only one district, which contributed 1398 essays, reported data on economically disadvantaged status), 12.4% as English language learners, 0.8% as students with individualized education plans, 7.3% African American, 41.1% Hispanic, 40.6% white, and 11% from other racial/ethnic groups. The subsample for reliability coding was a random sample stratified by district, condition, race/ethnicity, ELL status, and gender. The model achieved a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.86 with human coders (n = 150), indicating almost perfect agreement (McHugh, 2012). This strong performance on an external dataset underscores the model’s robustness and its potential for future applications.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that fine-tuned PTMs, such as BERT, can achieve performance levels comparable to human coders in classifying self-affirming attributes in student writing. We did not further assess larger or newer models because, given that BERT achieved near-perfect agreement with human coders (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.85), further optimization through newer architectures may yield diminishing returns. This finding has significant implications for educational research, particularly in the context of stereotype threat interventions. By automating the coding process, researchers can analyze large volumes of text data more efficiently, reducing the time and cost associated with manual coding. Moreover, the ability to generalize the model to external datasets suggests that it can be adapted to diverse educational contexts, making it a valuable tool for scaling up self-affirmation interventions and other related text-based analyses.

We did not fine-tune or evaluate extremely large models (like GPT-3 or GPT-4) in the original design of this study, primarily due to concerns about resources and privacy. Interestingly, since we completed the initial work, GPT-4 became available through a secure dedicated server, allowing us to experiment with it via prompting. GPT-4’s performance, while reasonable, did not match the fine-tuned BERT. This finding is similar to Kakarla et al. (2025) who found fine-tuned BERT-based classifiers outperformed GPT-4 in evaluating open-response answers in an equity-focused tutor training setting. This suggests that, at least for our classification task, meticulous fine-tuning of a mid-sized model was more effective than prompting a very large model. It’s possible that fine-tuning GPT-4 (if it were possible) would achieve similar or higher performance, but it might be overkill given that the fine-tuned BERT already achieves high enough accuracy for practical deployment. Other mid-size models with transformer architectures (e.g., GPT-2, RoBERTa) might also achieve similar performance using the training data. The success we found with BERT likely could be replicated with those other models, as long as they are pre-trained on large corpora and fine-tuned appropriately. Ultimately, one insight here is that for well-defined classification tasks with ample labeled data, fine-tuning a model specifically for the task is a very effective approach, even in an era where one might be tempted to rely solely on pre-trained LLMs.

The fine-tuned BERT model offers a practical solution for educators and researchers seeking to evaluate the effectiveness of self-affirmation exercises. By leveraging machine learning, stakeholders can gain insights into student writing without the need for extensive manual coding. This approach not only enhances the scalability of interventions but also enables more timely feedback, which is critical for supporting student development. Additionally, the model’s performance on a diverse dataset highlights its potential for use in varied educational settings, including those serving economically disadvantaged or culturally diverse populations. However, we strongly recommend that researchers double-code a random sample of the data to ensure reliability when using the fine-tuned model in their work. Complementing this work, recent research has shown that PTMs can also provide feedback on instructional quality, achieving accuracy levels that approach human inter-rater reliability (Whitehill and LoCasale-Crouch, 2024). Together, these advancements highlight the growing potential of AI-driven tools to enhance both student assessment and instructional support in educational settings.

While the results are promising and our analysis by different demographic characteristics did not reveal substantial performance differences, it is essential to address potential biases in the training data and model predictions. Researchers must remain vigilant about the ethical implications of deploying machine learning models in educational settings, ensuring that they do not inadvertently reinforce existing biases or inequities. Strategies for bias mitigation, such as regular audits of model performance and the inclusion of diverse training data, should be prioritized to promote equitable outcomes.

This study opens several avenues for future research. First, exploring the application of other transformer-based models, such as GPT-2 or RoBERTa, could provide further insights into the relative strengths and limitations of different architectures. Second, investigating the model’s performance on other types of educational text data, such as reflective journals or peer feedback, could expand its utility. Finally, developing user-friendly interfaces for educators to access and use the model could facilitate its adoption in real-world settings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) under Grant #R305A180230: Reducing Achievement Gaps at Scale Through a Brief Self-Affirmation Intervention. All conclusions and opinions are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the IES. The authors thank colleagues at WestEd for sharing statistics from their coding results and sample descriptives to assess the generalizability of the fine-tuned BERT model. We also acknowledge the contributions of the coding team in labeling the dataset, and we are grateful for the helpful feedback from the reviewers, which substantially improved this manuscript.

