Abstract

Recent research has explored the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) to develop qualitative codebooks, mainly for inductive work with large datasets, where manual review is impractical. Although these efforts show promise, they often neglect the theoretical grounding essential to many types of qualitative analysis. This paper investigates the potential of GPT-4o to support theory-informed codebook development across two educational contexts. In the first study, we employ a three-step approach—drawing on Winne & Hadwin’s and Zimmerman’s Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) theories, think-aloud data, and human refinement—to evaluate GPT-4o’s ability to generate high-quality, theory-aligned codebooks. Results indicate that GPT-4o can effectively leverage its knowledge base to identify SRL constructs reflected in student problem-solving behavior. In the second study, we extend this approach to a STEM game-based learning context guided by Hidi & Renninger’s four-phase model of Interest Development. We compare four prompting strategies: no theories provided, theories named, full references given, and full-text theory papers supplied. Human evaluations show that naming the theory without including full references produced the most practical and usable codebook, while supplying full papers to the prompt enhanced theoretical alignment but reduced applicability. These findings suggest that GPT-4o can be a valuable partner in theory-driven qualitative research when grounded in well-established frameworks, but that attention to prompt design is required. Our results show that widely available foundation models—trained on large-scale open web and licensed datasets—can effectively distill established educational theories to support qualitative research and codebook development. The code for our codebook development process and all the employed prompts and codebooks produced by GPT are available for replication purposes at: https://osf.io/g3z4x

Keywords

Introduction

Qualitative analysis has been used in the learning sciences to systematically examine large volumes of rich, multimodal data (e.g., interview transcripts, field notes, and video recordings) to identify patterns and elaborate insightful and trustworthy interpretations (Gibbs, 2018). While earlier work in Educational Data Mining (EDM) has leveraged qualitative research as a mixed-methods supplement to quantitative results, more recent work has sought to quantify the type of data often used in qualitative research to reveal systematic patterns in larger, complex datasets (e.g., Quantitative Ethnography, Shaffer et al., 2016). A key component of this approach is qualitative coding, where researchers identify and label themes within the data to evaluate their prevalence and guide further analysis (Saldaña, 2021; Shaffer and Ruis, 2021). Qualitative coding is often described as taking either an inductive, bottom-up approach, in which constructs are derived directly from the data itself (Braun and Clarke, 2012), or a deductive, top-down approach, in which codes are applied based on existing codebooks or theoretical frameworks (Bingham and Witkowsky, 2021).

Although inductive and deductive approaches are often treated as distinct, codebook development is rarely purely inductive or deductive (Charmaz, 1983; Weston et al., 2001). To achieve a high-quality codebook and coding, Weston et al. (2001) propose that codebook development should be conducted iteratively by human experts through a comprehensive review and understanding of relevant literature, theoretical frameworks, the cultural context of the data, and the data itself. However, manually examining an entire dataset can be time-consuming or even unfeasible for large datasets. In such cases, researchers could review subsets of the data to inductively identify key constructs guiding their research. However, this approach carries the risk of selecting a subset that may lack examples of constructs or codes prevalent in the uninspected portions of the dataset, potentially missing important insights that could lead to different conclusions (Guest et al., 2006).

Since the recent emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs), some researchers have tested their ability to analyze entire datasets, identify key themes or constructs, and inductively develop a codebook to guide qualitative investigations (Barany et al., 2024; De Paoli, 2024; Gao et al., 2024). For example, Barany et al. (2024) compared codebooks generated with LLM assistance, where the model either systematically identified themes across a large dataset or refined a human-developed codebook, with codebooks created entirely by human researchers. They found that the LLM-assisted codebooks not only contained a larger number of relevant codes but were also rated higher in comprehensiveness and quality by independent human reviewers. However, many of these studies have not grounded their codebook development in theory, instead adopting a fully inductive approach to code creation, which differs from the theory-guided approach used in the majority of qualitative coding research (Saldaña, 2021) and in much of the related work in the EDM community (e.g., Rupp et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2022; Irgens et al., 2024; Ohmoto et al., 2024).

A fully inductive approach also overlooks the possible perspectives or lenses that an LLM may implicitly apply when creating codes. Even when adopting an inductive approach, many qualitative researchers are concerned about sensitizing concepts—the constructs that influence the initial strategies researchers use when conducting grounded theory research, a methodology focused on developing theory from data rather than on applying existing frameworks (Blumer, 1954; Charmaz, 2006). The goal when beginning this type of work is to start with an open mind rather than an empty one (Corbin and Strauss, 1990). Research suggests that the knowledge base of tools like GPT (and similar LLMs), comprised of the vast collection of open web text data they were trained on, is not neutral or atheoretical (Gallegos et al., 2024), which could influence how an LLM interprets data. If not prompted to consider specific theory, GPT might draw its sensitizing concepts from, for example, the folk theories or widely believed scientific misconceptions present in its training data (Nguyen et al., 2025; Tai et al., 2025).

Although expert human oversight can help to mitigate some of the overt biases that might emerge from the LLM’s training data, (e.g., removing problematic codes, as in Barany et al., 2024), it is more difficult to mitigate other manifestations of bias. For example, missing codes may go unnoticed because experts might not realize what the LLM has overlooked. As another example, it is possible that the LLM may draw from multiple, related theories as opposed to just one, and this implicit decision may go unnoticed by researchers (e.g., considering elements of multiple of the large set of self-regulated learning theories; Panadero, 2017). As such, research is needed to understand how best to guide LLMs to apply appropriate and relevant theoretical lenses for identifying the patterns in the data.

One way to provide such guidance is to explicitly specify the theoretical lenses that should shape the LLM’s focus. In addition to providing prompt-based guardrails to the LLM’s analysis (Rebedea et al., 2023), this approach would also more closely mirror common practices in codebook creation found in the broader literature, where researchers use theory to derive categories and to guide interpretation through conceptual frameworks (Saldaña, 2021). Such practices, when conducted by humans, enhance consistency across studies, support replicability, and contribute to our understanding of how theory can be enacted across diverse contexts (Saldaña, 2021). Building on this tradition, our approach tests whether LLMs (in this case, GPT-4o) can draw on their knowledge base of established learning theories to generate meaningful and theoretically grounded qualitative codebooks.

The Present Study

Whereas prior research has mainly relied on bottom-up, inductive strategies to generate codebooks using LLMs (Barany et al., 2024; De Paoli, 2024; Gao et al., 2024; Katz et al., 2024), this study explores and compares several prompting approaches aimed at producing codes with intentional theoretical alignment. Given that OpenAI’s GPT models have been the most widely studied LLMs in prior research, we employ GPT-4o, the most recent and cost-effective model in the GPT family at the time this study was conducted. We apply these multiple prompting approaches across two theoretical domains: self-regulated learning (SRL) and interest development (ID), both of which are commonly used in EDM research (e.g., Zhang et al., 2022; Zhou and Paquette, 2024). Specifically, we investigate the following research questions:

(RQ1) How effectively can GPT contribute to the qualitative codebook development process when guided by specific learning theories?

