Abstract

Generative large language models (LLMs) are widely utilized in education to assist students to learn and instructors to teach. In addition, generative LLMs are used to support personalized learning by recommending learning content in intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs). Nonetheless, there are few studies utilizing generative LLMs in the field of knowledge tracing (KT), which is a key component of ITSs. KT, which uses students' problem-solving histories to estimate their current levels of knowledge, is regarded as a key technology for personalized learning. Nevertheless, most existing KT models are characterized by their development with an ID-based paradigm, which results in a low performance in cold-start scenarios. These limitations can be mitigated by leveraging the vast quantities of external knowledge possessed by generative LLMs. In this study, we propose cold-start mitigation in knowledge tracing by aligning a generative language model as a students’ knowledge tracer (CLST) as a framework that utilizes a generative LLM as a knowledge tracer. Upon collecting data from math, social studies, and science subjects, we framed the KT task as a natural language processing task, wherein problem-solving data are expressed in natural language, and fine-tuned the generative LLM using the formatted KT dataset. Subsequently, we evaluated the performance of the CLST in situations of data scarcity using various baseline models for comparison. The results indicate that the CLST significantly enhanced performance with a dataset of fewer than 100 students in terms of prediction, reliability, and cross-domain generalization.

Keywords

Introduction

As we enter the era of digital transformation, online learning is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. Within this landscape, intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs) have gained substantial importance, offering a range of capabilities—such as personalized feedback, adaptive learning pathways, and early identification of at-risk students—that collectively enhance the learning experience (Abdelrahman et al., 2023; Colpo et al., 2024; Emerson et al., 2023; Wang and Mousavi, 2023).

Among the various technologies used in ITSs, knowledge tracing (KT) has emerged as a key component that enables personalized learning (Shen et al., 2021). KT aims to predict whether a student will answer a given exercise correctly by analyzing their prior performance on related knowledge components (KCs), using it as a proxy for their current understanding (Wu and Ling, 2023). Understanding the student’s knowledge states helps in recommending appropriate learning materials and offering relevant feedback, thereby enhancing learning outcomes.

A variety of KT models have been proposed to meet these expectations, including both traditional and deep learning (DL)-based models (Abdelrahman et al., 2023). In particular, the performance of DL-based KT models in terms of predicting knowledge states has notably improved with successive developments.

The majority of existing KT models follow an ID-based paradigm, where students, exercises, or knowledge components (KCs) are represented using unique ID embeddings. While this approach is effective in many settings, they tend to perform poorly in cold-start situations, where little or no prior interaction data is available for new users or items (Zhao et al., 2020).

The cold-start problem refers to a decline in the performance of personalized systems caused by insufficient user-item interaction data (Weng et al., 2008). It is typically categorized into three types: user cold-start, which arises when new users enter the system; item cold-start, when new items are introduced; and system cold-start, where both users and items are new and lack prior interactions (Idrissi et al., 2019; Sethi & Mehrotra, 2021; Tey et al., 2021). The system cold-start scenario is particularly challenging because no interaction history exists for either entity. This situation is common when educational institutions or EdTech companies first adopt KT models to develop intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs). In such cases, a lack of sufficient problem-solving data from students and metadata from exercises severely hampers the performance of conventional KT models. As a result, mitigating the system cold-start problem is a critical step toward successfully deploying KT-based personalized learning platforms in real-world educational settings.

As an issue stemming from scarce data on users or items in recommendation systems (Sahebi and Cohen, 2011), the cold-start problem is regarded as an important issue in the KT field (Wu et al., 2022). Many studies have made efforts to alleviate the cold-start issue inherent to KT, primarily by utilizing various types of side information such as the language proficiency of students (Jung et al., 2023), difficulty level of questions (Liu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021), and students' question-answering patterns (Xu et al., 2023). However, these methods require effort to obtain additional information beyond each student’s problem-solving history, which may be difficult in the early stages of a service.

On the other hand, generative large language models (LLMs) demonstrate outstanding performance in a wide range of fields and downstream applications (Jin et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2023a). Generative LLMs, such as GPT, are auto-regressive language models that can generate text similar to human writing. These models contain large quantities of external knowledge and are able to extract high-quality textual features.

The development of KT models using external knowledge inherently possessed by generative LLMs opens the possibility of improving performance in cold-start situations as well as enhancing the domain adaptability of KT models. In a cold-start scenario, the scarcity of information from the target domain can be supplemented by using information from other domains as training data (Cheng et al., 2022). However, domain adaptation is challenging because most ID-based KT models currently in use are domain-specific.

Despite the potential benefits of using generative LLMs in the KT field, little research has been conducted on their applicability to KT tasks. One such study was conducted (Neshaei et al., 2024); however, this attempt failed to fully utilize the strengths of generative LLMs, only expressing exercise description information through IDs. Furthermore, their model relied solely on the number of correct and incorrect answers submitted by each student, whereas it is also important to account for the order in which each student solves problems (Pandey and Karypis, 2019). As such, research on modeling KT through language processing remains insufficient. Given their capabilities, generative LLMs can be deployed to overcome the limitations of the ID-based paradigm. As a result, more research is needed to determine the efficacy of expressing KT in natural language using generative LLMs.

In this study, we propose a framework called “Cold-start mitigation in KT by aligning a generative language model as a students’ knowledge tracer (CLST).” Unlike existing ID-based methods, CLST describes exercises using natural language descriptions (e.g., names of KCs). We conducted experiments to determine whether a generative LLM aligned with KT could perform well in system cold-start scenarios with a small number of users and few problem-solving histories per user. Initially, we collected data for a variety of subjects, including mathematics, social studies, and science. The KT task was then framed as a natural language processing (NLP) task by expressing problem-solving data —comprising the exercise descriptions and student responses— in natural language, and the formatted KT dataset was used to fine-tune the generative LLM. Finally, multiple experiments were conducted to investigate CLST's performance in cold-start situations. This study was conducted to address the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: In cold-start scenarios, does the proposed method demonstrate successful prediction performance?

RQ2: How can exercises be effectively represented in natural language?

RQ3: Does the proposed model provide a convincing prediction of students’ knowledge states?

RQ4: Is the proposed model effective at predicting student knowledge in cross-domain scenarios?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: A literature review on KT and generative LLMs in personalized learning are presented in Section 2. Section 3 describes the methodology developed in this study. Section 4 presents and discusses the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study.

Related works

Knowledge tracing

KT utilizes students' problem-solving histories to approximate their current knowledge states and subsequently predict their future responses. A student’s problem-solving history can be represented as , where corresponds to an exercise that has been solved at a specific time , and represents the correctness of the student’s response to .

Figure 1 depicts the overall process and results of the KT task. Each exercise is labeled with the associated KCs. For example, exercise is related to , and exercise is related to . In a student's problem-solving histories, there is a record of whether the student answered exercises related to specific KCs correctly or incorrectly. Based on this information, the goal of the KT is to predict whether the student will answer a new exercise related to a specific KC correctly when it is presented to them. Additionally, by analyzing the student's problem-solving results over time, we can predict the mastery level for each KC and ultimately estimate the student's current knowledge state. The estimated knowledge state can be visualized in various ways; one such method is representing it using a radar chart, as shown on the right side of Figure 1.

KT models can be distinctly classified as traditional or DL-based (Abdelrahman et al., 2023). Traditional approaches of KT include Bayesian knowledge tracing (BKT) and factor analysis models. BKT (Corbett and Anderson, 1994) is a Markov-process-based approach that represents each student’s knowledge state as a collection of binary values, whereas factor analysis approaches analyze the factors that affect students’ knowledge states, such as attempt counts and exercise difficulty. Item Response Theory (IRT; Van der Linden and Hambleton, 1997) and Performance factor analysis (PFA; Pavlik et al., 2009) are representative works on factor analysis.

The growth of online education has led to a substantial accumulation of problem-solving data, allowing DL-based KT models to reach outstanding performance. Such methods include recurrent neural network (RNN)-based (Delianidi and Diamantaras, 2023; Piech et al., 2015; Yeung and Yeung, 2018), memory-augmented neural network (MANN)-based (Abdelrahman and Wang, 2019; Kim et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2017), transformer-based (Ghosh et al., 2020; Pandey and Karypis, 2019; Yin et al., 2023), and graph neural network (GNN)-based (Nakagawa et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2024) models. In this study, the BKT (Corbett and Anderson, 1994) and factor analysis models (Pavlik et al., 2009; Van der Linden and Hambleton, 1997) were chosen from the traditional KT models, and the RNN-based model (Piech et al., 2015), MANN-based model (Zhang et al., 2017), and transformer-based model (Ghosh et al., 2020) were chosen as baseline models and used in the experiment.

Generative LLMs in education

LLMs are pre-trained auto-regressive language models, such as GPT-3, capable of generating human-like text (Peng et al., 2023). These probabilistic models serve as the foundation for natural language processing (NLP) techniques, which enable the processing of natural language using algorithms. The term ‘large’ denotes the extensive number of parameters each of these models contains, while the term ‘generative’ refers to a subset of LLMs designed for text generation. Generative LLMs are now at the core of a variety of applications, including summarization and translation, generally delivered through dialogue-like communication with the user (Zhao et al., 2023).

In light of their massive potential, attempts are being made to utilize LLMs in the field of education. First, studies have been conducted to analyze the effectiveness of generative LLMs in assisting learning. Generative LLMs can provide immediate feedback on errors that students may make during the learning process. Experimental results from many studies have shown that generative LLMs have great potential in tasks such as grammar error correction (Fan et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023) and programming error correction (Do Viet and Markov, 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). Additionally, generative LLMs show promise in tasks focused on generating hints that support students in solving problems independently, as opposed to offering direct problem-solving feedback (Pardos and Bhandari, 2023). Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that feedback generated by LLMs can be effective in supporting student learning, across domains such as mathematics, programming, and open-ended academic writing tasks (Dai et al., 2023; Dai et al., 2024; Pardos and Bhandari, 2024).

Research on how generative LLMs can assist teachers in the teaching process has also been actively conducted. According to many studies, generative LLMs have been found to successfully generate questions for reading comprehension (Bulut and Yildirim-Erbasli, 2022), math word problems (Zhou et al., 2023b), and computer programming tasks (Doughty et al., 2024). Additionally, studies have been carried out on adaptive curriculum design (Sridhar et al., 2023), automatic grading (Malik et al., 2019; Whitehill and LoCasale-Crouch, 2023), and automated feedback generation for assignments (Abdelghani et al., 2024) utilizing generative LLMs.

Meanwhile, studies have also been conducted on utilizing generative LLMs to support personalized learning. In this regard, research has explored methods for generating learning paths based on students' knowledge diagnosis results (Kuo et al., 2023), as well as generating explanations for learning recommendations (Abu-Rasheed et al., 2024).

Although several studies have been conducted on the use of generative LLMs in personalized learning, few attempts have been made to apply them to the KT field, which is a core technology to support personalized learning. Ni et al. (2024) employed generative LLMs to enhance item representations; however, they did not fully leverage the models’ instruction-following capabilities. In contrast, Neshaei et al. (2024) utilized instruction-following but represented exercises only as IDs, preventing the model from using information contained in the item content (e.g., problem text). Moreover, the sequence of problem-solving by students is crucial in the KT task, whereas the study in question only considered the number of correct and incorrect answers by each student. In other words, there is still plenty of potential for further research on the effectiveness of generative-LLM-based KT models.

In this study, we examined the efficacy of aligning generative LLMs to KT by expressing the KT task in natural language. The CLST proposed in this study markedly differs from the research by Neshaei et al. (2024) in that it describes exercises using natural language descriptions (e.g., names of KCs) and reflects the sequence of problem-solving. Accordingly, there are differences in the prompt templates used to fine-tune the LLM. Figures A1 and A2 in Appendix A show examples of prompt templates from the two studies (Section 6.1).

Methodology

Problem formulation

Letting be a set of exercises, a student's responses to exercises in , and records of one's problem-solving can be represented as the set , comprising tuples . Here, represents the exercise solved at a specific time step , and represents the correctness of the answer recorded by the student at . With this notation, we can formulate the KT task in the following way: Given a student’s historical information , KT aims to predict the probability of correctly solving a new exercise at . In the following equation, denotes the KT model.