Declaration of Generative AI Software tools in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in all the sections in order to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Agresti, Alan. 2002. Categorical Data Analysis. Hooken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-36093-3.

- Aralimatti, R., Shakhadri, S. A. G., KR, K., and Angadi, K. B. 2025. Fine-Tuning Small Language Models for Domain-Specific AI: An Edge AI Perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.01933.

- Assayed, S. K., Alkhatib, M., and Shaalan, K. 2024. A Transformer-Based Generative AI Model in Education: Fine-Tuning BERT for Domain-Specific in Student Advising. In Breaking Barriers with Generative Intelligence, A. Basiouni, and C. Frasson, Eds. Using GI to Improve Human Education and Well-Being. BBGI 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 2162. Springer, Cham, 165–174.

- Beseiso, M., and Alzahrani, S. 2020. An empirical analysis of BERT embedding for automated essay scoring. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 11(10), 204–210.

- Borman, G. D., Grigg, J., Rozek, C. S., Hanselman, P., and Dewey, N. A. 2018. Self-affirmation effects are produced by school context, student engagement with the intervention, and time: Lessons from a district-wide implementation. Psychological Science, 29(11), 1773–1784.

- Breiman, L. 2001. Random forests. Machine learning, 45, 5–32.

- Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A. and Agarwal, S. and Amodei, D. 2020. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33, 1877–1901.

- Chen, S., Lan, Y., and Yuan, Z. 2024. A multi-task automated assessment system for essay scoring. In Artificial Intelligence in Education, A. M. Olney, I. A. Chounta, Z. Liu, O. C. Santos, and I. I. Bittencourt, Eds. AIED 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 14830. Springer, Cham, 276–283.

- Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Apfel, N., and Master, A. 2006. Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science, 313(5791), 1307–1310.

- Cortes, C., and Vapnik, V. 1995. Support-vector networks. Machine learning, 20, 273–297.

- Dasgupta, T., Naskar, A., Dey, L., and Saha, R. 2018. Augmenting textual qualitative features in deep convolution recurrent neural network for automatic essay scoring. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Natural Language Processing Techniques for Educational Applications, Y. Tseng, H. Chen, V. Ng, and M. Komachi, Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 93–102.

- Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., and Toutanova, K. 2018. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805.

- Dong, F., and Zhang, Y. 2016. Automatic features for essay scoring–an empirical study. In Proceedings of the 2016 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, J. Su, K. Duh, and X. Carreras, Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 1072–1077.

- ElMassry, A. M., Zaki, N., AlSheikh, N., and Mediani, M. 2025. A Systematic Review of Pretrained Models in Automated Essay Scoring. IEEE Access, 13, 121902-121917.

- Faulkner, A. 2014. Automated classification of stance in student essays: An approach using stance target information and the Wikipedia link-based measure. In The Twenty-Seventh International Flairs Conference, W. Eberle, and C. Boonthum-Denecke, Eds. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 174-179.

- Fernandez, N., Ghosh, A., Liu, N., Wang, Z., Choffin, B., Baraniuk, R., and Lan, A. 2022. Automated scoring for reading comprehension via in-context BERT tuning. In Artificial Intelligence in Education, M. M. Rodrigo, N. Matsuda, A. I. Cristea, and V. Dimitrova, Eds. AIED 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13355. Springer, Cham, 691–697.

- Firoozi, T. 2023. Using Automated Procedures to Score Written Essays in Persian: An Application of the Multilingual BERT System (Doctoral dissertation). University of Alberta.

- Goyer, J. P., Garcia, J., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Binning, K. R., Cook, J. E., Reeves, S. L., Apfel, N., Taborsky-Barba, S., Sherman, D.K., and Cohen, G. L. 2017. Self-affirmation facilitates minority middle schoolers' progress along college trajectories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(29), 7594–7599.

- Han, X., Zhang, Z., Ding, N., Gu, Y., Liu, X., Huo, Y., Qiu, J., Yao, Y., Zhang, A., Zhang, L. and Han, W. 2021. Pre-trained models: Past, present and future. AI Open, 2, 225–250.