(RQ2) What prompting approaches best guide GPT to apply specific theoretical frameworks in collaboration with human researchers during codebook development?

For the SRL context (Study 1), we implemented a three-step process to create a codebook grounded in two foundational SRL theories: Winne and Hadwin (1998) and Zimmerman (2000), both widely used in the learning sciences. First, we prompted GPT-4o to generate a baseline codebook drawing solely from its knowledge base about the two foundational SRL papers, explicitly including full references in the prompt. Second, we provided GPT with both the theoretical frameworks and our data (think-aloud transcripts from several learning contexts) to examine how it applied SRL theory to identify patterns in authentic student behavior. Finally, two human coders reviewed and refined the codebook generated in the second step (cf. Barany et al., 2024), allowing us to assess the outcomes of a collaborative human-AI coding process and the extent of human input needed to produce a usable, theory-aligned codebook.

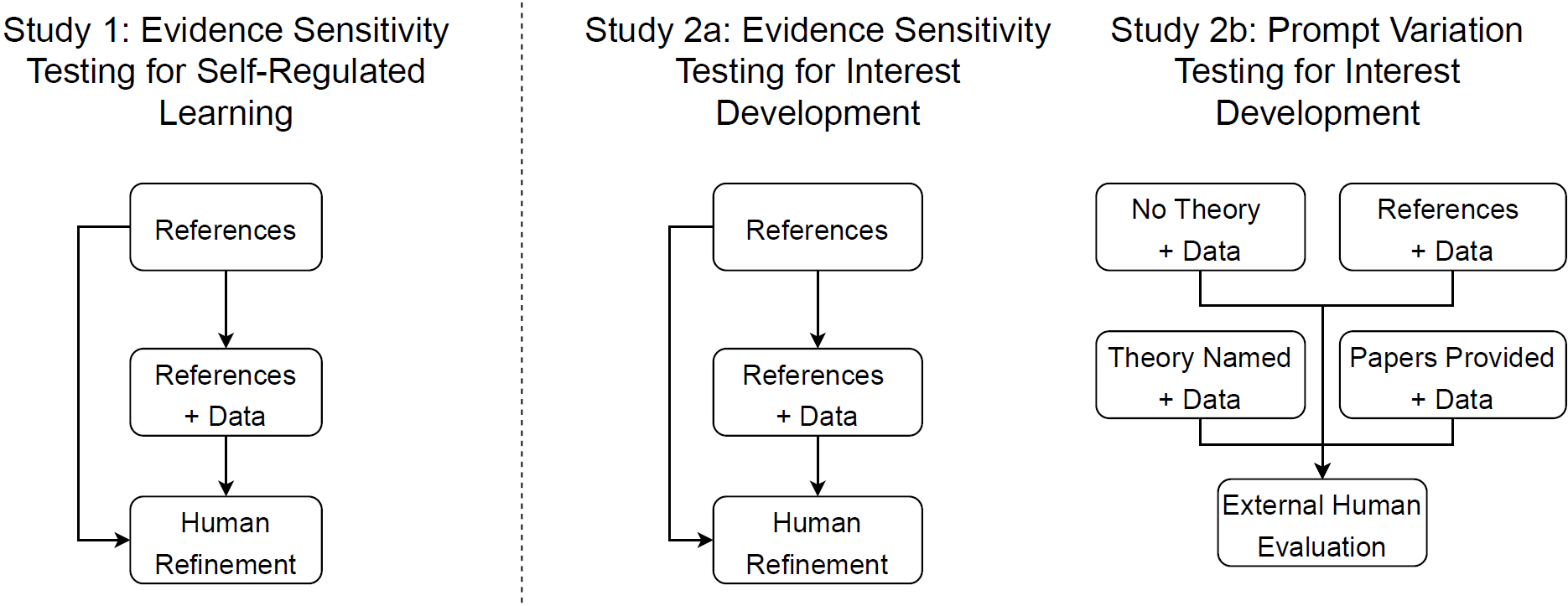

We then attempted to replicate this process in a second context, focusing on Hidi and Renninger’s (2006) four-phase model of ID (Study 2). This framework was chosen because, unlike SRL theories, it operates at a more abstract level, reflecting the many ways interest can manifest and thus posing a potentially greater challenge for GPT. Using the same prompt structure as in the SRL case, we observed that GPT produced theoretically aligned but less practical results. This suggested an opportunity to explore additional prompt engineering strategies to effectively operationalize this theory. In response, we expanded our investigation in this context to explore alternative prompting strategies that might yield more relevant and usable codes. Therefore, Study 2 compares four prompt-engineering strategies to evaluate GPT’s capacity to generate useful and practical, theory-informed codebooks: (1) no explicit reference to theory, replicating the approach used in prior inductive studies; (2) naming the target framework without providing references; (3) supplying a list of references, as in Study 1; and (4) providing the full text of the foundational papers (see Figure 1). By systematically comparing these conditions, we aim to understand how different types of theoretical input influence the constructs generated by GPT and identify which strategies yield the most valid and actionable codebooks. Overall, this work seeks to evaluate GPT’s effectiveness as a collaborator in codebook development when guided by established learning theories and to identify the most effective ways to communicate these frameworks in practice.

LLMs in Qualitative Research

LLMs for Automated Coding

LLMs have been proposed as valuable tools for enhancing qualitative research. Most prior work has demonstrated promising performance on automating coding processes in educational research (e.g., Morgan, 2023; Liu et al., 2025) as well as in other domains (Chew et al., 2023; Kirsten et al., 2024). For instance, Liu et al. (2025) compared GPT-4’s performance across three different contexts. In the first, they coded transcripts of human-human tutoring using three prompting strategies: Zero-shot (no examples), Few-shot (with examples), and Few-shot with context (prompts with examples and context). The study found that Zero-shot prompting was most effective for codes with clear, unambiguous definitions, Few-shot prompting worked better for concrete constructs that still require illustrative examples to clarify their meaning, and Few-shot with context was only beneficial for constructs that explicitly require contextual information. In some cases, however, this added context overwhelmed GPT and reduced performance. These prompting strategies were also tested by the authors on student-written observations while playing an astronomy-focused educational game, and on programming assignments from an introductory computer science course. Across these additional contexts, both Zero-shot and Few-shot approaches showed strong performance for most constructs. Similarly, Morgan (2023) examined GPT’s ability to identify key themes in focus group transcripts from two contexts: first-year graduate students and dual-earner caregivers. They found that GPT performed reasonably well with concrete, descriptive themes but struggled to identify more subtle, interpretive themes. Together, these studies suggest that GPT is well-suited for coding qualitative data involving clearly defined, concrete constructs, but tends to show greater disagreement with human researchers when dealing with constructs that require more interpretive nuance.