CLST: Cold-start mitigation in KT by aligning a generative language model as a students’ knowledge tracer

KTLP formatting: Utilizing natural language as KT information carrier

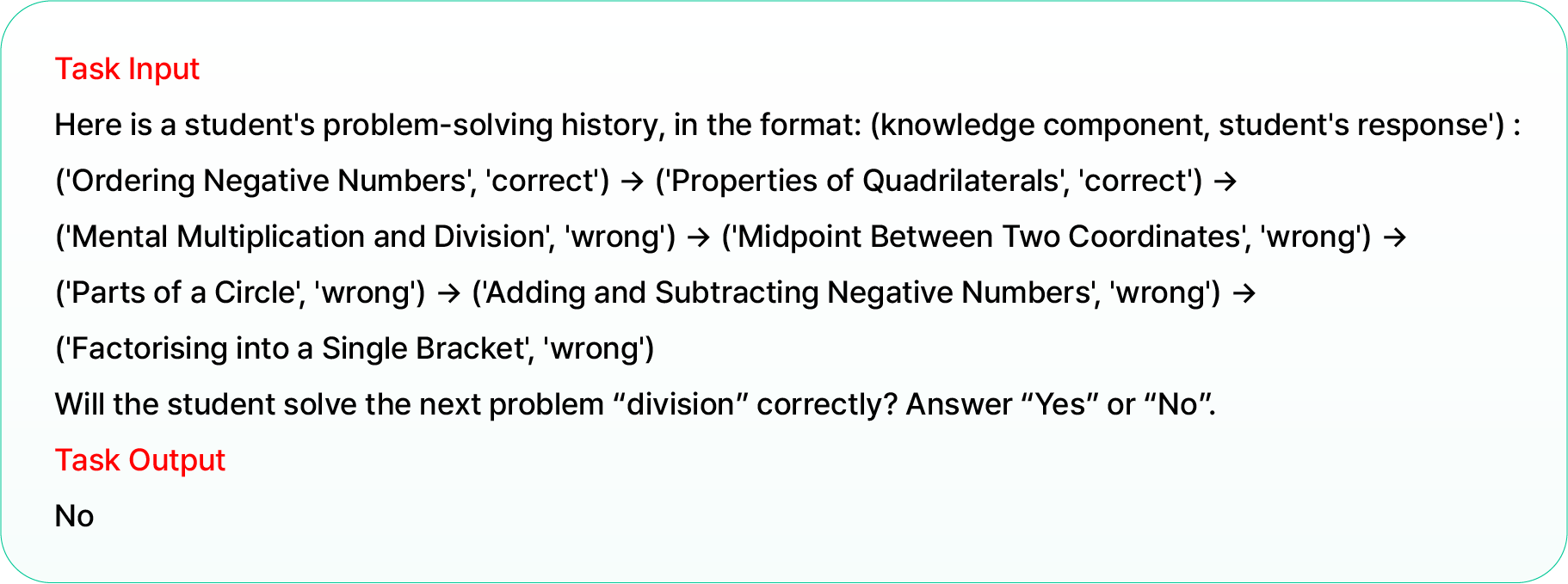

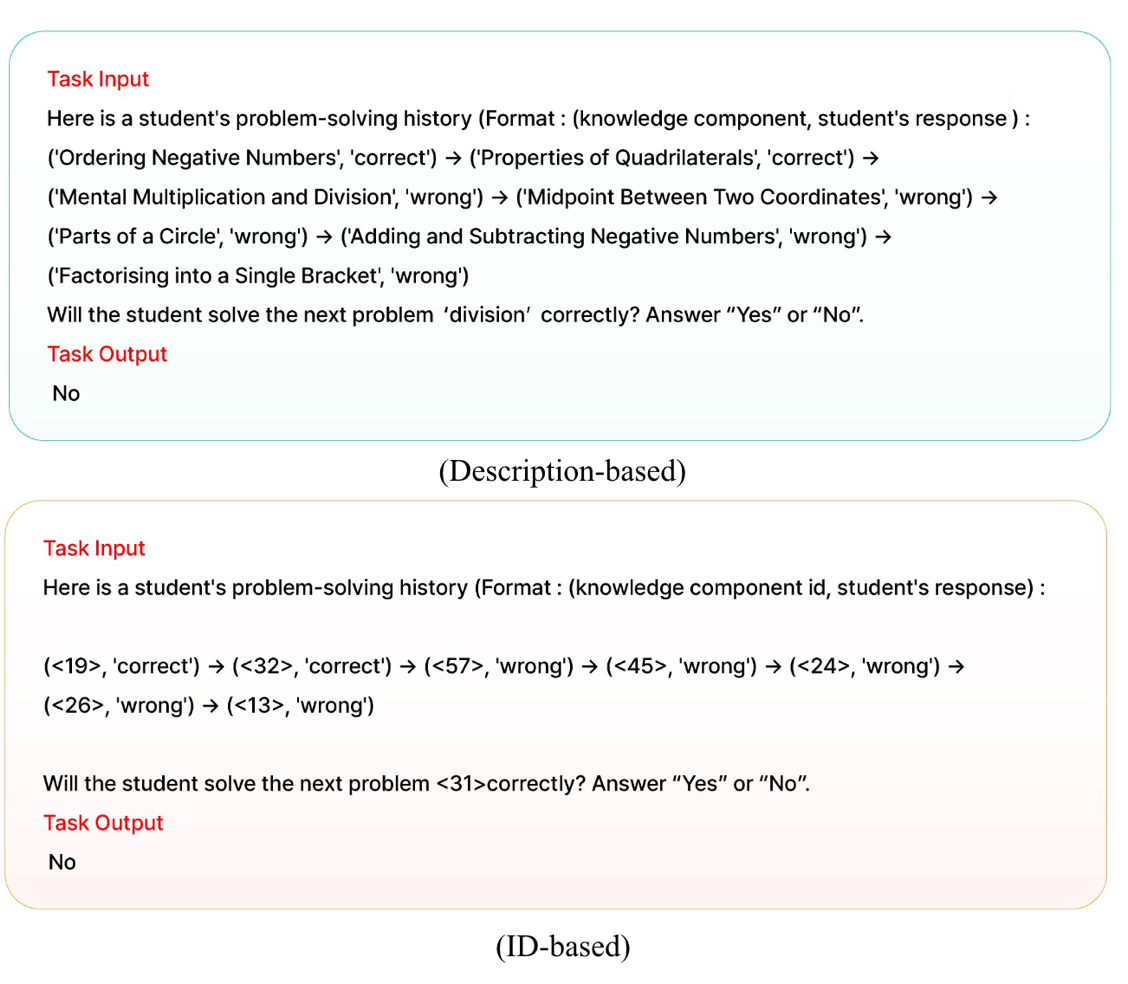

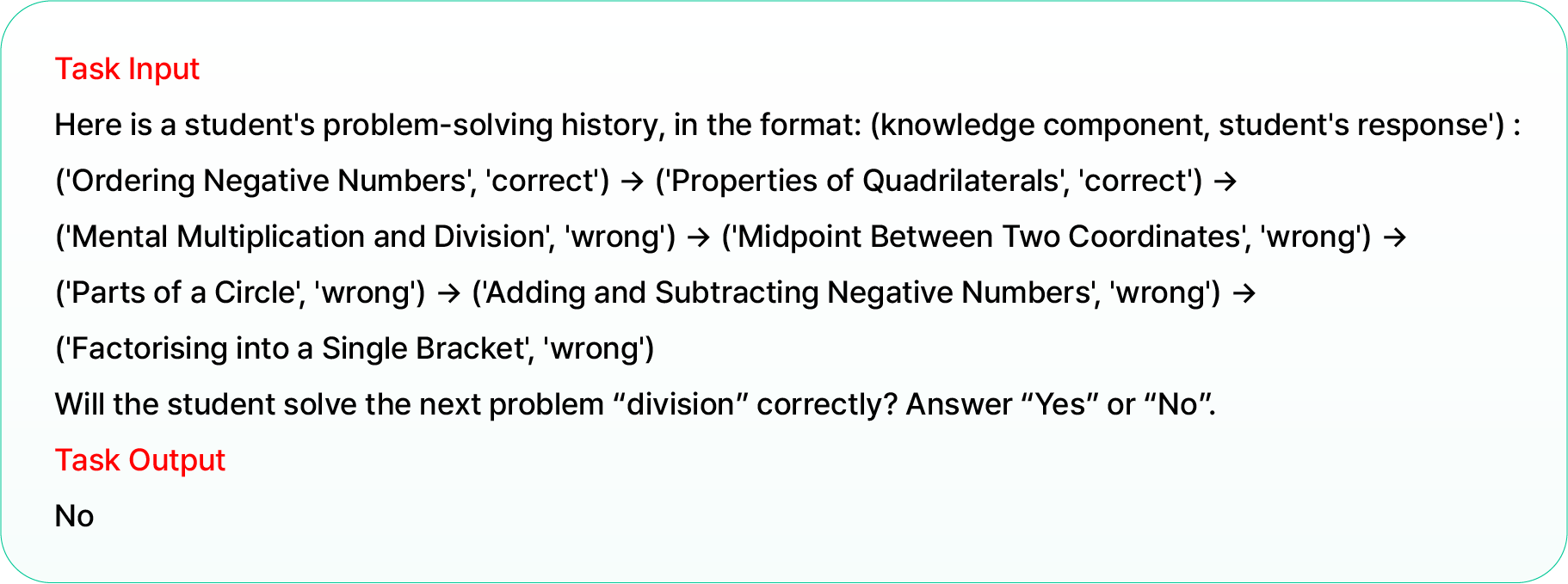

A student’s problem-solving history X must be transformed into textual sequences using prompt templates for generative LLMs. We start by organizing ‘Task Input’ to instruct the model to determine whether the student will solve the target exercise based on their historical interactions, and then output a binary response of “Yes” or “No”. Here, each exercise is represented by a textual description (e.g., name of KC), with interactions represented as tuples of (exercise description, correctness), connected by the ‘’ symbol (see Figure 2).

Additionally, the binary label is converted into a binary key answer word

to organize the ‘Task Output’. The aforementioned process allows us to frame the KT task as a language processing task. We call this process knowledge tracing as language processing (KTLP) formatting, which can be formulated as follows:

Here, denotes the KTLP formatting function. Figure 2 depicts a sample KTLP-formatted interaction.

Response prediction with CLST

Upon taking the discrete tokens of as input, an LLM is used to generate the next token as the output. This process can be formulated as follows:

where denotes the LLM, denotes the vocabulary size, and denotes the next predicted token drawn from the probability distribution .

However, the KT model’s output should be a floating-point number rather than a discrete token . Therefore, following prior studies on point-wise scoring tasks (e.g., recommendation), we take the logits and apply a bi-dimensional softmax over the logits of binary answer words. The KT prediction of LLM can thus be written as:

Instruction fine-tuning using KTLP-formatted data with LoRA architecture

Since we generated both the task input and the task output in natural language, we can optimize the LLM by following the common instruction fine-tuning and causal language modeling paradigm. This process can be formulated as follows:

Here, and denote the KTLP-formatted input and output, respectively, denotes the training dataset, represents the -th token of , denotes the token preceding , and represents the parameters of .

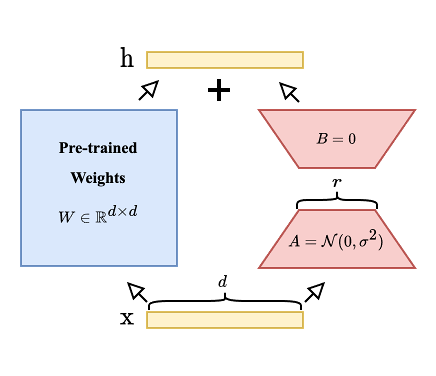

However, it is highly resource-intensive to fine-tune every parameter of an LLM. To utilize training resources efficiently, we instead adopted low-rank adaptation (LoRA) (Hu et al., 2022). Figure 3 depicts how fine-tuning of the LoRA method works. For each target layer with pre-trained weight (W), the weight is frozen and the update is restricted to a low-rank form , where , , and . Given an input , the forward pass becomes as follows: (h=Wx+BAx).

As a result, the original parameters can be preserved in a frozen state while additional information in the fine-tuning dataset is efficiently incorporated by training smaller matrices. The final fine-tuning process can be formulated as follows:

Here, represents the collection of LoRA matrices , which are only updated during the fine-tuning process.

Dataset

To investigate the effectiveness of CLST, we collected data pertaining to mathematics, social studies, and science subjects. Table 1 lists detailed statistics for each dataset.

NIPS34 | Algebra05 | Assist09 | Social studies | Science | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

# interactions | 1,382,727 | 607,014 | 282,071 | 4,215,373 | 5,484,647 |

# students | 4,918 | 571 | 3,644 | 40,217 | 45,211 |

# exercises | 948 | 173,113 | 17,727 | 14,168 | 29,795 |

# KCs | 57 | 112 | 123 | 40 | 36 |

Median interactions per student | 239 | 580 | 25 | 40 | 35 |

Median KCs per student | 26 | 54 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

For mathematics data, we selected the open benchmark datasets NIPS34, Algebra05, and Assistments09 (Assist09), which are used as standard benchmarks for KT methods (Sun et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2023). The NIPS34 dataset was sourced from the third and fourth tasks of the NeurIPS 2020 Education Challenge. Gathered from the Eedi platform, the data encompass students’ problem-solving histories for multiple-choice math exercises (Wang et al., 2020). The Algebra05 dataset was sourced from the EDM challenge of the 2010 KDD Cup, comprising the responses of 13 to 14 year old students to algebra exercises (Stamper et al., 2010). The Assist09 dataset contains student response data on math exercises collected from the ASSISTments platform in 2009–2010 (Feng et al., 2009).