- Hanselman, P., Rozek, C., Grigg, J., Pyne, J., and Borman, G. D. 2017. New evidence on self-affirmation effects and theorized sources of heterogeneity from large-scale replications. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(3), 405–424.

- Hochreiter, S., and Schmidhuber, J. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8), 1735–1780.

- Kakarla, S., Borchers, C., Thomas, D., Bhushan, S., and Koedinger, K. R. 2025. Comparing few-shot prompting of GPT-4 LLMs with BERT classifiers for open-response assessment in tutor equity training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.06658.

- Kumar, Y., Aggarwal, S., Mahata, D., Shah, R. R., Kumaraguru, P., and Zimmermann, R. 2019. Get it scored using autosas—an automated system for scoring short answers. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, P. V. Hentenryck, and Z. Zhou, Eds. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 33(01), 9662–9669.

- Lewis, M., Liu, Y., Goyal, N., Ghazvininejad, M., Mohamed, A., Levy, O., Stoyanov, V. and Zettlemoyer, L. 2019. Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.13461.

- Liu, Q., Zhang, S., Wang, Q., and Chen, W. 2018. Mining online discussion data for understanding teachers’ reflective thinking. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 11(2), 243–254.

- Liu, S., Liu, P., Wang, M., and Zhang, B. 2021. Effectiveness of stereotype threat interventions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(6), 921–949.

- Liu, T. J., and Steele, C. M. 1986. Attributional analysis as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 531–540.

- Ludwig, S., Mayer, C., Hansen, C., Eilers, K., and Brandt, S. 2021. Automated essay scoring using transformer models. Psych, 3(4), 897–915.

- Mathias, S., and Bhattacharyya, P. 2018. ASAP++: Enriching the ASAP automated essay grading dataset with essay attribute scores. In Proceedings of the eleventh international conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC 2018), N. Calzolari, K. Choukri, C. Cieri, T. Declerck, S. Goggi, K. Hasida, H. Isahara, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, H. Mazo, A. Moreno, J. Odijk, S. Piperidis, and T. Tokunaga, Eds. European Language Resources Association, 1169–1173.

- McCallum, A., and Nigam, K. 1998. A comparison of event models for naive bayes text classification. In AAAI-98 workshop on learning for text categorization, M. Sahami, Eds. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 752(1), 41–48.

- McHugh, M. L. 2012. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia medica, 22(3), 276–282.

- Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., and Dean, J. 2013. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781.

- Mizumoto, A., and Eguchi, M. 2023. Exploring the potential of using an AI language model for automated essay scoring. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 2(2), 100050, 1–13.

- Pranckevičius, T., and Marcinkevičius, V. 2017. Comparison of naive bayes, random forest, decision tree, support vector machines, and logistic regression classifiers for text reviews classification. Baltic Journal of Modern Computing, 5(2), 221–232.

- Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., and Sutskever, I. 2018. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. Technical report, OpenAI. https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf. Accessed: 12-31-2025.

- Razon, A., and Barnden, J. 2015. A new approach to automated text readability classification based on concept indexing with integrated part-of-speech n-gram features. In Proceedings of the international conference recent advances in natural language processing, R. Mitkov, G. Angelova, and K. Bontcheva, Eds. INCOMA, 521–528.

- Rennie, J. D., Shih, L., Teevan, J., and Karger, D. R. 2003. Tackling the poor assumptions of naive bayes text classifiers. In Proceedings of the 20th international conference on machine learning (ICML-03), T. Fawcett, A. Picture, and N. Mishra, Eds. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 616–623.

- Riddle, T., Bhagavatula, S. S., Guo, W., Muresan, S., Cohen, G., Cook, J. E., and Purdie-Vaughns, V. 2015. Mining a written values affirmation intervention to identify the unique linguistic features of stigmatized groups. Proceedings of the 8th Eighth International Conference on Educational Data Mining, O. C. Santos, J. Boticario, C. Romero, M. Pechenizkiy, A. Merceron, P. Mitros, J. M. Luna, M. C. Mihaescu, P. Moreno, A. Hershkovitz, S. Ventura, and M. Desmarais, Eds. International Educational Data Mining Society, 274–281.

- Ruseti, S., Dascalu, M., Johnson, A. M., McNamara, D. S., Balyan, R., McCarthy, K. S., and Trausan-Matu, S. 2018. Scoring summaries using recurrent neural networks. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems: Proceedings of 14th International Conference, R. Nkambou, R. Azevedo, and J. Vassileva, Eds. Springer International Publishing, 191–201.