Building on this line of inquiry, Borchers et al. (2025) evaluated a multi-agent system designed to code interactions between tutors and students in a virtual environment. Their system included a single-agent coder to simulate individual annotation, a dual-agent discussion module to model inter-annotator dialogue, and a consensus agent responsible for finalizing codes after reviewing both responses. The findings showed that consensus was more easily reached when discussions involved LLMs operating at low temperature with assertive personas, and that both single-agent and consensus outputs demonstrated high agreement with human coding. These findings strengthen the case for the viability and usefulness of incorporating LLMs into qualitative coding processes.

Other work in this area has also focused on analyzing how GPT can assist in analyzing and discussing coding disagreements between researchers (both human-AI and even human-human; Zambrano et al., 2023; López-Fierro et al., 2025). In particular, Zambrano et al. (2023) proposed leveraging the conversational abilities of LLMs (ChatGPT-3.5) not only to automate coding but also to explain its coding decisions and revise coding categories. This process can help researchers evaluate whether their own code definitions and labeling strategies need refinement. Although overall LLM coding performance metrics were not as good as in later work, the authors identified instances where human coders were inconsistent in their labeling, for which GPT was able to offer clarifications to construct definitions and explanations for why disagreements may have occurred. Likewise, López-Fierro et al. (2025) found that even when ChatGPT-4 disagrees with human coders, prompting GPT to explain not only its own rationale but also the potential sources of disagreement provided insights that can complement researchers’ labeling and encourage reflection on the clarity and precision of the construct definitions. Both studies suggest that GPT’s conversational capabilities may offer valuable support for broader aspects of qualitative research, including collaborative reflection, code validation and iteration, and deeper construct understanding.

LLMs for Codebook Development

Emerging studies have demonstrated the potential of human-AI collaboration across multiple qualitative tasks, including resolving ambiguity in human-developed codes (Jiang et al., 2025), revealing researcher positionality (Bialik et al., 2025), and identifying data subsets that may be especially informative for researchers (Schäfer et al., 2025). As LLMs become more integrated into collaborative coding processes, their role is shifting from functioning solely as automated coders to serving as reflective partners. Motivated by LLMs’ ability to use human-created codebooks to inform their decision-making, researchers have proposed frameworks for developing codebooks and conducting thematic analysis in collaboration with LLMs (De Paoli, 2024; Gao et al., 2024; Katz et al., 2024). For example, De Paoli (2024) introduced a workflow using OpenAI’s Application Programming Interface (API) and GPT-3.5 (the latest version at the time) in which human researchers prompt GPT to identify key themes and example sentences in a pre-cleaned dataset, reduce duplicate codes, and generate definitions of those codes. De Paoli demonstrated that GPT could identify key items in two education-related datasets with minimal human intervention, requiring experts only to clean the input and review the output. Gao et al. (2024), also using OpenAI’s API and GPT-3.5, extended this framework to not only leverage GPT for suggesting codes based on data but also to facilitate discussions among multiple human researchers and suggest grouping constructs for overlapping codes. Lastly, Katz et al. (2024) employed an open-source LLM to identify common topics, sentiments, and themes, and then used text embeddings (numerical representations of language) and clustering analysis to group similar utterances. The LLM was then used to generate themes for each cluster, suggesting preliminary codes that were reviewed and refined by human experts to ensure they accurately represented the data and aligned with the research objectives.

To understand which aspects of thematic analysis are best supported by LLMs, Chen et al. (2025) analyzed open coding outcomes produced by five LLM-based approaches and four human coders using a dataset of online chat messages about a mobile learning application. The LLM-based approaches differed in several ways: the type of LLM used (BERT vs. GPT-4o), the method of presenting and coding the data (in chunks vs. line-by-line), and the nature of the requested output (broad themes vs. more specific codes). In none of these approaches did the LLMs receive codebooks or example codes in advance. The authors found that LLMs, across all configurations, were effective at identifying concrete, content-grounded codes. In contrast, human coders excelled at generating codes that captured more interpretive and conversational dynamics (something LLMs struggled with). Similarly, Barany et al. (2024) examined four approaches to codebook development: a fully manual approach, a fully automated approach employing GPT-4, and two hybrid approaches incorporating GPT at specific steps of the codebook development process. In the first hybrid approach, GPT was used to refine a codebook initially developed by human researchers. In the second, GPT generated an initial set of constructs, which were then refined by a human researcher. The authors found that hybrid approaches, whether GPT is involved early or later in the process, produced codebooks that can be more reliably applied even by human coders and rated as higher quality by independent human reviewers.

These codebook development approaches have recently been applied across a range of educational contexts. For example, Wei et al. (2025) used a hybrid method in which GPT-4o generated initial constructs from a large dataset, which were then manually refined to create a codebook to compare in-game written observations from students with high and low situational interest in a Minecraft-based learning environment. The analysis revealed that students with higher situational interest made observations across a broader range of topics, particularly emphasizing scientific content. Similarly, Ruijten-Dodoiu (2025) asked ChatGPT to extract potential codes from student-AI interaction data and then manually validated and refined the themes. While the GPT-generated themes included some inaccuracies, such as a fabricated trend suggesting all students trusted AI, the iterative interaction with GPT ultimately produced useful insights. The refined themes identified key ways that students used AI in their writing: transforming informal text into formal academic language, meeting word count requirements, exploring weaknesses in their own writing, retrieving factual or referenced information, and structuring discussion points. The analysis also highlighted that some students appeared to rely excessively on GPT for completing writing tasks.

Multi-agent systems built on LLMs have also been investigated as tools to conduct thematic analysis. Simon et al. (2025) propose a workflow that automates the process previously carried out through more manual interactions with LLMs by Barany et al. (2024). In this workflow, an orchestrator agent breaks down the overall procedure of thematic analysis into smaller tasks and assigns those tasks to several coding and consensus agents. Each coding agent independently reviews the text data and generates potential themes or codes, much like individual human coders. A consensus agent then compares these outputs, merges similar codes, and resolves disagreements, mirroring the collaborative practices of human research teams. Using this approach, the authors found that a multi-agent system based on Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieved a high level of coding consistency with human experts when performing inductive thematic analysis on a benchmark dataset, particularly for concrete and descriptive themes.