For social studies and science, we gathered data from Classting AI Learning, an online education platform that offers learning materials in a range of academic subjects for K–12 students.

Baseline models

In our comparative experiments, traditional, DL-based, and LLM-based KT models were selected as baselines.

As traditional KT models, we selected the BKT, item response theory (IRT), and PFA models. BKT is a hidden Markov model that encodes students' knowledge states with binary variables (Corbett and Anderson, 1994). IRT models KT via logistic regression, accounting for each student’s ability as well as the difficulty of each exercise (Van der Linden and Hambleton, 1997). PFA is another logistic regression model that incorporates exercise difficulty alongside each student’s prior successes and failures (Pavlik et al., 2009).

As DL-based KT models, we selected deep knowledge tracing (DKT), dynamic key-value memory networks for knowledge tracing (DKVMN), and attentive knowledge tracing (AKT). DKT (Piech et al., 2015) is a standard RNN-based KT model that predicts students’ knowledge states with a single LSTM layer (Shen et al., 2024). DKVMN (Zhang et al., 2017) is a KT model that uses static memory to encode latent KCs and dynamic memory to track student proficiency for the latent KCs (Shen et al., 2024). AKT (Ghosh et al., 2020) is an attention-mechanism-based KT model that improves predictive performance by incorporating context-aware attention with Rasch model-based encoding.

The LLM-based KT model proposed in (Neshaei et al., 2024) was also chosen as a baseline model. To ensure a fair comparison, the model by Neshaei et al. (2024) was implemented using mistral-7b-instruct-v02, the same model employed in the CLST implementation, and subsequently used in the experiment.

Additionally, we implemented NLP-enhanced DL-based KT models. These models initialize exercise embedding vectors in DL-based KT models with encoded text features of the KC name that corresponds to each exercise. which covers each exercise. Specifically, we used OpenAI[1]’s text-embedding-3-large to encode text features, with the resulting KT models denoted as , , and .

In addition, we added BKT and DKT with one global KC as baseline models. This is to understand whether the CLST is simply good at capturing overall evolution in student ability, or is actually capturing some deeper phenomenon.

experimental settings

To guarantee the quality of the data, only interactions from students who responded to more than five exercises were used.

The objective of this study was to mitigate problems that arise from system cold-start situations. Accordingly, we randomly selected training sets comprised of a limited number of 64, 32, 16, and 8 students. Also, we only considered the first 50 interactions per student in the experiment (Wang et al., 2021).

For the mathematics data, 20% of the students were held out for the test set. For the social studies and science data, we selected 1,000 random students as the test set for each subject.

We executed each method five times with different random seeds and reported the average outcomes. We generated five different random splits of training and testing students, then evaluate the model one time on each split.

The selection of a base model requires careful consideration. Among existing generative LLMs, many do not provide accessibility to their model weights or APIs. Furthermore, data security is a critical concern in the field of education, necessitating additional discussion about the use of third-party APIs (e.g., OpenAI). After careful consideration, we selected the instruction-tuned Mistral-7B[2] (Jiang et al., 2023). For other baseline hyperparameters, we adhered to the settings described by Lee et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2021), as their evaluation protocols were similar to our own.

All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU and Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4210R CPU @ 2.40GHz CPU.

Results and discussion

To evaluate the effectiveness of CLST from multiple perspectives, as well as address the four RQs, we conducted four experiments with the following objectives: 1) compare predictive performance between CLST and the baseline models in cold-start scenarios; 2) investigate the effectiveness of each component of the CLST through an ablation study; 3) analyze learning trajectories using CLST; and 4) compare predictive performance between CLST and the baseline models in cross-domain tasks. The following subsections discuss our experimental results.

Predictive performance under cold-start scenarios

We evaluated the predictive performance of CLST in cold-start scenarios involving a limited number of students, with the training set sequentially reduced from 64 to 8 students. All baseline models listed in Section 3.4 were chosen for comparison in this experiment. We measured the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) as an evaluation metric. AUC is the most widely used indicator for evaluating KT performance, with higher scores indicating better performance (Liu et al., 2022).

Tables 2 through 6 present detailed quantitative results of the cold-start experiments, where the best AUC score for each trial is bolded and underlined, while the second-highest AUC score is underlined. Confidence intervals (CI) are also provided for each experimental outcome.

Dataset | #Students | Average AUC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional | DL-based | NLP-enhanced | Global KC | LLM-based | ||||||||||

BKT | IRT | PFA | DKT | DKVMN | AKT | DKT _text | DKVMN_text | AKT _text | BKT | DKT | Neshaei et al | CLST | ||

NIPS34 | 8 | 0.544 ±0.009 | 0.540 ±0.003 | 0.420 ±0.017 | 0.540 ±0.010 | 0.555 ±0.007 | 0.558 ±0.014 | 0.570 ±0.015 | 0.581 ±0.012 | 0.578 ±0.014 | 0.635 ±0.040 | 0.490 ±0.015 | 0.568 ±0.014 | 0.635 ±0.006 |

16 | 0.562 ±0.007 | 0.565 ±0.003 | 0.501 ±0.049 | 0.560 ±0.017 | 0.590 ±0.005 | 0.583 ±0.006 | 0.594 ±0.014 | 0.601 ±0.012 | 0.608 ±0.014 | 0.629 ±0.032 | 0.542 ±0.014 | 0.564 ±0.020 | 0.637 ±0.012 | |

32 | 0.574 ±0.006 | 0.586 ±0.005 | 0.589 ±0.030 | 0.581 ±0.015 | 0.619 ±0.006 | 0.605 ±0.013 | 0.626 ±0.013 | 0.629 ±0.012 | 0.639 ±0.005 | 0.641 ±0.028 | 0.588 ±0.013 | 0.592 ±0.015 | 0.651 ±0.010 | |

64 | 0.584 ±0.007 | 0.607 ±0.002 | 0.645 ±0.013 | 0.595 ±0.013 | 0.637 ±0.005 | 0.620 ±0.011 | 0.639 ±0.010 | 0.642 ±0.013 | 0.644 ±0.010 | 0.646 ±0.026 | 0.638 ±0.010 | 0.640 ±0.004 | 0.661 ±0.009 | |

Dataset | #Students | Average AUC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional | DL-based | NLP-enhanced | Global KC | LLM-based | ||||||||||

BKT | IRT | PFA | DKT | DKVMN | AKT | DKT _text | DKVMN_text | AKT _text | BKT | DKT | Neshaei et al | CLST | ||

Algebra05 | 8 | 0.620 ±0.023 | 0.519 ±0.008 | 0.475 ±0.033 | 0.630 ±0.027 | 0.629 ±0.016 | 0.601 ±0.024 | 0.617 ±0.026 | 0.629 ±0.013 | 0.624 ±0.026 | 0.610 ±0.026 | 0.626 ±0.026 | 0.572 ±0.060 | 0.655 ±0.015 |

16 | 0.625 ±0.020 | 0.539 ±0.008 | 0.513 ±0.036 | 0.641 ±0.026 | 0.637 ±0.019 | 0.611 ±0.014 | 0.628 ±0.019 | 0.647 ±0.014 | 0.641 ±0.013 | 0.609 ±0.022 | 0.625 ±0.019 | 0.617 ±0.041 | 0.661 ±0.020 | |

32 | 0.670 ±0.008 | 0.560 ±0.005 | 0.555 ±0.023 | 0.656 ±0.022 | 0.659 ±0.011 | 0.647 ±0.014 | 0.664 ±0.018 | 0.674 ±0.007 | 0.668 ±0.010 | 0.634 ±0.005 | 0.628 ±0.018 | 0.681 ±0.006 | 0.702 ±0.008 | |

64 | 0.676 ±0.006 | 0.586 ±0.005 | 0.597 ±0.012 | 0.684 ±0.027 | 0.676 ±0.008 | 0.667 ±0.005 | 0.695 ±0.002 | 0.677 ±0.008 | 0.679 ±0.005 | 0.635 ±0.003 | 0.631 ±0.002 | 0.669 ±0.016 | 0.722 ±0.004 | |

Dataset | #Students | Average AUC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional | DL-based | NLP-enhanced | Global KC | LLM-based | ||||||||||

BKT | IRT | PFA | DKT | DKVMN | AKT | DKT _text | DKVMN_text | AKT _text | BKT | DKT | Neshaei et al | CLST | ||

Assist09 | 8 | 0.550 ±0.011 | 0.506 ±0.002 | 0.479 ±0.018 | 0.553 ±0.019 | 0.545 ±0.013 | 0.539 ±0.013 | 0.555 ±0.014 | 0.577 ±0.014 | 0.616 ±0.022 | 0.640 ±0.018 | 0.508 ±0.014 | 0.653 ±0.017 | 0.689 ±0.003 |

16 | 0.595 ±0.011 | 0.509 ±0.003 | 0.482 ±0.017 | 0.583 ±0.018 | 0.562 ±0.015 | 0.558 ±0.012 | 0.570 ±0.011 | 0.588 ±0.010 | 0.633 ±0.029 | 0.659 ±0.021 | 0.608 ±0.011 | 0.606 ± 0.075 | 0.682 ±0.017 | |

32 | 0.606 ±0.021 | 0.514 ±0.003 | 0.497 ±0.030 | 0.609 ±0.017 | 0.586 ±0.018 | 0.571 ±0.024 | 0.596 ±0.028 | 0.611 ±0.017 | 0.657 ±0.011 | 0.644 ±0.021 | 0.601 ±0.028 | 0.683 ±0.010 | 0.684 ±0.029 | |

64 | 0.638 ±0.004 | 0.525 ±0.003 | 0.570 ±0.019 | 0.654 ±0.008 | 0.633 ±0.007 | 0.606 ±0.011 | 0.638 ±0.004 | 0.633 ±0.007 | 0.676 ±0.009 | 0.660 ±0.008 | 0.665 ±0.004 | 0.684 ±0.010 | 0.711 ±0.007 | |

Dataset | # Students | Average AUC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional | DL-based | NLP-enhanced | Global KC | LLM-based | ||||||||||

BKT | IRT | PFA | DKT | DKVMN | AKT | DKT _text | DKVMN_text | AKT _text | BKT | DKT | Neshaei et al | CLST | ||

Science | 8 | 0.515 ±0.004 | 0.501 ±0.001 | 0.492 ±0.008 | 0.510 ±0.004 | 0.518 ±0.005 | 0.512 ±0.006 | 0.518 ±0.003 | 0.512 ±0.005 | 0.510 ±0.005 | 0.516 ±0.008 | 0.452 ±0.003 | 0.539 ±0.026 | 0.579 ±0.012 |

16 | 0.523 ±0.008 | 0.504 ±0.004 | 0.482 ±0.009 | 0.519 ±0.007 | 0.517 ±0.006 | 0.519 ±0.005 | 0.518 ±0.005 | 0.520 ±0.011 | 0.522 ±0.012 | 0.529 ±0.005 | 0.500 ±0.005 | 0.535 ±0.020 | 0.580 ±0.018 | |

32 | 0.539 ±0.007 | 0.510 ±0.003 | 0.494 ±0.016 | 0.534 ±0.007 | 0.528 ±0.006 | 0.526 ±0.004 | 0.529 ±0.004 | 0.544 ±0.009 | 0.552 ±0.008 | 0.544 ±0.006 | 0.530 ±0.004 | 0.535 ±0.026 | 0.587 ±0.011 | |

64 | 0.558 ±0.004 | 0.520 ±0.004 | 0.525 ±0.014 | 0.544 ±0.004 | 0.540 ±0.004 | 0.540 ±0.007 | 0.538 ±0.006 | 0.549 ±0.003 | 0.571 ±0.005 | 0.561 ±0.003 | 0.572 ±0.006 | 0.531 ±0.067 | 0.604 ±0.008 | |

Dataset | # Students | Average AUC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional | DL-based | NLP-enhanced | Global KC | LLM-based | ||||||||||

BKT | IRT | PFA | DKT | DKVMN | AKT | DKT _text | DKVMN_text | AKT _text | BKT | DKT | Neshaei et al | CLST | ||

Social Studies | 8 | 0.524 ±0.006 | 0.504 ±0.001 | 0.476 ±0.015 | 0.514 ±0.010 | 0.512 ±0.005 | 0.518 ±0.007 | 0.521 ±0.009 | 0.527 ±0.009 | 0.522 ±0.009 | 0.528 ±0.005 | 0.478 ±0.009 | 0.497 ±0.027 | 0.574 ±0.009 |

16 | 0.539 ±0.007 | 0.508 ±0.002 | 0.492 ±0.007 | 0.532 ±0.003 | 0.523 ±0.007 | 0.525 ±0.004 | 0.537 ±0.006 | 0.542 ±0.008 | 0.546 ±0.013 | 0.542 ±0.005 | 0.501 ±0.006 | 0.507 ±0.021 | 0.557 ±0.010 | |

32 | 0.549 ±0.009 | 0.511 ±0.001 | 0.500 ±0.008 | 0.525 ±0.010 | 0.523 ±0.012 | 0.524 ±0.005 | 0.535 ±0.011 | 0.552 ±0.012 | 0.556 ±0.009 | 0.553 ±0.008 | 0.515 ±0.011 | 0.522 ±0.026 | 0.571 ±0.013 | |

64 | 0.563 ±0.009 | 0.519 ±0.002 | 0.553 ±0.008 | 0.549 ±0.006 | 0.544 ±0.006 | 0.539 ±0.004 | 0.563 ±0.003 | 0.565 ±0.009 | 0.581 ±0.006 | 0.567 ±0.007 | 0.569 ±0.003 | 0.580 ±0.014 | 0.596 ±0.008 | |

As described in the Tables, CLST outperformed every baseline model, irrespective of the size of the training set. Furthermore, models utilizing NLP demonstrated superior overall performance in comparison to traditional and DL-based methods. CLST outperformed the second-best model by up to 24.52%, 14.66%, 12.31%, and 8.71% for a training set containing 8, 16, 32, and 64 students, respectively. Furthermore, when comparing performance between CLST and the baseline models across different datasets, CLST exhibited improvements of up to 13.69% on the NIPS34 dataset, 5.62% on the Algebra05 dataset, 24.52% on the Assist09 dataset, 11.82% on the Classting Science dataset, and 9.62% on the Classting Social Studies dataset.