- Salton, G., and Buckley, C. 1988. Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Information processing & management, 24(5), 513–523.

- Sherman, D. K., Hartson, K. A., Binning, K. R., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Garcia, J., Taborsky-Barba, S., Tomassetti, S., Nussbaum, A. D., and Cohen, G. L. 2013. Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: how self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 591–618.

- Steele, C. M., and Aronson, J. 1995. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811.

- Steele, C. M., and Liu, T. J. 1983. Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 5–19.

- Sun, C., Qiu, X., Xu, Y., and Huang, X. 2019. How to fine-tune BERT for text classification? In China national conference on Chinese computational linguistics. M. Sun, Z. Liu, Y. Liu, X. Huang, and H. Ji, Eds. Springer Cham, 194–206.

- Tang, Y., Tuncel, D., Koerner, C., and Runkler, T. 2025. The few-shot dilemma: Over-prompting large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.13196.

- Tran, N., Pierce, B., Litman, D., Correnti, R., and Matsumura, L. C. 2024. Multi-dimensional performance analysis of large language models for classroom discussion assessment. Journal of Educational Data Mining, 16(2), 304–335.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., and Polosukhin, I. 2017. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 5998–6008.

- Wang, Y., Wang, C., Li, R., and Lin, H. 2022. On the use of BERT for automated essay scoring: Joint learning of multi-scale essay representation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, M. Carpuat, M. de Marneffe, and I. V. M. Ruiz, Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 3416–3425.

- Whitehill, J., and LoCasale-Crouch, J. 2024. Automated evaluation of classroom instructional support with LLMs and BoWs: Connecting global predictions to specific feedback. Journal of Educational Data Mining, 16(1), 34–60.

- Xue, J., Tang, X., and Zheng, L. 2021. A hierarchical BERT-based transfer learning approach for multi-dimensional essay scoring. Ieee Access, 9, 125403–125415.

- Ye, Z., Che, L., Ge, J., Qin, J., and Liu, J. 2024. Integration of multi-level semantics in PTMs with an attention model for question matching. PLoS ONE 19(8): e0305772.

- Yoshida, L. 2024. The impact of example selection in few-shot prompting on automated essay scoring using GPT models. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, A. M. Olney, I. A. Chounta, Z. Liu, O. C. Santos, and I. I. Bittencourt, Eds. Springer Cham, 61–73.

- Zhao, W. X., Zhou, K., Li, J., Tang, T., Wang, X., Hou, Y., Min, Y., Zhang, B., Zhang, J., Dong, Z. and Du, Y. 2023. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223.

- Zhong, R., Ghosh, D., Klein, D., and Steinhardt, J. 2021. Are larger pretrained language models uniformly better? comparing performance at the instance level. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.06020.

- Zhou, C., Sun, C., Liu, Z., and Lau, F. 2015. A C-LSTM neural network for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.08630.

APPENDIX: GPT-4 Prompts

GPT-4 prompt with instructions only:

prompt = [

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are an AI that classifies student text. "

"Return 1 if the student discusses something important, meaningful, positive, or enjoyable to themselves "

"(e.g., using words like 'like,' 'love,' 'favorite,' 'important to me,' 'care about,' or 'enjoy'), "

"or mentions being good at something or recognized for a skill ('good at,' 'best at,' or describing an ability). "

"Return 0 otherwise. Importance must be personal, not about someone else."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": writing_exercise

}

]

GPT-4 prompt without instructions and examples:

prompt = [

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are an AI that classifies student text. "

"Return 1 if the student discusses something important, meaningful, positive, or enjoyable to themselves "

"(e.g., using words like 'like,' 'love,' 'favorite,' 'important to me,' 'care about,' or 'enjoy'), "

"or mentions being good at something or recognized for a skill ('good at,' 'best at,' or describing an ability). "

"Return 0 otherwise. Importance must be personal, not about someone else."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": writing_exercise

}

]

prompt[0]['content'] = prompt[0]['content'] + "\nExamples: " + examples

In our preliminary experiments, the SVM model performed slightly better than the Naive Bayes classifier on our dataset. ↑

Some earlier writing exercises completed on paper by Cohort 1 students were not digitized and were therefore excluded from this analysis, as the students' written essays are not included in the dataset. ↑