Although hybrid codebooks have proven useful in educational research, most prior approaches (Barany et al., 2024; De Paoli, 2024; Gao et al., 2024; Katz et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025) have used GPT in a primarily inductive fashion, without grounding the theme identification in any theoretical framework. To address this limitation, Ramanathan et al. (2025) iteratively refined prompts using chain-of-thought prompting, applying consistency checks until a theoretically grounded operationalization was achieved. In their approach, theory was manually embedded into the prompt by providing GPT with a human-developed, theory-based codebook. While this represents an important step forward, the optimal method for identifying theoretically grounded constructs remains unclear. For instance, allowing GPT to generate the codebook itself, drawing on both the data and the underlying theory rather than supplying a pre-existing codebook, may lead to more insightful and contextually relevant results.

Research in other areas outside of education also suggests that how the theoretical information is presented to GPT could be important. For example, studies have found that prompting GPT with excessive contextual information or overly detailed instructions can reduce its accuracy in performing the intended task (Koopman and Zuccon, 2023; Peters and Chin-Yee, 2025). Moreover, research suggests that there are specific qualities of scientific write-ups (e.g., the differences in tense, the use of hedges) that may influence the degree to which LLMs generalize to new information (Peters and Chin-Yee, 2025). Therefore, it is possible that LLMs’ ability to generate new codes based on a specific theoretical framework could be influenced by the researchers’ writing style. Finding ways to mitigate such concerns would be an important step in developing prompt-engineering frameworks (see review in Sahoo et al., 2024) that would improve LLMs’ ability to effectively assist in this type of research tasks. To that end, this study explores multiple ways of presenting theoretical frameworks to GPT in order to identify strategies that lead to more practical, relevant, and theoretically aligned codebooks.

Study 1: Developing a Codebook to Investigate Self-Regulated Learning

Theoretical Framework

The first theoretical framework for which we developed codebooks in collaboration with GPT was SRL. Grounded in both information-processing and social-cognitive traditions, various theoretical frameworks have defined SRL as a cyclical and loosely sequenced process that involves a dynamic interplay among cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and emotional components within and across learning episodes, while also being shaped by learner characteristics, task demands, and the social context (Panadero, 2017; Greene et al., 2023). Among these frameworks, Zimmerman’s (2000) cyclical phases model and Winne and Hadwin’s (1998) four-stage model have been especially influential in guiding the development of qualitative codebooks for analyzing SRL behaviors (e.g., Bannert et al., 2014; Hutt et al., 2021; Borchers et al., 2024), making them an important reference point for testing GPT’s capacity to generate theory-based codebooks.

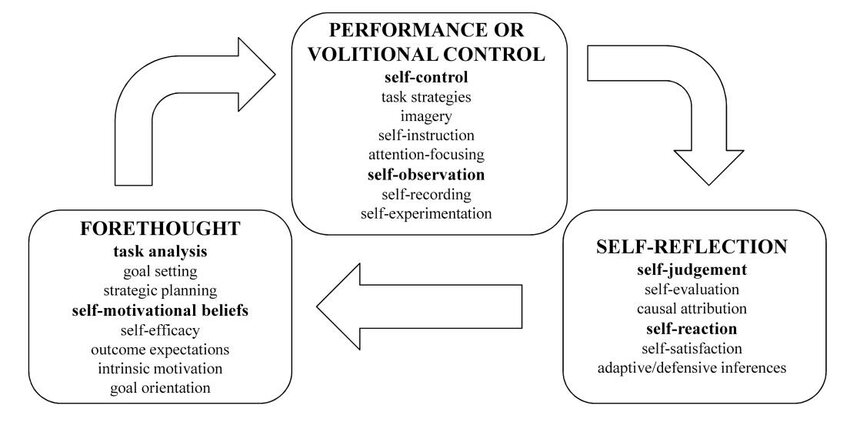

Based on socio-cognitive theories, Zimmerman (2000) describes SRL as three cyclical phases (i.e., forethought, performance, and self-reflection), in which learners analyze a task, execute it, and assess their performance. In the forethought phase, learners set goals and develop strategies, with task analysis and self-motivation as key components. Motivational beliefs such as intrinsic interest or self-efficacy (personal beliefs about one’s abilities) can influence goal-setting behaviors, ultimately impacting the level of difficulty of the goals a learner sets and their commitment to achieving them. In the performance phase, learners engage in two main processes (self-control and self-observation) to ensure the successful execution of their plan. Self-control involves strategies that help learners stay focused on the task and optimize their effort, while self-observation encompasses methods for monitoring their performance and the surrounding conditions. Finally, in the self-reflection phase, learners evaluate their performance against a set of criteria (self-evaluation) to determine whether success or failure is due to internal or external factors. Their level of satisfaction with the outcome (self-satisfaction) and their preferred response style (adaptive-defensive) subsequently influences their future regulatory behaviors (see Figure 2).