Most existing KT models represent exercises with their distinctive identity values, or IDs. In our experiments, the models representing exercises using textual descriptions generally outperformed those using ID-based representations. In particular, the proposed CLST, which expresses all information in natural language, exhibited the highest performance in each cold-start scenario. We speculate that CLST's strong performance stems from its use of natural language representations, which allow LLMs to better leverage underlying knowledges.

We can therefore provide the following response to RQ1 (In cold-start scenarios, does the proposed method demonstrate successful prediction performance?): in all datasets and all cold-start scenarios, the proposed method outperformed the baseline KT models, suggesting that it can help mitigate the cold-start problem in KT.

The cold-start problem has been a major concern in the field of KT (Wu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2020). Previous studies have suggested methods that utilize additional information from the exercise side (e.g., relations among KCs) or the student side (e.g., language proficiency) to address this issue (Jung et al., 2023). However, these methods require effort to acquire additional information that extends beyond each student’s problem-solving history, which may be difficult to collect during the initial stages of service. In contrast, we suggest a novel approach to mitigating the cold-start issue by conceptualizing KT as language processing and leveraging the capabilities of generative LLMs.

Empirical measurement of fine-tuning and inference cost

The average training step duration was measured to be approximately 4 seconds with a batch size of 4. As an example, fine-tuning on the Algebra05 dataset (21k samples) with an accumulation step size of 4 took about 6.8 hours on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU. The empirical peak GPU memory usage during training was around 19 GB, and inference required up to about 16 GB. Based on a typical GPU power draw of approximately 250 W under training load, the estimated energy consumption for this session was about 1.7 kWh.

Note that total training time, memory usage, and power consumption may vary depending on the dataset size, batch size, and accumulation settings.

Ablation study

To investigate the effectiveness of each component of CLST in addressing the cold-start issue, we conducted several experiments with the following objectives: (1) comparison of performance with respect to exercise representations (2) to evaluate the effectiveness of fine-tuning.

Comparison of performance with respect to exercise representations

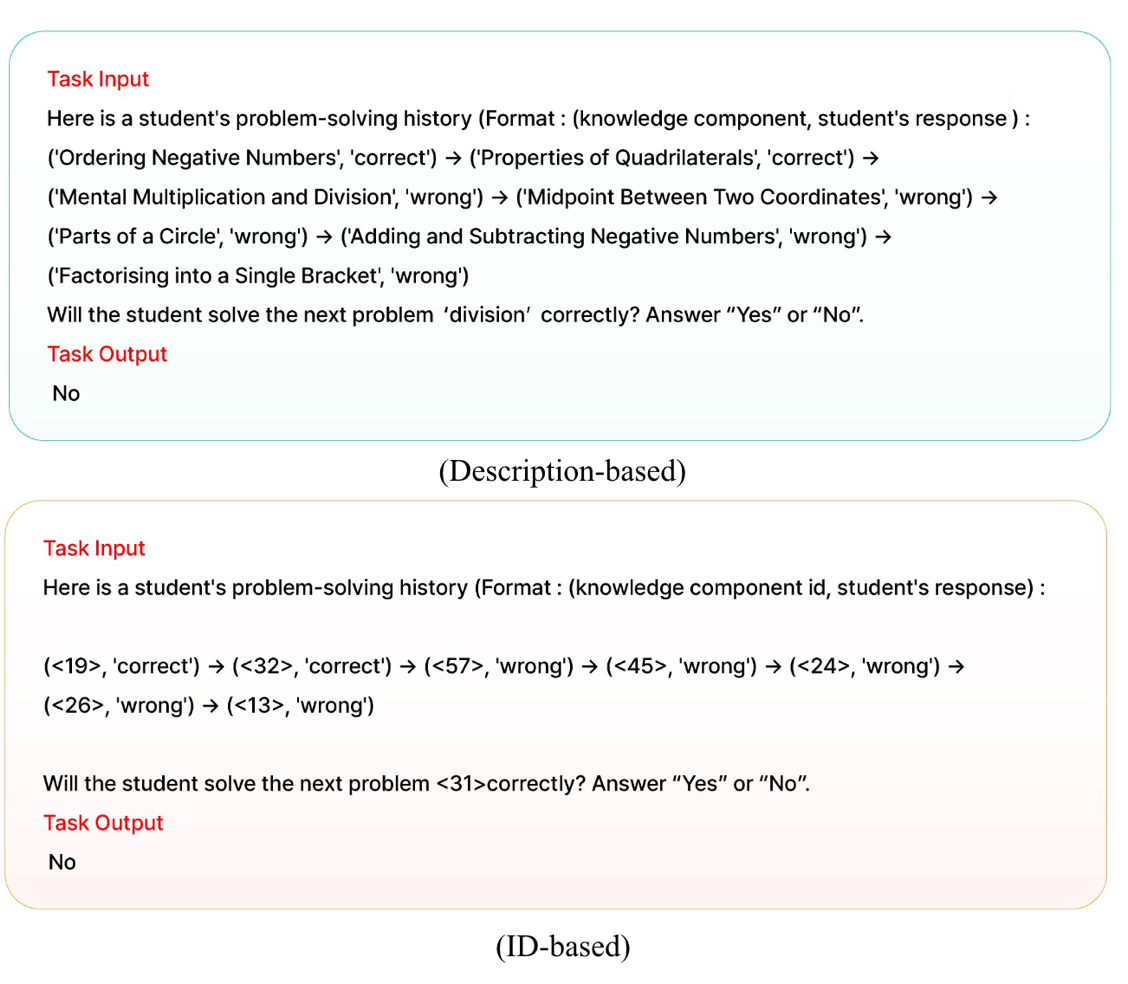

We conducted additional experiments to compare two ways of representing exercises in KTLP format: a description-based method that represents each exercise with the corresponding KC name, which is used in CLST, and the conventional ID-based approach, wherein the ID of the corresponding KC is used to represent each exercise. In this method, the ID of each KC is defined using brackets in the format `<ID>' and added as extra vocabulary. Figure 4 presents sample representations of an exercise using both approaches.

Table 7 presents a comparison of predictive performance with respect to exercise representation. The skill ID and skill name of each exercise are accessible in all datasets utilized in the experiment. The method of directly expressing the skill ID using LLM was referred to as "ID-based" for each dataset, while the method of expressing the skill name in natural language was referred to as "description-based." In most cases, the description-based method was observed to outperform the ID-based method.

Dataset | Method | # Students | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | ||

NIPS34 | ID-based | 0.658 | 0.646 | 0.638 | 0.629 |

Description-based | 0.661 | 0.651 | 0.637 | 0.635 | |

Algebra05 | ID-based | 0.659 | 0.631 | 0.548 | 0.584 |

Description-based | 0.722 | 0.702 | 0.661 | 0.655 | |

Assist09 | ID-based | 0.691 | 0.661 | 0.661 | 0.668 |

Description-based | 0.711 | 0.684 | 0.682 | 0.689 | |

Social Studies | ID-based | 0.600 | 0.541 | 0.537 | 0.567 |

Description-based | 0.596 | 0.571 | 0.557 | 0.574 | |

Science | ID-based | 0.599 | 0.584 | 0.577 | 0.570 |

Description-based | 0.604 | 0.587 | 0.580 | 0.579 | |

Based on extensive external knowledge acquired during the pre-training process, the generative LLM is enabled to perform the KT task by considering the relationships between KCs. In general, KT models that account for relationships between KCs are more effective at predicting student performance (Chen et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2022). As a result, when an exercise is represented based on its description, the external knowledge of generative LLMs can be fully utilized, resulting in improved prediction performance. Thus, the results of this experiment can be used to answer RQ2 (How can exercises be effectively represented in natural language?) as follows: when aligning generative LLM with KT, representing knowledge concepts in each exercise using a description-based method is more effective.

Effectiveness of fine-tuning

To investigate the effectiveness of fine-tuning, we conducted two experiments: (1) comparison of CLST predictive performance before and after fine-tuning; and (2) analysis of changes in model reliability before and after fine-tuning. The details regarding the fine-tuning are provided in section 3.2.3.

First, to determine whether fine-tuning improves predictive performance, the predictive performance of untuned CLST was evaluated. Table 8 shows the experimental results for CLST's predictive performance (AUC), including the untuned model (0 students). The experimental results showed that the fine-tuned model outperforms the untuned model across all datasets. The model fine-tuned with data from 8 students improved performance by at least 1.55% and up to 5.66% compared to the untuned model. Moreover, the model fine-tuned with 64 students' data outperformed the untuned model by at least 5.33% and up to 11.94% in terms of AUC.

Dataset | Number of Students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | |

NIPS34 | 0.601 | 0.635 | 0.637 | 0.651 | 0.661 |

Algebra05 | 0.645 | 0.655 | 0.661 | 0.702 | 0.722 |

Assist09 | 0.675 | 0.689 | 0.682 | 0.684 | 0.711 |

Science | 0.557 | 0.579 | 0.580 | 0.587 | 0.604 |

Social Studies | 0.552 | 0.574 | 0.557 | 0.571 | 0.596 |

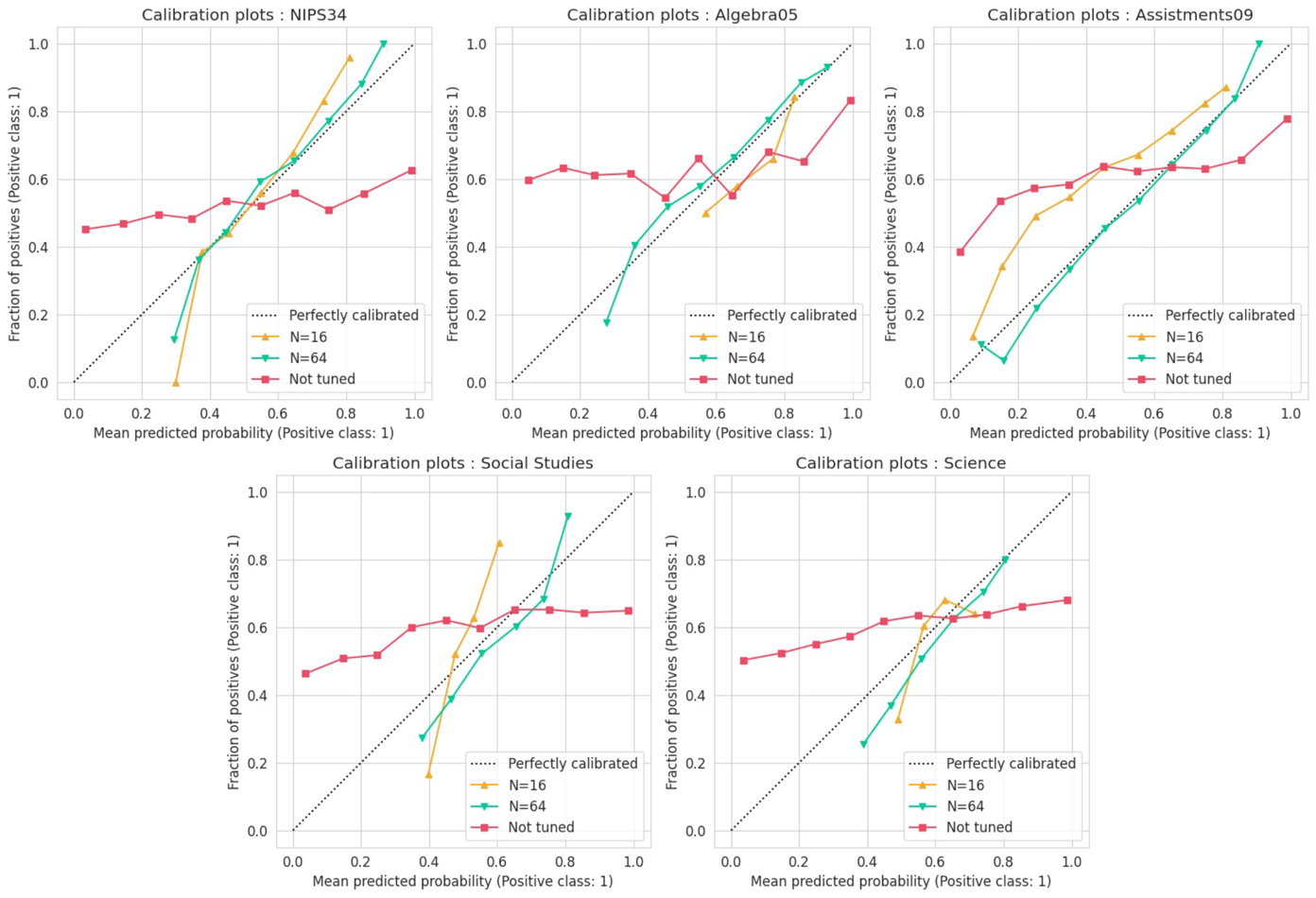

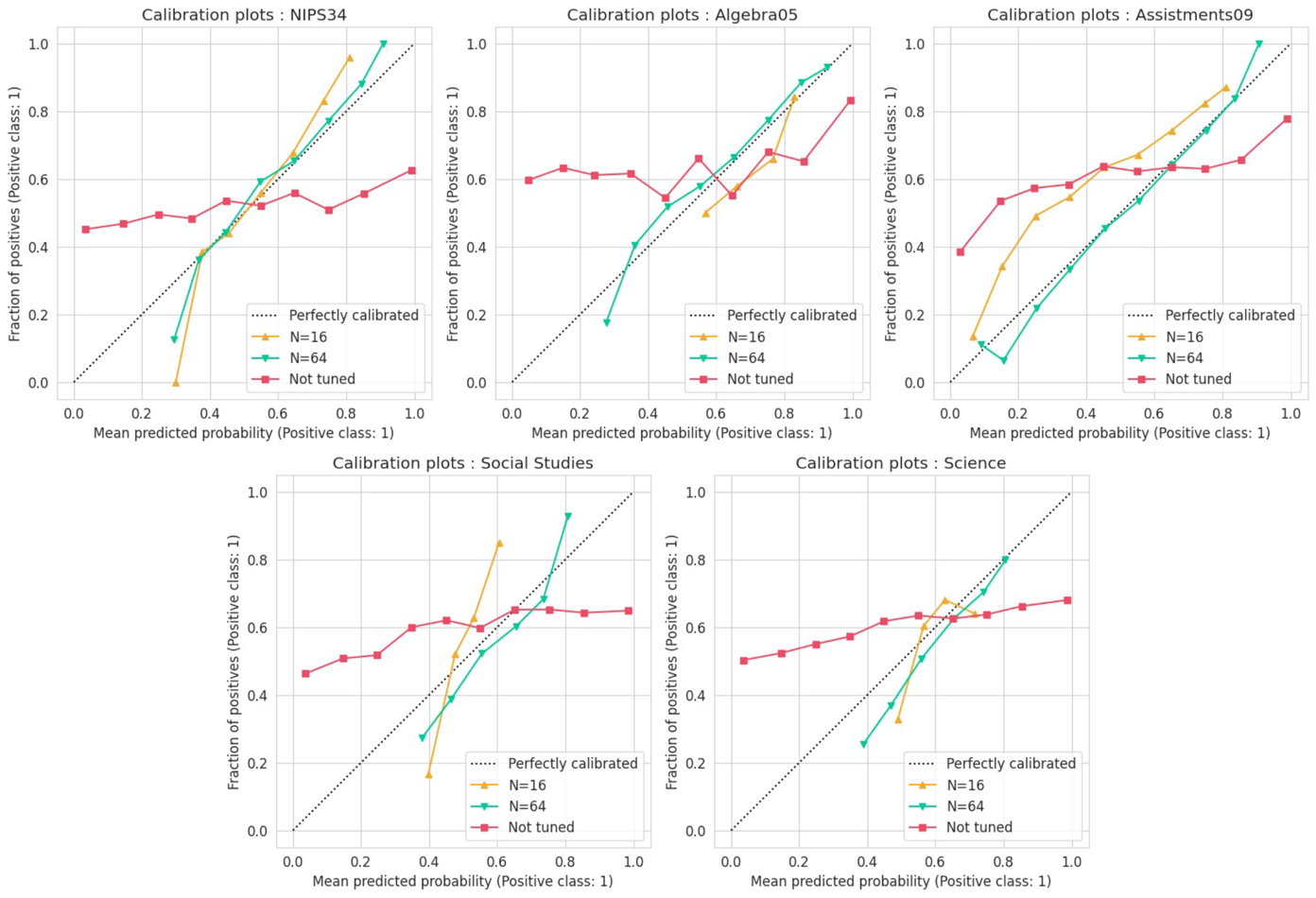

Second, we compared the calibration plot outputs from an untuned model (mistral-7b-instruct-v02, the backbone model selected for this study) and its fine-tuned counterpart.

Figure 5 shows the changes in output calibration as an effect of fine-tuning for each dataset. Each calibration plot is an illustration that compares the average predicted value of a model’s output for each bin (x-axis) with the fraction of positive classes (y-axis). A diagonal dotted line in the figure represents the ideal calibration that a model can achieve by predicting events based on the base rate of occurrences (Gervet et al., 2020). Therefore, the output values are more reliable when the output calibration is closer to the diagonal line. Note that fine-tuning with a small amount of data may narrow the range of output values. As a result, in some cases, the number of dots in Figure 5's output results is expressed differently.

Our experiments demonstrate that the untuned model exhibited poor output calibration; in contrast, output calibration significantly improved as the number of students in the KTLP dataset used for fine-tuning increased from 16 to 64.

The output of a KT model is the probability of correctly answering an exercise that covers a specific KC. This probability is often regarded as the mastery level of that KC (Piech et al., 2015). The output of a KT model can also be used for downstream tasks, such as personalized content recommendations (Ai et al., 2019), making output reliability an essential priority (Gervet et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2022). The results of this experiment demonstrate enhanced reliability when a model is fine-tuned using KTLP-formatted data.

In summary, the experimental results to investigate the effectiveness of fine-tuning demonstrated that it improved CLST's predictive performance across all datasets. Additionally, it was noted that the model's reliability increased as the fine-tuning process advanced. Based on the findings of the two experiments, CLST fine-tuning can be regarded as essential.

Learning trajectory analysis

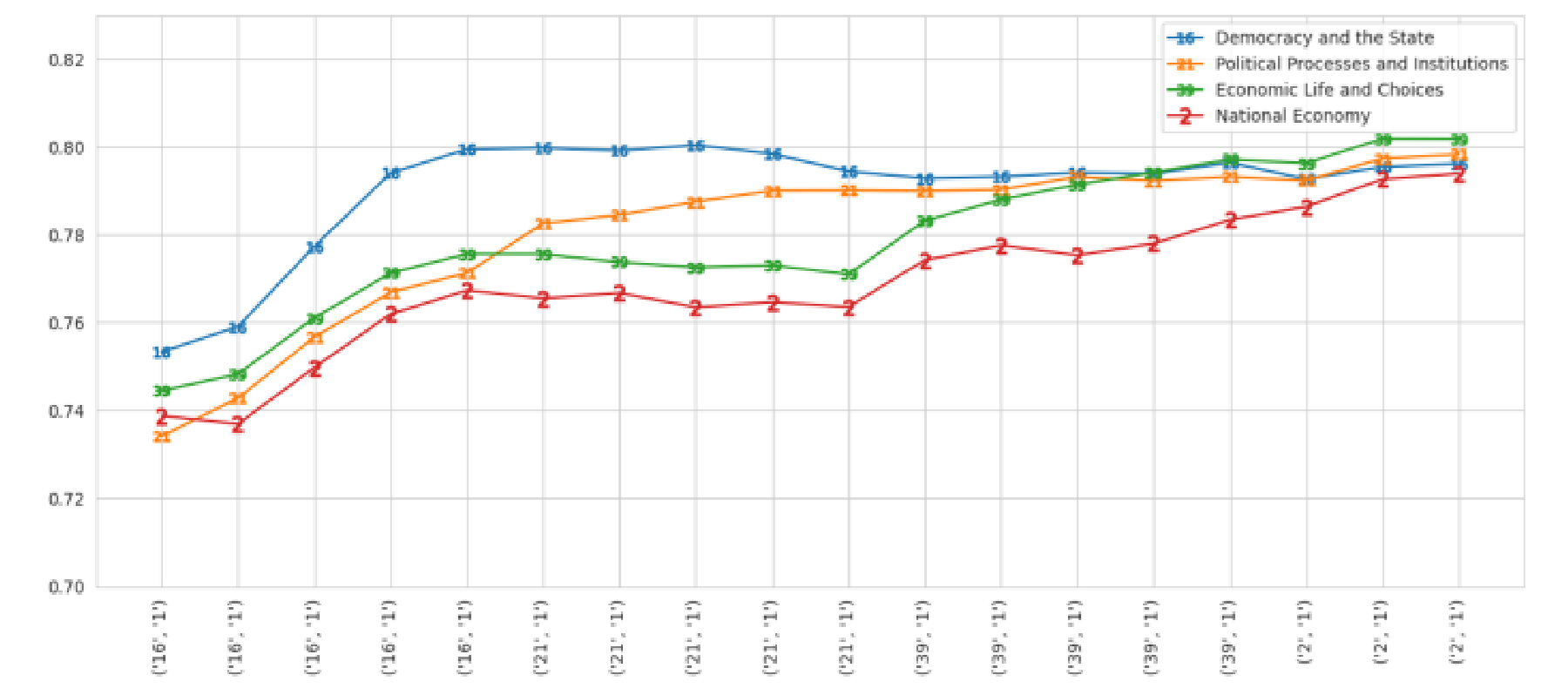

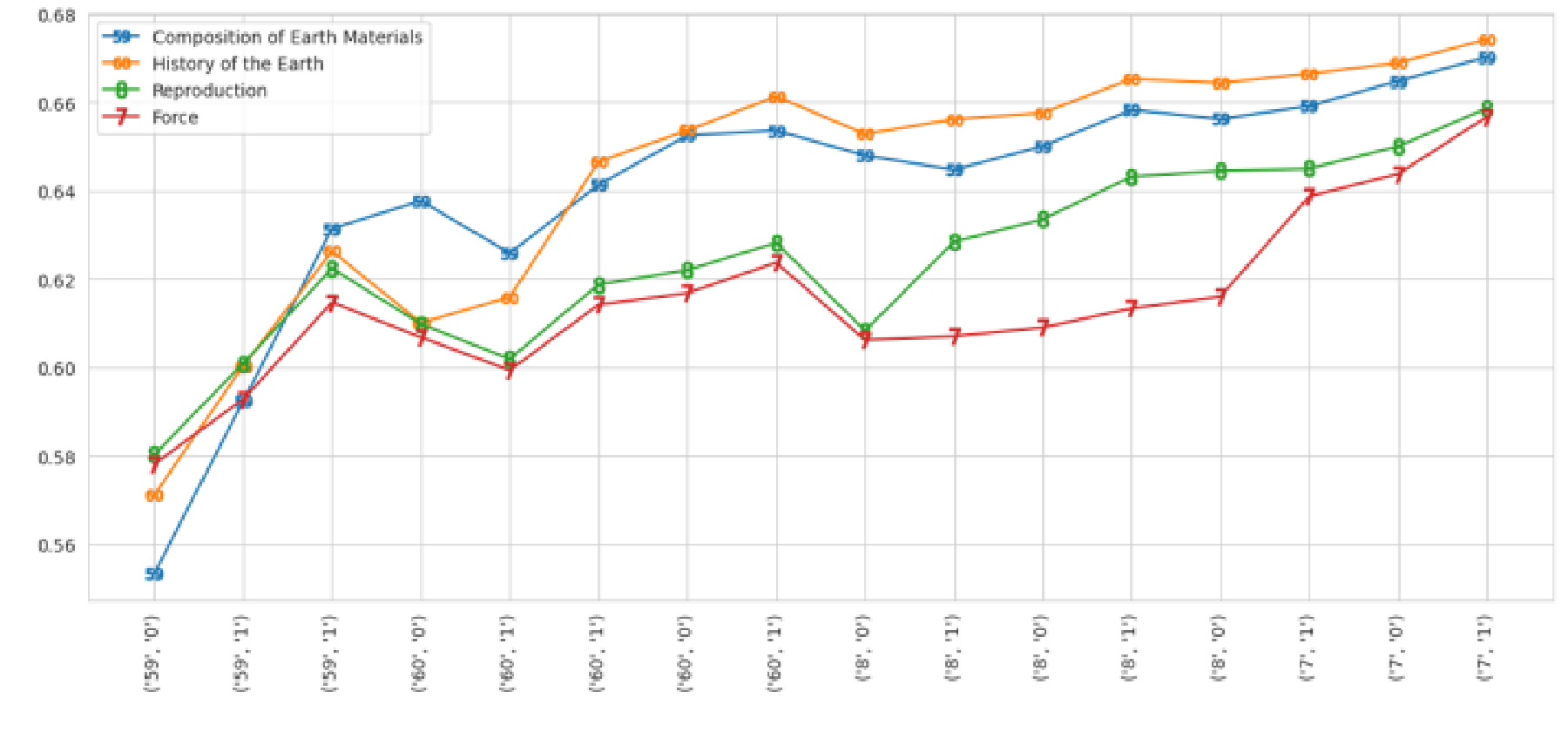

To determine whether the method proposed in this study successfully predicts students’ knowledge states, we visually analyzed the students' understanding of each KC in the process of solving exercises. Random selections of students from the science, social studies, and mathematics datasets were made for this purpose. In mathematics, students were randomly selected from the Assist09 dataset. For each dataset, we used the CLST model fine-tuned with 64 students’ data.

Figures 6 through 9 depict the learning trajectories of the students selected for each subject. Heat maps and line graphs were used to visualize how the mastery level for each KC changed as each student progressed through solving problems for each subject.

The x-axis of each heat map represents the interaction (KC ID, correctness) at each time step, while the y-axis represents the KC of the questions that the student primarily answered. In other words, the value of each cell indicates the change in the mastery level for the corresponding KC after the interaction occurred. The x-axis of the line plot (lower part of Figures) likewise represents the interaction (KC ID, correctness) at each time step, with the y-axis representing mastery level values; thus, each line represents the mastery level of the corresponding KC.

The learning trajectory analysis revealed two observed facts. Initially, each student's knowledge state predicted by CLST was subject to change in accordance with the correctness of the problem. In other words, when a student correctly or incorrectly answers a question about a specific KC, the mastery level of the corresponding KC increases or decreases, respectively. For example, in Figure 6, if the student correctly answered the question about KC-92, the mastery level for the corresponding KC increased, whereas if the student answered the question incorrectly, the mastery level decreased. Similarly, when questions about KC-14 were correctly and incorrectly answered, the mastery level of the corresponding KC (orange line in the figure) rose and fell accordingly.

Second, CLST’s predictions of each student’s knowledge state for related KCs show similar trends. For example, Figure 6 depicts a math student’s learning trajectory, showing changes in mastery levels for KC-13 (scatter plot), KC-14 (proportion), KC-20 (percent of), KC-129 (stem and leaf plot), and KC-92 (fraction addition and subtraction). Among these, KC-13 and KC-129 are both concepts related to plots, and KC-14 and KC-20 are similarly interconnected. Upon examining changes in the students' mastery levels, the trends within these pairs of KCs exhibited mutually similar tendencies. In contrast, the mastery level for KC-92 exhibited a different pattern compared to that of the other KCs.

Furthermore, when a student correctly responded to an item regarding KC-13, the corresponding mastery level increased along with that of the intuitively related KC-129.

Similarly, in the learning trajectory of another math student shown in Figure 7, the mastery levels of related KCs, namely KC-25 (division of fractions) and KC-92 (addition and subtraction of fractions), as well as KC-20 (percent of) and KC-37 (conversion of fractions, decimals, and percents), displayed similar trends.

In the social studies learning trajectory shown in Figure 8, the mastery level of related concepts KC-2 (national economy) and KC-39 (economic life and choices) changed in a similar manner. For the science student shown in Figure 9, the mastery levels of related KCs—KC-59 (composition of earth materials) and KC-60 (history of the earth)—changed in similar patterns.

Consequently, it is possible to infer that CLST estimates the student's knowledge state by examining relationships between KCs.

Inter-skill Influence Analysis

The analysis of the learning trajectory revealed that CLST can predict the student's knowledge state by taking into account the relationships between KCs. To further investigate this, we conducted a quantitative evaluation of the model's behavior. The influence of every pair of skills was calculated in accordance with the methodology outlined in Piech et al. (2015):

where denotes the model’s predicted probability of accurately answering an exercise related to skill , given that an exercise related to skill was answered correctly at the first time step.

Skill name | Most relevant skill | Second most relevant skill |

|---|---|---|

Area Circle | Area Rectangle | Area Triangle |

Addition and Subtraction Integers | Addition and Subtraction Fractions | Addition and Subtraction Positive Decimals |

Division Fractions | Multiplication Fractions | Addition and Subtraction Fractions |

Finding Percents | Conversion of Fraction Decimals Percents | Percents |

Stem and Leaf Plot | Box and Whisker | Scatter Plot |

Skill name | Most relevant skill | Second most relevant skill |

|---|---|---|

Political Processes and Institutions | Democracy and the State | International Politics |

Economic Life and Choices | World Economy | National Economy |

Collection and Utilization of Geographic Information | Inter-regional Networks | Geographical Characteristics of Population |

Meaning of History | National Sovereignty Movement (Independence Movement) | Development of Ancient States |

Climate Environment | Interaction between Nature and Humans | Geographical Attributes |

Skill name | Most relevant skill | Second most relevant skill |

|---|---|---|

Electricity | Energy Conversion | Magnetism |

Biotechnology | Genetics | Structure and Function of Plants |

Plate Tectonics | History of the Earth | Disasters |

Structure and Function of Animals | Genetics | Structure and Function of Plants |

Constituents of Life | Genetics | Biotechnology |

Tables 9 through 11 show the top two skills in terms of influence value for each of five skills from each dataset. The analysis indicates that skills sharing conceptual similarities tend to exert strong mutual influence. For instance, in the mathematics domain, the skills with the highest calculated influence on “Area Circle” were “Area Rectangle” and “Area Triangle,” all of which pertain to the calculation of geometric areas. Similarly, high influence values were observed among skills commonly associated with addition and subtraction, as well as those related to percentages and plotting.

In the case of social studies, strong influence was calculated among skills within thematically consistent domains, such as politics, economics, and geography. A similar pattern was observed in science, where high influence values were found among skills associated with specific subfields, including life science, earth science, and physics.

These findings suggest that the CLST model accounts for inter-skill influence when estimating a student's knowledge state. That is, when a student responds correctly or incorrectly, the predicted probability of success for the corresponding knowledge component increases or decreases accordingly, as well as the probability on related KCs.

Ultimately, the analysis of learning trajectories yields the following answer to RQ3 (Does the proposed model provide a convincing prediction of students’ knowledge states?): the CLST plausibly predicts each student's mastery level and also understands the relationships between KCs.

Predictive performance under cross-domain scenarios

Finally, we examined the performance of CLST in a cross-domain scenario. In this experiment, the terms “domain” and “dataset” are used interchangeably (Zhao et al., 2019). To evaluate predictive performance within subject across platforms, we selected three datasets for the same subject. Specifically, we conducted an experiment using the mathematics subject datasets NIPS34, Algebra05, and Assist09. The sample size from the source dataset was increased to 8, 16, 32, 64, and all samples, which were used to train the model. As described in Section 3.5., we executed each method five times with different random seeds and reported the average outcomes. That is, the models are trained on multiple sampled training sets (e.g., five sets of 64 students in Assist09). For the test data, 20% of the students were randomly selected.

We tuned CLST with samples from one source domain and subsequently evaluated its predictive performance on test samples from another target domain. For example, we evaluated the performance of the CLST tuned with samples from the NIPS34 dataset on the Algebra05 dataset. In addition, we evaluated the performance of DL-based KT models and the CLST trained with the target domain samples. For DL-based models, both training and evaluation were conducted in the target domain. Experiments were conducted when the number of samples in the source domain was small (K≤64) or large (using full data).

The predictive performance evaluated in the target domain after training with a small number of samples (K≤64) is depicted in Figure 10. The target domain is indicated at the top of each figure, and the dataset in parentheses after the model name in the legend represents the training set. For example, CLST(assist) refers to the CLST model trained with the Assist09 dataset. The x-axis of the graph indicates the number of students used for training. The first picture in Figure 10 shows the performance of each model evaluated with the NIPS34 dataset. All DL-based models (DKT(nips), DKVMN(nips), AKT(nips)) were trained with the NIPS34 dataset, which is the target domain. CLST was trained using the NIPS34 dataset (CLST(nips)), as well as other source domain, Algebra05 (CLST(algebra)) and Assist09 (CLST(assist)), and subsequently tested using the NIPS34 data to evaluate its performance. The remaining graphs in Figure 10 are expressed in the same manner.

According to the overall experimental results, CLST tuned with the target domain data, depicted in green, showed the highest performance. Additionally, the CLST trained on a different source domain dataset, denoted by pink dotted lines, outperformed the DL-based KT models trained on the target domain, denoted by purple dotted lines. In particular, in experiments with the Assist09 dataset, the CLST tuned with different domains (such as Algebra05 and NIPS34) demonstrated performance comparable to that tuned with the target domain.

Target domain | CLST (trained with target domain) | CLST (trained with source domain) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

K=0 | K=16 | K=32 | K=64 | Source domain | K=Full | |

NIPS34 | 0.601 | 0.637 | 0.651 | 0.661 | Algebra05 | 0.659 |

Assist09 | 0.649 | |||||

Algebra05 | 0.665 | 0.661 | 0.702 | 0.722 | NIPS34 | 0.655 |

Assist09 | 0.684 | |||||

Assist09 | 0.688 | 0.682 | 0.684 | 0.711 | NIPS34 | 0.690 |

Algebra05 | 0.706 | |||||

(K= the number of students in train dataset)

Table 12 compares the predictive performance on the target domain after training CLST with a large number of source domain samples to the predictive performance after training with a small number of target domain samples. In Table 12, the representation of “K=Full” indicates that all samples in the source domain were used for training. Results in which the CLST trained with source data outperformed the model trained with target data are shaded in gray.

The experimental results indicated that the performance of the CLST trained with source domain was generally superior to that of the CLST trained with target domain when the number of training samples in the target domain was small (K≤32). When the number of target domain samples for training is 16 or less, CLST trained with source domain performs better in all cases.

In fact, the majority of current research in the field of KT has primarily concentrated on domain-specific cases. However, real-world scenarios may present obstacles to this approach, such as the inability to obtain data on student-exercise interactions. In such cases, domain-specific models might not function effectively as a result of insufficient data, making the evaluation of cross-domain generalization capacity critical when deploying KT models in practice. Therefore, the scarcity of information from the target domain can be addressed by utilizing information from other domains as training data in cold-start scenarios (Cheng et al., 2022).

Experimental results indicate that CLST exhibits high cross-domain performance when employing other source domains in scenarios where the number of target domain samples is limited. Therefore, in the cold start scenario, where there is limited target data during the initial stages of developing an ITS, CLST trained using an alternative source data with access to exercise representations can demonstrate satisfactory performance.

Ultimately, this experiment reveals the following answer to RQ4 (Is the proposed model effective at predicting student knowledge in cross-domain scenarios?): models trained with the CLST are more generalizable than ID-based models across domains; therefore, the CLST can be a promising option when it is necessary to estimate students' mastery level in circumstances where data is scarce and it is difficult to secure sufficient student-exercise interactions.

Conclusion and limitation

In this study, we developed the CLST, which utilizes a generative LLM as a knowledge tracer. Most existing KT models are designed based on an ID-based approach, which exhibits poor predictive performance in cold-start cases with insufficient data. In contrast, the CLST demonstrates high performance even in cold-start scenarios and exhibits robust cross-domain generalizability. For the experiments, we collected data on the subjects of mathematics, social studies, and science. Subsequently, by expressing the problem-solving data in natural language, we framed the KT task as an NLP task and fine-tuned a generative LLM using the formatted KT dataset.