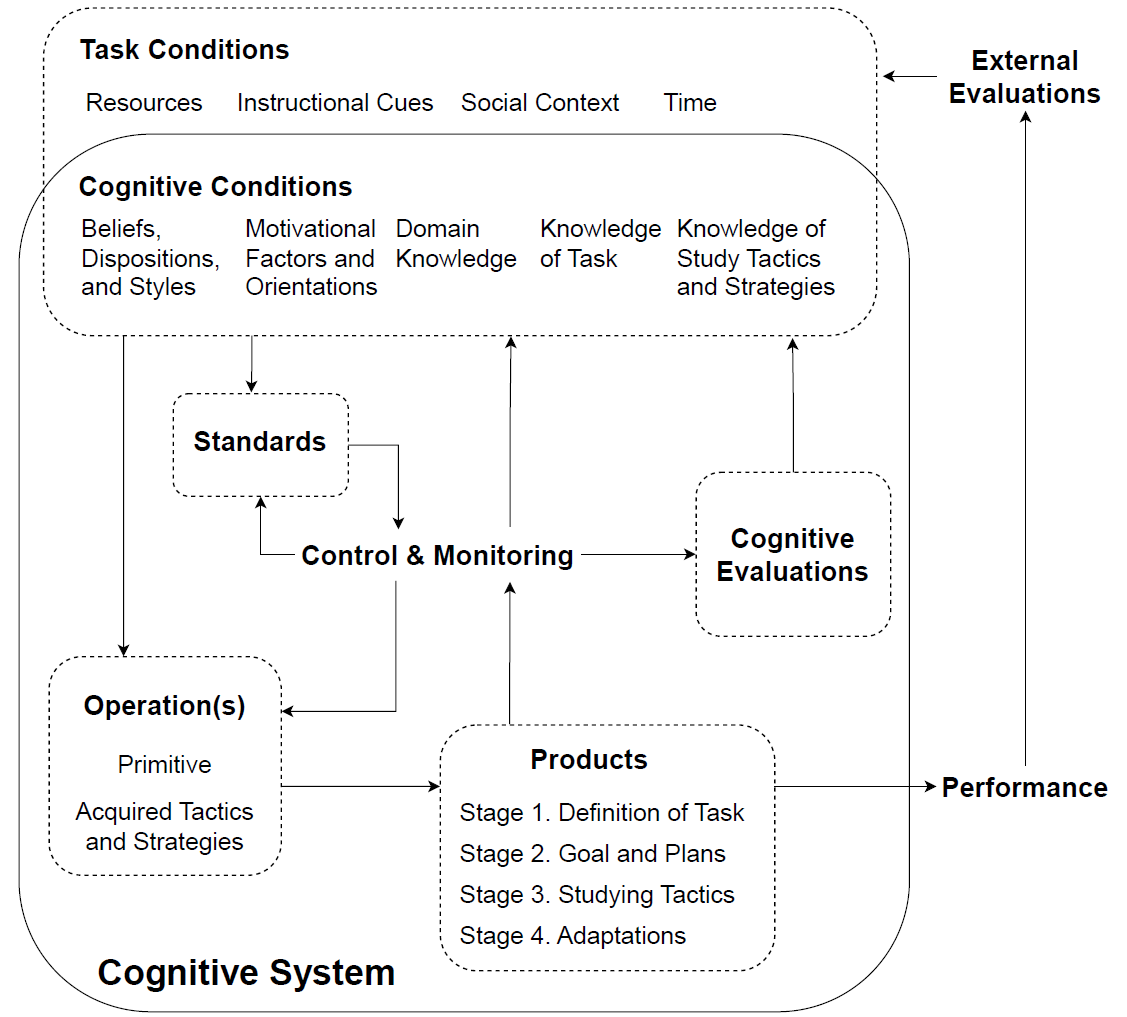

Grounded in information processing theory, Winne and Hadwin (1998) characterize SRL as a process involving four interdependent and recursive stages, in which learners: 1) define the task, 2) set goals and form plans, 3) enact the plans, and 4) reflect on and adapt strategies if goals are not met (Figure 3). Winne and Hadwin (1998) specifically highlight the importance of cognition and metacognition in this process. To describe how learners navigate tasks at each stage, they proposed the COPES model, which outlines five core components involved in self-regulation. According to this model, learners assess task conditions (C), engage in cognitive operations (O) to generate a product (P), and evaluate (E) that product against internal or external standards (S).

Zimmerman’s and Winne and Hadwin’s SRL models share several foundational assumptions about how learners manage their own learning processes. Both frameworks represent SRL as a cyclical and dynamic process in which learners set goals, select and implement strategies, monitor their progress, and adjust behaviors based on feedback. They also emphasize the central role of metacognition (particularly monitoring, self-control, and adaptation) and acknowledge that motivation and contextual factors shape how learners engage with and sustain learning tasks. Despite these shared principles, the models differ in their theoretical grounding and in the emphasis they place on specific SRL components. Zimmerman’s model, rooted in social cognitive theory, organizes SRL into three broad phases (forethought, performance, and self-reflection) and highlights motivational constructs such as self-efficacy, goal orientation, and self-satisfaction. It represents a relatively higher-level account of the processes of SRL, less fine-grained than Winne and Hadwin’s model. In contrast, Winne and Hadwin’s model adopts an information-processing perspective, presenting SRL as a more fine-grained and mechanistic process in which learners regulate their behavior through the interaction of Conditions, Operations, Products, Evaluations, and Standards, offering a more detailed account of how learners interpret, monitor, and respond to task demands in real time.

As a multidimensional construct, SRL encompasses various aspects that GPT can help examine and synthesize. The two selected frameworks capture a wide range of SRL processes, including behavioral, affective, cognitive, and metacognitive components, making them good tests of GPT’s ability to develop a comprehensive codebook. Moreover, both models are now well established in the literature, suggesting that sufficient information on these frameworks is likely included in the training data of GPT. Preliminary checks asking GPT about the theory confirmed that GPT can accurately summarize all the key elements of the model, suggesting it is appropriate for evaluating GPT’s ability to generate theoretically grounded codebooks.

Data Context

To assess GPT’s capacity for suggesting constructs related to SRL, we selected an open dataset that has previously been coded (by humans) and analyzed for SRL using a custom codebook based on the theory by Winne and Hadwin (Borchers et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024a). The dataset consists of think-aloud transcripts from students working within three intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs). These systems covered topics in stoichiometry (Stoichiometry Tutor, McLaren et al., 2006; and ORCCA, King et al., 2022) and formal logic (Logic Tutor, Zhang et al., 2024b). Fourteen undergraduate students and one graduate student participated in the study between February and November 2023 in the United States. The participants’ demographics were 40% white, 47% Asian, and 13% multi- or biracial. Ten students were recruited from a private research university and participated in person, while five students from a large public liberal arts university participated remotely via Zoom.

Students participated in a 45-60 minute session, where they were assigned to one of three ITSs. Each system had at least five students, with six students working on both stoichiometry ITSs after completing one early. The session began with a demographic questionnaire, followed by a pre-recorded introductory video on the assigned ITS, with an opportunity to ask questions afterward. For Logic Tutor, students were also given the option to skim and ask questions about articles on formal logic. After becoming familiar with the tutoring software, students received a brief demonstration and an introduction to the think-aloud method. They then began working on the tutor problems at their own pace for up to 20 minutes while thinking aloud, with occasional reminders from the experiment conductor to keep speaking. The problems were matched in difficulty across the ITSs. The stoichiometry tutors covered mole and gram conversion and stoichiometric conversion (four problems each), while the Logic Tutor focused on simplifying and transforming logical expressions (seven and four problems, respectively). The data set includes a total of 955 utterances transcribed using Whisper, which were segmented based on logged interface interactions in the tutoring systems (see Zhang et al., 2024b). Log data and anonymized synchronized think-aloud transcripts are available upon request for Stoichiometry Tutor and ORCCA at https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=5371 and for the Logic Tutor at https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=5820.

GPT-based Codebook Development

To create the SRL codebook, we employed a three-step process. In the first step, we used GPT to generate a codebook based solely on GPT’s knowledge of foundational theory papers (i.e., Winne and Hadwin, 1998; Zimmerman, 2000) which inspired qualitative coding in past papers involving this data set (Borchers et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024a; 2024b). In the second step, in addition to the theory papers, we provided GPT with data intended to be analyzed within the SRL framework. In the final step, two human coders reviewed and refined the codebook generated in the second one, merging overlapping constructs and excluding constructs that the coders found challenging to identify from the data (cf. Weston et al., 2001; Barany et al., 2024).