The experimental results showed that the CLST outperformed the baseline models by up to 24.52% (mathematics), 9.62% (social studies), and 11.82% (science) in situations where the number of students in the training data was insufficient. Furthermore, the ablation study showed that the description-based method applied in CLST, which represents each exercise with its description, achieved better performance than the conventional ID-based method. Additionally, the reliability experiment confirmed that fine-tuning with KTLP-formatted data enhances model reliability. Moreover, the learning trajectory analysis revealed that the CLST plausibly predicts students' mastery levels and understands the relationships between KCs. Additionally, as a result of the Inter-skill Influence analysis, the CLST can predict that when a student answers correctly or incorrectly, the likelihood of success on the associated KC rises or falls accordingly, and similar changes are observed in the probabilities for related KCs. Finally, the cross-domain KT experiments verified that CLST is generalizable across multiple domains.

The CLST's superior performance in comparison to specialized KT models is likely attributable to its capacity to leverage its extensive intrinsic knowledge and high-quality textual feature representations (Wu et al., 2024), as well as the use of carefully designed KTLP prompts that explicitly encode students' sequential problem-solving processes. Furthermore, our analysis demonstrates that the CLST model effectively captures inter-skill influences rather than merely predicting overall performance, thus enhancing its accuracy in estimating student mastery.

The results of this study have practical implications, serving as a guide for educational institutions and EdTech companies aiming to promote personalized learning through the development of ITS capable of estimating students’ knowledge states. Additionally, it offers theoretical implications by shedding light on strategies for leveraging generative LLMs in the KT domain.

Although the effectiveness of CLST has been demonstrated in numerous experiments, it has several limitations as follows: first, while fine-tuning LLMs can yield high performance, it comes at a significant cost. For example, fine-tuning the CLST model on the Algebra05 dataset took approximately 6.8 hours, consuming energy around 1.7kWh, whereas fine-tuning the AKT model on the same dataset required only 50 seconds and consumed just 3.47Wh, making it 490 times more energy efficient. These findings highlight the trade-off between model performance and energy consumption, suggesting that large-scale models may not be practical in resource-constrained environments due to their high energy demands. Second, as the data volume increases, the predictive performance of CLST can be caught up by that of traditional models since CLST has been proposed to improve performance in cold-start context. Table B of the Appendix B (Section 6.2) presents experimental results from a larger dataset related to this issue. Third, the performance of CLST can deteriorate as sequence length increases. Fourth, due to its nature as a large black-box LLM, the proposed model lacks interpretability, making it difficult to understand how it makes predictions.

Fifth, the analysis of learning trajectories suggests that CLST may capture relationships between knowledge components (KCs), enabling transfer-based inference of mastery. However, this also poses potential risks. For instance, understanding "proportion" does not always ensure correct performance on tasks involving "percent of." Overestimating mastery based on such relationships could lead adaptive systems to assign tasks beyond a student’s actual ability. Thus, inferred KC relationships should be used cautiously and treated as supplementary information. At the same time, this limitation suggests a promising direction for future research on improving the precision of transfer-based inference in personalized learning. Lastly, it has the potential to yield even higher predictive performance. For example, the inclusion of additional tasks may increase performance on the target task (Wei et al., 2021). Therefore, it is worthwhile to contemplate future research endeavors to align generative LLMs as superior knowledge tracers by integrating a variety of educational tasks related to KT (e.g., difficulty estimation, KC relation prediction, etc.) into the fine-tuning process.

Appendices

Appendix A: Comparison of prompt templates

Neshaei et al. (2024) utilized generative LLMs in the KT task. However, it was limited in that it did not fully leverage the capabilities of generative LLMs, as exercises were simply represented using IDs. Moreover, the sequence of problem-solving by students is crucial in the KT task, whereas the study in question only considered the number of correct and incorrect answers by each student. The CLST proposed in this study differs significantly from the one conducted by Neshaei et al. (2024) in that it expresses exercises using natural language descriptions (e.g., KC names) and reflects the problem-solving sequence. Accordingly, the CLST proposed in this study has a significant difference in the prompt template used to fine-tune LLM from the study conducted by Neshaei et al. (2024). Figures A1 and A2 depict examples of prompt templates for the models proposed in each study.

Appendix B: results of large dataset experiments

Table B1 presents detailed results of the experiments using larger datasets, where the best AUC score for each trial is bolded. Performance was evaluated for the NIPS34 and Assist09 datasets from sample sizes ranging from 500 students to full data utilization. For Algebra05 dataset, performance was evaluated using the full data samples. The term "full data" refers to the utilization of 80% of all students in each dataset, with the exception of samples for testing. Consequently, performance was evaluated for a maximum of 3,934 students in the NIPS34 dataset, 456 students in the Algebra05 dataset, and 2,915 students in the Assist09 dataset. For social studies and science datasets, performance was measured when the number of students was 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000. Confidence intervals are presented for each experimental result.

Experimental results show that CLST performs well even on large datasets. However, as the dataset size increases, the performance gap between CLST and the other models generally tends to narrow. In particular, in the NIPS34 dataset, other models catch up with the performance of CLST when the number of students used for training is more than 2000.

In summary, CLST is proposed to improve cold start performance by leveraging LLM capabilities, but it also performs well on larger datasets. Nevertheless, there is a possibility that CLST's performance may be surpassed by other traditional models as the dataset's size increases.

Dataset | # Students | Average AUC | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Traditional | DL-based | NLP-enhanced | Global KC | LLM-based | ||||||||||

BKT | IRT | PFA | DKT | DKVMN | AKT | DKT_text | DKVMN_text | AKT_text | BKT | DKT | Neshaei et al | CLST | ||

NIPS34 | 500 | 0.608 ±0.008 | 0.620 ±0.024 | 0.659 ±0.009 | 0.640 ±0.007 | 0.656 ±0.008 | 0.656 ±0.005 | 0.661 ±0.009 | 0.656 ±0.007 | 0.652 ±0.006 | 0.660 ±0.009 | 0.601 ±0.011 | 0.632 ±0.008 | 0.676 ±0.006 |

1000 | 0.611 ±0.007 | 0.635 ±0.020 | 0.657 ±0.011 | 0.666 ±0.008 | 0.662 ±0.007 | 0.663 ±0.011 | 0.666 ±0.007 | 0.658 ±0.007 | 0.664 ±0.008 | 0.659 ±0.009 | 0.596 ±0.009 | 0.639 ±0.006 | 0.680 ±0.006 | |

1500 | 0.611 ±0.007 | 0.644 ±0.021 | 0.653 ±0.012 | 0.668 ±0.009 | 0.661 ±0.007 | 0.675 ±0.079 | 0.669 ±0.006 | 0.657 ±0.006 | 0.665 ±0.005 | 0.659 ±0.009 | 0.607 ±0.011 | 0.640 ±0.007 | 0.681 ±0.008 | |

2000 | 0.612 ±0.007 | 0.647 ±0.019 | 0.648 ±0.015 | 0.668 ±0.008 | 0.661 ±0.008 | 0.696 ±0.005 | 0.669 ±0.008 | 0.657 ±0.007 | 0.677 ±0.009 | 0.659 ±0.009 | 0.598 ±0.006 | 0.648 ±0.006 | 0.682 ±0.007 | |

Full | 0.613 ±0.007 | 0.654 ±0.019 | 0.643 ±0.011 | 0.671 ±0.009 | 0.661 ±0.008 | 0.729 ±0.006 | 0.672 ±0.006 | 0.656 ±0.006 | 0.701 ±0.005 | 0.659 ±0.009 | 0.630 ±0.006 | 0.727 ±0.006 | 0.700 ±0.006 | |

Algebra05 | Full | 0.730 ±0.005 | 0.653 ±0.009 | 0.631 ±0.005 | 0.742 ±0.003 | 0.730 ±0.007 | 0.737 ±0.003 | 0.757 ±0.004 | 0.708 ±0.008 | 0.746 ±0.005 | 0.636 ±0.003 | 0.581 ±0.007 | 0.713 ±0.007 | 0.760 ±0.006 |

Assist09 | 500 | 0.714 ±0.006 | 0.582 ±0.003 | 0.657 ±0.007 | 0.697 ±0.008 | 0.715 ±0.005 | 0.706 ±0.008 | 0.720 ±0.007 | 0.687 ±0.005 | 0.706 ±0.008 | 0.707 ±0.007 | 0.598 ±0.008 | 0.710 ±0.007 | 0.734 ±0.007 |

1000 | 0.722 ±0.006 | 0.607 ±0.003 | 0.660 ±0.004 | 0.711 ±0.007 | 0.708 ±0.007 | 0.723 ±0.004 | 0.732 ±0.006 | 0.688 ±0.006 | 0.717 ±0.005 | 0.713 ±0.007 | 0.618 ±0.006 | 0.710 ±0.007 | 0.743 ±0.007 | |

1500 | 0.727 ±0.006 | 0.626 ±0.003 | 0.658 ±0.009 | 0.724 ±0.006 | 0.703 ±0.007 | 0.729 ±0.006 | 0.740 ±0.006 | 0.687 ±0.004 | 0.725 ±0.007 | 0.716 ±0.006 | 0.614 ±0.006 | 0.716 ±0.004 | 0.747 ±0.005 | |

2000 | 0.728 ±0.005 | 0.633 ±0.003 | 0.654 ±0.008 | 0.734 ±0.005 | 0.706 ±0.006 | 0.735 ±0.005 | 0.744 ±0.005 | 0.689 ±0.004 | 0.731 ±0.006 | 0.717 ±0.006 | 0.640 ±0.008 | 0.725 ±0.006 | 0.750 ±0.007 | |

Full | 0.729 ±0.006 | 0.645 ±0.003 | 0.660 ±0.006 | 0.742 ±0.006 | 0.707 ±0.006 | 0.742 ±0.005 | 0.749 ±0.006 | 0.685 ±0.004 | 0.736 ±0.006 | 0.719 ±0.005 | 0.644 ±0.009 | 0.734 ±0.005 | 0.751 ±0.007 | |

Science | 500 | 0.595 ±0.003 | 0.559 ±0.002 | 0.597 ±0.003 | 0.560 ±0.004 | 0.569 ±0.005 | 0.538 ±0.008 | 0.584 ±0.011 | 0.591 ±0.004 | 0.588 ±0.007 | 0.611 ±0.003 | 0.541 ±0.008 | 0.612 ±0.007 | 0.618 ±0.006 |

1000 | 0.601 ±0.002 | 0.575 ±0.002 | 0.600 ±0.003 | 0.593 ±0.005 | 0.591 ±0.003 | 0.592 ±0.005 | 0.610 ±0.003 | 0.603 ±0.002 | 0.604 ±0.004 | 0.610 ±0.002 | 0.557 ±0.007 | 0.615 ±0.008 | 0.623 ±0.005 | |

1500 | 0.607 ±0.002 | 0.587 ±0.001 | 0.597 ±0.008 | 0.607 ±0.004 | 0.597 ±0.001 | 0.607 ±0.003 | 0.618 ±0.001 | 0.600 ±0.003 | 0.609 ±0.002 | 0.611 ±0.002 | 0.564 ±0.008 | 0.620 ±0.004 | 0.626 ±0.004 | |

2000 | 0.605 ±0.003 | 0.592 ±0.002 | 0.610 ±0.004 | 0.613 ±0.001 | 0.595 ±0.003 | 0.610 ±0.003 | 0.621 ±0.002 | 0.601 ±0.003 | 0.614 ±0.002 | 0.611 ±0.002 | 0.568 ±0.016 | 0.613 ±0.005 | 0.630 ±0.005 | |

Social Study | 500 | 0.596 ±0.002 | 0.566 ±0.003 | 0.599 ±0.005 | 0.593 ±0.006 | 0.602 ±0.007 | 0.589 ±0.006 | 0.609 ±0.004 | 0.600 ±0.008 | 0.594 ±0.006 | 0.608 ±0.004 | 0.540 ±0.006 | 0.613 ±0.006 | 0.616 ±0.006 |

1000 | 0.601 ±0.002 | 0.589 ±0.005 | 0.604 ±0.003 | 0.593 ±0.004 | 0.602 ±0.004 | 0.589 ±0.007 | 0.609 ±0.005 | 0.600 ±0.004 | 0.594 ±0.004 | 0.608 ±0.004 | 0.546 ±0.009 | 0.607 ±0.005 | 0.620 ±0.006 | |

1500 | 0.602 ±0.004 | 0.601 ±0.003 | 0.587 ±0.017 | 0.605 ±0.005 | 0.609 ±0.005 | 0.602 ±0.003 | 0.616 ±0.004 | 0.604 ±0.006 | 0.605 ±0.004 | 0.609 ±0.004 | 0.557 ±0.009 | 0.612 ±0.006 | 0.627 ±0.005 | |

2000 | 0.603 ±0.002 | 0.609 ±0.003 | 0.602 ±0.007 | 0.612 ±0.004 | 0.611 ±0.005 | 0.607 ±0.006 | 0.620 ±0.004 | 0.605 ±0.005 | 0.607 ±0.004 | 0.608 ±0.004 | 0.565 ±0.006 | 0.605 ±0.007 | 0.628 ±0.004 | |

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the High-Performance Computing Support Project (G2025-0839), funded by the Government of the Republic of Korea (Ministry of Science and ICT).