When prompting GPT, we used GPT-4o (version gpt-4o-2024-08-06) via OpenAI’s GPT API. Given the stochastic nature of GPT, which may generate different results for equivalent prompts, the temperature parameter was set to 0—a standard practice in this type of research, (e.g., Barany et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025)—and each prompt was run three times to verify consistency across iterations (as in Wang et al., 2022). We conducted several rounds of prompt modifications to guide the model in generating consistent and reliable outputs, following the prompt engineering framework proposed by Giray (2023). This process began with a broad prompt asking GPT to develop a codebook for SRL. Then, multiple variations were tested, and iterative adjustments were made to add specificity and contextual details relevant to this codebook development. The prompts presented here are the final versions obtained after the prompt engineering process.

Step 1: Prompting GPT with Theory Paper References

In the first step (Theory-only), we asked GPT to consider two foundational SRL theory papers (Winne and Hadwin, 1998; Zimmerman, 2000). The prompt shown below was given to GPT as both the system and user message. In the API, the system message defines the assistant’s behavior, tone, and guiding context and the user message provides the specific question or instruction to which the assistant responds.

System/User Message:

You are an expert qualitative researcher in self-regulated learning. Please create a codebook for analyzing students’ think-aloud transcripts considering the following papers:

- Winne, P.H. and Hadwin, A.F. 1998. Studying as Self-Regulated Learning. Metacognition in Educational Theory and Practice. (1998), 277–304.

- Zimmerman, B.J. 2000. Attaining Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Perspective. Handbook of Self-Regulation. 13–39.

Each round of the prompt generates a codebook containing constructs along with their definitions and (synthetic) examples. Two researchers (the 1st and 2nd author) consolidated the codebook by considering all constructs that appeared in any of the three runs. Specifically, constructs with similar names and definitions across multiple rounds were treated as the same (e.g., Self-Monitoring and Self-Observation). Constructs that appeared similar but were not clearly identical for both human researchers (e.g., Planning versus Goal Setting and Monitoring versus Evaluation) were not merged and were included in the codebook as individual and separate constructs.

Step 2: Prompting GPT using both Theory Papers and Data:

In the second step (Theory+Data), we incorporated student data into GPT’s prompting. We retained the same system message used in the Theory-only approach but modified the user message (shown below) to include the dataset. The entire dataset was provided within a single prompt, with each utterance separated by a line break. This formatting allowed GPT to select specific utterances as examples for constructing the codebook.

User Message:

As a qualitative researcher, you can refine constructs proposed in previous theories and suggest new constructs by considering the transcripts that you analyze. Please refine this codebook considering the following transcripts: [FULL DATASET]

In line with Step 1, authors 1 and 2 evaluated construct overlap across all three runs, consolidating all the generated constructs into a single codebook. Constructs that were similar but not clearly identical were again not merged.

Step 3: Final Human Refinement

In the third step (Human Refinement), the 1st and 2nd authors evaluated the specificity (the extent to which a construct is distinct and clearly distinguishable from other related concepts) and applicability (the extent to which a construct can be accurately identified in the data) of the definitions and examples for all constructs obtained in the previous steps. Constructs that did not match the context of the data or included example sentences that did not align with the construct’s definition were filtered out. For example, Imitation was defined by GPT in Step 1 as “observing and imitating the strategies or behaviors of others,” but no such instances were found in the data (as indicated by its absence in Step 2), and it was therefore excluded. No hallucinations (i.e., example sentences created by GPT and not present in the data) were found in this study, but if suitable examples could not be identified in the data, the construct was excluded. Constructs that had similar definitions or overlapping examples but were not clearly identical (e.g., Planning versus Goal Setting and Monitoring versus Evaluation) were collapsed if both researchers agreed they should be combined; all others remained as generated by GPT. Additionally, constructs that were a subset of another construct also proposed by GPT were collapsed into the broader construct if this broader construct was concrete enough and easy to observe in the data. For instance, the construct Task Understanding, defined as correct task comprehension, was collapsed into a broader but comparable construct also in the codebook, Understanding the Task, defined as the process of trying to understand the task. These approaches aligned with existing practices for code refinement in qualitative research (e.g., Strauss, 1987). Given that the primary goal of the study was to evaluate the outcomes of using GPT for codebook development, rather than to assess the researchers’ ability to propose theoretically grounded constructs, no additional constructs beyond those suggested by GPT were added by the researchers.

Results

Step 1: Prompting GPT with Theory Paper References without Providing Data

As Table 1 shows, the codebook suggested by GPT based on the SRL foundational theory papers accurately represents most of the key elements of both SRL theories, indicating that the model’s knowledge base includes appropriate and accurate representations of these theoretical frameworks. GPT proposed constructs that capture all the components across all three phases of Zimmerman’s cyclical self-regulatory model. For Zimmerman’s forethought phase, both the task analysis and self-motivation components were represented by the constructs Goal Setting, Strategic Planning, Self-Efficacy, Intrinsic Motivation, and Task Value. Similarly, Zimmerman’s performance phase, which includes self-control and self-observation, was reflected by the constructs Strategy Use, Resource Management, Adaptive Inferences, Task Monitoring, Self-Monitoring, and Metacognitive Awareness. Finally, the self-reflection phase (self-judgment and self-reaction) was represented by the constructs Reflective Thinking, Adaptive Inferences, Self-Evaluation, and Outcome Evaluation.

|

Step 1: Theory References |

Step 2: Theory + Data |

Step 3: Human Refinement |

|---|---|---|

|

Understanding the Task Task Understanding |

Understanding the Task |

|

|

Goal Setting Strategic Planning |

Goal Setting Strategic Planning |

Planning & Goal Setting |

|

Self-Evaluation Outcome Evaluation |

Error Identification Outcome Evaluation Process Evaluation |

Error Identification |

|

Self-Monitoring Task Monitoring Metacognitive Awareness Reflective Thinking |

Monitoring |

Monitoring |

|

Strategy Use |

Systematic Strategy |

Strategy Use |

|

Adaptive Inferences |

Strategy Adjustment |

Strategy Adjustment |

|

Seeking Help |

Seeking Help |

Help-seeking |

|

Resource Management |

||

|

Self-Efficacy |

Emotional Regulation Self-Efficacy |

Emotional Regulation & Perseverance |

|

Frustration |

Frustration and Self-Doubt |

|

|

Calculation & Conceptual Understanding |

Domain Knowledge Recall |

|

|

Trial and Error |

Trial and Error |

|

|

Intrinsic Motivation |

||

|

Physical Environment |

||

|

Social Environment |

||

|

Imitation |

||

|

Task Value |

Similarly, GPT’s codebook contained constructs for three of the four phases of Winne & Hadwin’s SRL model: set goals and form plans, enact the plans, and reflect and adapt strategies when goals are not met) Only the task definition phase, which occurs before goal setting and planning, is not directly represented in the codebook. That said, Goal Setting and Strategic Planning necessitate a task definition, and it is possible that differentiating between the two would be hard to operationalize.

Although Step 1 suggestions provided good coverage of the different phases of the SRL theories, many of the codes suggested by GPT show substantial overlap with one another, even when they ostensibly cover different phases of SRL. For instance, constructs such as Self-Monitoring, Task Monitoring, Reflective Thinking, and Metacognitive Awareness are conceptually distinct, but may manifest in similar ways. For example, the similarity between the examples like “I think I understand this part, but I’m not sure about the next section” (GPT’s example for Self-Monitoring) and “Next time, I should try a different strategy for better results” (GPT’s example for Reflective Thinking) made it difficult to consistently differentiate between these codes. As will be discussed in the section on Step 3 (below), such codes were collapsed prior to further analysis.

Another concern about the Step 1 codebook was related to the applicability of several codes to this particular data set. For example, constructs like Imitation and Social Environment are important components of SRL models, but their applicability is highly limited in the current data set, where students worked individually within the learning platform and while producing data through a think-aloud protocol. In this context, students were not given opportunities to produce data connected to these constructs. As a result, synthetic examples suggested by GPT for these constructs (e.g., “I noticed my classmate uses flashcards, so I will try that too”) were not plausible. Hypothetically, students could have referred to past experiences involving others (e.g., strategies they copied from a teacher or classmate). However, our data showed no such references, indicating that neither construct is appropriate for coding this specific data set and context.

Step 2: Prompting GPT using both Theory Paper References and Data

We next tested GPT’s sensitivity to the SRL study’s data to determine how that might influence the codebook generation process. When provided with the data, GPT produced a codebook that was more complete (see Table 1), capturing elements from all phases of both theoretical models. This is an improvement over the Step 1 (Theory-only), as the Step 2 (Theory+Data) codebook incorporated Winne & Hadwin’s phase of task definition, the only phase of their SRL model missing from the Step 1 approach. In Step 2, GPT differentiated between the process of attempting to grasp the task (Understanding the Task), attaining accurate task comprehension (Task Understanding), and the forethought phases focused on Goal Setting and Strategic Planning. All other stages from both Zimmerman’s and Winne and Hadwin’s SRL models were represented in the Theory+Data codebook.

GPT also produced fewer overlapping constructs than it did in Step 1. For example, the Theory+Data codebook included a code called Monitoring, which was illustrated using the same examples from the four overlapping constructs in the Theory-only codebook (Self-Monitoring, Task Monitoring, Reflective Thinking, and Metacognitive Awareness). This suggests that the Step 2 codebook may have more effectively identified and labelled these examples as a single construct.

GPT also introduced a new construct, Error Identification, which was not present in Step 1. This construct captures instances where students explicitly recognize a previous mistake or incorrect answer (e.g., “And now I just realized that I should have done all the equations first.”). Although this construct does seem to be a type of Monitoring, the specificity of Error Identification made it easier to differentiate from other types of monitoring behaviors.

Furthermore, GPT provided codes in Step 2 that better differentiated between different types of behaviors in the performance (Zimmerman) or enactment (Winne & Hadwin) phases of the SRL models. GPT suggested codes like Trial-and-Error (e.g., “I’m going to submit this guess now”), differentiating from Systematic Strategy (e.g., “Let’s make some notes that we don’t forget anything like the 6 before.”). GPT also identified instances where students used Calculations & Conceptual Understanding while solving tasks (e.g., “Let’s use inverse absorption to simplify this expression”). This additional code could help identify cases where conceptual knowledge guides students’ strategies and processes.

Finally, constructs that were relevant to the theory but absent from the data (see discussion in Section 3.4.1), were appropriately filtered out by GPT once the data was available. For example, Imitation and Social Environment, which emerged in Step 1, did not appear in Step Two. Several motivational constructs were also either excluded or replaced with more specific constructs such as Frustration (e.g., “This is driving me crazy with all the denominators”) and Emotional Regulation & Perseverance (e.g., “This is frustrating, but I’ll keep trying.”). As a result, the Step 2 codebook showed better alignment with the students’ think-aloud data.

Step 3: Final Human Refinement

The Step 2 (Theory+Data) codebook improved upon the Step 1 codebook by reducing the number of overlapping constructs, enhancing the specificity of proposed constructs, and providing constructs that were more relevant (sensitive) to the think-aloud data. However, further human refinement was still warranted. This refinement process resulted in a final codebook consisting of eleven constructs. Definitions and examples for each construct are presented in Table 2.

In some cases, codes were simply renamed and refined. For example, GPT defined Calculation & Conceptual Understanding as the “explicit use of domain-specific knowledge or mental calculation to understand and solve the task,” and provided the example, “Let’s use inverse absorption to simplify this expression.” Given concerns about GPT’s ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect uses of technical terms (e.g., “absorption,” “Avogadro’s number,” or “De Morgan’s law”), human researchers refined and renamed this construct Domain Knowledge Recall.

In many cases, codes generated by GPT were merged into a single category when the examples were too close to provide a meaningful distinction. For instance, GPT distinguished between students working towards understanding (Understanding the Task) and achieving understanding (Task Understanding). Example sentences for the former included “Let’s figure out how many hydrogen atoms are in a millimole of water, H2O molecules” while examples for the latter included “Let’s figure out how many CO2s there are in a single millimole of C2H6.” Although human experts with access to the data could discern whether students understood the task correctly, this approach may not be practical for large datasets where full human inspection is infeasible. Therefore, the researchers merged them into a single category: Understanding the Task.