References

- Abdelghani, R., Wang, Y.H., Yuan, X., Wang, T., Lucas, P., Sauzéon, H., and Oudeyer, P.Y. 2024. GPT-3-Driven Pedagogical Agents to Train Children's Curious Question-Asking Skills. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 34, 2, 483-518.

- Abdelrahman, G., and Wang, Q. 2019. Knowledge Tracing with Sequential Key-Value Memory Networks. In Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 175-184.

- Abdelrahman, G., Wang, Q., and Nunes, B. 2023. Knowledge Tracing: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 55, 11, 1-37.

- Abu-Rasheed, H., Weber, C., and Fathi, M. 2024. Knowledge Graphs as Context Sources for LLM-Based Explanations of Learning Recommendations. In 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 1-5.

- Ai, F., Chen, Y., Guo, Y., Zhao, Y., Wang, Z., Fu, G., and Wang, G. 2019. Concept-Aware Deep Knowledge Tracing and Exercise Recommendation in an Online Learning System. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, 240-245.

- Bulut, O., and Yildirim-Erbasli, S.N. 2022. Automatic Story and Item Generation for Reading Comprehension Assessments with Transformers. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education 9, Special Issue, 72-87.

- Chen, P., Lu, Y., Zheng, V.W., and Pian, Y. 2018. Prerequisite-Driven Deep Knowledge Tracing. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), 39-48.

- Cheng, S., Liu, Q., Chen, E., Zhang, K., Huang, Z., Yin, Y., Huang, X., and Su, Y. 2022. AdaptKT: A Domain Adaptable Method for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 123-131.

- Colpo, M.P., Primo, T.T., and de Aguiar, M.S. 2024. Lessons Learned from the Student Dropout Patterns on COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis Supported by Machine Learning. British Journal of Educational Technology 55, 2, 560-585.

- Corbett, A.T., and Anderson, J.R. 1994. Knowledge Tracing: Modeling the Acquisition of Procedural Knowledge. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 4, 253-278.

- Dai, W., Tsai, Y.S., Lin, J., Aldino, A., Jin, H., Li, T., Gašević, D., and Chen, G. 2024. Assessing the Proficiency of Large Language Models in Automatic Feedback Generation: An Evaluation Study. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 7, 100299.

- Dai, W., Lin, J., Jin, H., Li, T., Tsai, Y.S., Gašević, D., and Chen, G. 2023. Can Large Language Models Provide Feedback to Students? A Case Study on ChatGPT. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 323-325.

- Delianidi, M., and Diamantaras, K. 2023. KT-Bi-GRU: Student Performance Prediction with a Bi-Directional Recurrent Knowledge Tracing Neural Network. Journal of Educational Data Mining 15, 2, 1-21.

- Do Viet, T., and Markov, K. 2023. Using Large Language Models for Bug Localization and Fixing. In 2023 12th International Conference on Awareness Science and Technology (iCAST), 192-197.

- Doughty, J., Wan, Z., Bompelli, A., Qayum, J., Wang, T., Zhang, J., Zheng, Y., Doyle, A., Sridhar, P., Agarwal, A., Bogart, C., Keylor, E., Kultur, C., Savelka, J., and Sakr, M. 2024. A Comparative Study of AI-Generated (GPT-4) and Human-Crafted MCQs in Programming Education. In Proceedings of the 26th Australasian Computing Education Conference, 114-123.

- Emerson, A., Min, W., Azevedo, R., and Lester, J. 2023. Early Prediction of Student Knowledge in Game-Based Learning with Distributed Representations of Assessment Questions. British Journal of Educational Technology 54, 1, 40-57.

- Fan, Y., Jiang, F., Li, P., and Li, H. 2023. GrammarGPT: Exploring Open-Source LLMs for Native Chinese Grammatical Error Correction with Supervised Fine-Tuning. In CCF International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing, 69-80.

- Feng, M., Heffernan, N., and Koedinger, K. 2009. Addressing the Assessment Challenge with an Online System that Tutors as It Assesses. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 19, 243-266.

- Gervet, T., Koedinger, K., Schneider, J., and Mitchell, T. 2020. When Is Deep Learning the Best Approach to Knowledge Tracing? Journal of Educational Data Mining 12, 3, 31-54.

- Ghosh, A., Heffernan, N., and Lan, A.S. 2020. Context-Aware Attentive Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2330-2339.

- Hu, E.J., Shen, Y., Wallis, P., Allen-Zhu, Z., Li, Y., Wang, S., and Chen, W. 2022. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. ICLR 1, 2, 3.

- Idrissi, N., Zellou, A., Hourrane, O., Bakkoury, Z., and Benlahmar, E.H. 2019. Addressing Cold Start Challenges in Recommender Systems: Towards a New Hybrid Approach. In 2019 International Conference on Smart Applications, Communications and Networking (SmartNets), 1-6.

- Jiang, A.Q., Sablayrolles, A., Mensch, A., Bamford, C., Chaplot, D.S., Casas, D.D.L., Bressand, F., Lengyel, G., Lample, G., Saulnier, L., Lavaud, L.R., Lachaux, M., Stock, P., Scao, T.L., Lavril, T., Wang, T., Lacroix, T., and Sayed, W.E. 2023. Mistral 7b. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06825.

- Jin, M., Wen, Q., Liang, Y., Zhang, C., Xue, S., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Li, X., Pan, S., Tseng, V.S., Zheng, Y., Chen, L., and Xiong, H. 2023. Large Models for Time Series and Spatio-Temporal Data: A Survey and Outlook. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.10196.

- Jung, H., Yoo, J., Yoon, Y., and Jang, Y. 2023. Language Proficiency Enhanced Knowledge Tracing. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, 3-15.

- Kim, S., Kim, W., Jung, H., and Kim, H. 2021. DiKT: Dichotomous Knowledge Tracing. In Intelligent Tutoring Systems: 17th International Conference, ITS 2021, Virtual Event, June 7-11, 2021, Proceedings 17, 41-51.

- Kuo, B.C., Chang, F.T., and Bai, Z.E. 2023. Leveraging LLMs for Adaptive Testing and Learning in Taiwan Adaptive Learning Platform (TALP). In LLM@AIED, 101-110.

- Lee, W., Chun, J., Lee, Y., Park, K., and Park, S. 2022. Contrastive Learning for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, 2330-2338.

- Li, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, D., and Chen, L. 2023. Large Language Models for Generative Recommendation: A Survey and Visionary Discussions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.01157.

- Liu, Y., Yang, Y., Chen, X., Shen, J., Zhang, H., and Yu, Y. 2020. Improving Knowledge Tracing via Pre-training Question Embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.05031.

- Liu, Z., Liu, Q., Chen, J., Huang, S., Tang, J., and Luo, W. 2022. pyKT: A Python Library to Benchmark Deep Learning Based Knowledge Tracing Models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 18542-18555.

- Lu, Y., Chen, P., Pian, Y., and Zheng, V.W. 2022. CMKT: Concept Map Driven Knowledge Tracing. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 15, 4, 467-480.

- Malik, A., Wu, M., Vasavada, V., Song, J., Coots, M., Mitchell, J., Goodman, N., and Piech, C. 2019. Generative Grading: Near Human-Level Accuracy for Automated Feedback on Richly Structured Problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.09916.

- Nakagawa, H., Iwasawa, Y., and Matsuo, Y. 2019. Graph-Based Knowledge Tracing: Modeling Student Proficiency Using Graph Neural Network. In IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence, 156-163.

- Neshaei, S.P., Davis, R.L., Hazimeh, A., Lazarevski, B., Dillenbourg, P., and Käser, T. 2024. Towards Modeling Learner Performance with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14661.

- Ni, L., Wang, S., Zhang, Z., Li, X., Zheng, X., Denny, P., and Liu, J. 2024. Enhancing Student Performance Prediction on Learnersourced Questions with SGNN-LLM Synergy. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 38, 21, 23232-23240.

- Pandey, S., and Karypis, G. 2019. A Self-Attentive Model for Knowledge Tracing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.06837.

- Pardos, Z.A., and Bhandari, S. 2023. Learning Gain Differences Between ChatGPT and Human Tutor Generated Algebra Hints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06871.

- Pardos, Z.A., and Bhandari, S. 2024. ChatGPT-Generated Help Produces Learning Gains Equivalent to Human Tutor-Authored Help on Mathematics Skills. PLoS ONE 19, 5, e0304013.

- Pavlik, P.I., Jr., Cen, H., and Koedinger, K.R. 2009. Performance Factors Analysis–A New Alternative to Knowledge Tracing. In Artificial Intelligence in Education, 531-538. IOS Press.

- Peng, C., Yang, X., Chen, A., Smith, K.E., PourNejatian, N., Costa, A.B., Martin, C., Flores, M.G., Zhang, Y., Magoc, T., Lipori, G., Mitchell, D.A., Ospina, N.S., Ahmed, M.M., Hogan, W.R., Shenkman, E.A., Guo, Y., Bian, J., and Wu, Y. 2023. A Study of Generative Large Language Model for Medical Research and Healthcare. NPJ Digital Medicine 6, 1, 210.

- Piech, C., Bassen, J., Huang, J., Ganguli, S., Sahami, M., Guibas, L.J., and Sohl-Dickstein, J. 2015. Deep Knowledge Tracing. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28.

- Sahebi, S., and Cohen, W.W. 2011. Community-Based Recommendations: A Solution to the Cold Start Problem. In Workshop on Recommender Systems and the Social Web, RSWEB.

- Sethi, R., and Mehrotra, M. 2021. Cold Start in Recommender Systems—A Survey from Domain Perspective. In Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things: Proceedings of ICICI 2020, 223-232. Springer Singapore.

- Shen, S., Liu, Q., Chen, E., Huang, Z., Huang, W., Yin, Y., Su, Y., and Wang, S. 2021. Learning Process-Consistent Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 1452-1460.

- Shen, S., Liu, Q., Huang, Z., Zheng, Y., Yin, M., Wang, M., and Chen, E. 2024. A Survey of Knowledge Tracing: Models, Variants, and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 17, 1898-1919.

- Sridhar, P., Doyle, A., Agarwal, A., Bogart, C., Savelka, J., and Sakr, M. 2023. Harnessing LLMs in Curricular Design: Using GPT-4 to Support Authoring of Learning Objectives. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.17459.

- Stamper, J., Niculescu-Mizil, A., Ritter, S., Gordon, G.J., and Koedinger, K.R. 2010. Challenge Data Set from KDD Cup 2010 Educational Data Mining Challenge.

- Sun, J., Wei, M., Feng, J., Yu, F., Li, Q., and Zou, R. 2024. Progressive Knowledge Tracing: Modeling Learning Process from Abstract to Concrete. Expert Systems with Applications 238, 122280.

- Tey, F.J., Wu, T.Y., Lin, C.L., and Chen, J.L. 2021. Accuracy Improvements for Cold-Start Recommendation Problem Using Indirect Relations in Social Networks. Journal of Big Data 8, 1-18.

- Van Der Linden, W.J., and Hambleton, R.K. 1997. Item Response Theory: Brief History, Common Models, and Extensions. In Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory, 1-28. Springer New York.

- Vie, J.J., and Kashima, H. 2019. Knowledge Tracing Machines: Factorization Machines for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 33, 1, 750-757.

- Wang, C., Ma, W., Zhang, M., Lv, C., Wan, F., Lin, H., Tang, T., Liu, Y., and Ma, S. 2021. Temporal Cross-Effects in Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 517-525.

- Wang, Q., and Mousavi, A. 2023. Which Log Variables Significantly Predict Academic Achievement? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology 54, 1, 142-191.

- Wang, Z., Lamb, A., Saveliev, E., Cameron, P., Zaykov, Y., Hernández-Lobato, J.M., Turner, R.E., Baraniuk, R.G., Barton, C., Jones, S.P., Woodhead, S., and Zhang, C. 2020. Instructions and Guide for Diagnostic Questions: The NeurIPS 2020 Education Challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.12061.

- Wei, J., Bosma, M., Zhao, V.Y., Guu, K., Yu, A.W., Lester, B., Du, N., Dai, A.M., and Le, Q.V. 2021. Finetuned Language Models Are Zero-Shot Learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.01652.

- Weng, L.T., Xu, Y., Li, Y., and Nayak, R. 2008. Exploiting Item Taxonomy for Solving Cold-Start Problem in Recommendation Making. In 2008 20th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence 2, 113-120.