Code & Definition | Example Utterances from the Data |

|---|---|

Understanding the Task: Specific mental processes used to understand the task. | "Let’s figure out how many hydrogen atoms are in the millimole of water" |

Planning & Goal Setting: Students outline their goals, objectives, or strategy before engaging in the planned action. | "I’m going to first handle the negation and then move to the next part." |

Error Identification: Students detect an error in the process or solution of the task | "So I guess the 25m I wrote there is not correct." OR "Oh, I missed a negation, let me fix that." |

Monitoring: Checking understanding or progress during the task. | "Am I reading the statement again and see if I forgot anything?" |

Strategy Use and Execution: Applying systematic steps to solve the problem. | "I’m going to multiply this by Avogadro’s number." |

Strategy Adjustment: Actions taken to correct or adjust strategies based on monitoring. | "Let's make some notes that we don't forget anything like the 6 before." OR "So I'm going to do it the safe way." |

Help-seeking: Use of hints or external resources when the student is unsure or stuck. | "OK, I’m asking for a hint now." OR "Let’s get the second hint." |

Emotional Regulation & Perseverance: Perseverance and determination despite difficulty, ambiguity, or frustration | "This is frustrating, but I’ll keep trying." OR "I’m almost there, just one more step!" |

Frustration & Self-doubt: Frustration with repeated errors or setbacks. | "This is driving me crazy for all the denominators." |

Domain Knowledge Recall: Statements referring to subject-specific concepts, equations, or principles. | “Let’s use inverse absorption to simplify this expression.” |

Trial & Error: Experimenting with various rules or strategies when uncertain. | “I'm going to submit this guess now.” |

Similarly, GPT proposed Process Evaluation and Outcome Evaluation as distinct additional constructs to capture students’ reflections on their strategies and outcomes. However, the example sentences provided for these constructs were repeated for Error Identification (e.g., “And now I just realized that I should have done all the equations first” and “The result is no 100,000”), suggesting that all three may be capturing a similar underlying behavior. Consequently, during human refinement, the constructs were consolidated under the broader and more clearly defined construct Error Identification. Several other codes were also merged for the same reason. For instance, the examples given for Strategic Planning (e.g., “So I should determine the amount of C6H1206 in mole”) were not distinguishable from those given for Goal Setting (e.g., “Let's create the formula and just sum up what we've learned so far”). Even though construct definitions appeared distinct, human inspection found many data examples that could fit both codes, (e.g., “We need to apply absorption and simplify this part first.”). Since both codes were also theoretically similar (i.e., both belong to either Zimmerman’s forethought phase or Winne & Hadwin’s planning stage), they were merged into Planning & Goal Setting. Monitoring and Evaluation, Error Identification and Outcome Evaluation, and Self-Efficacy and Emotional Regulation also showed substantial overlaps in their definitions, examples, and theoretical mappings, and were therefore merged into Monitoring & Evaluation, Error Identification, and Emotional Regulation & Perseverance, respectively. In sum, while the use of GPT in Step 1 and Step 2 shows the potential of the tool for supporting theory and data-relevant codebook development, human review remains essential for code merging and codebook refinement.

Study 2: Developing a Codebook to Investigate Interest Development

Theoretical Framework

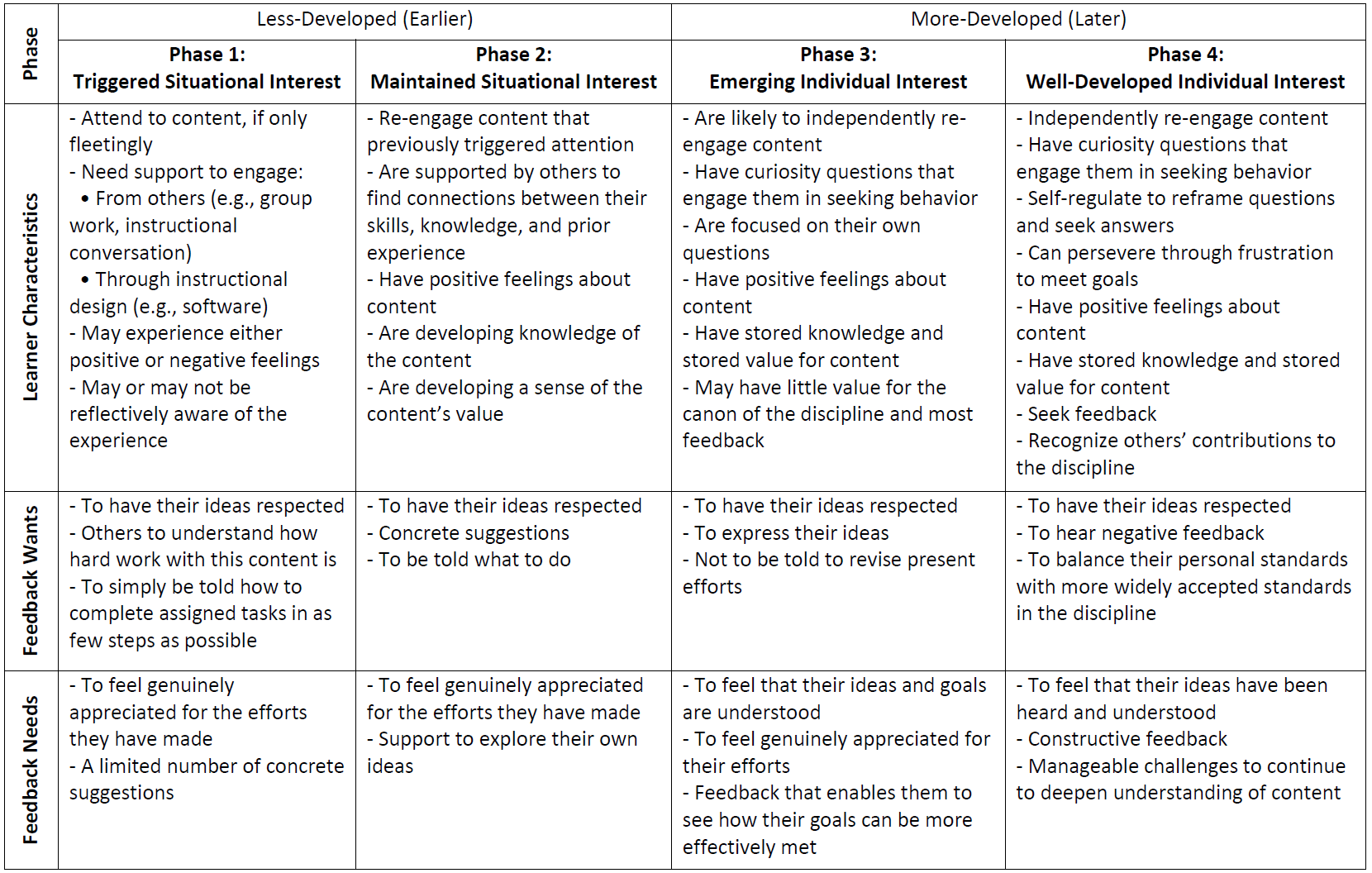

The second theoretical framework that informed GPT-assisted codebook development was student interest development. In particular, we focused on Hidi & Renninger’s Four-Phase Model of Interest Development (ID; Hidi and Renninger, 2006). This model outlines a progression of increasingly personal and sustained interest states: (1) triggered situational interest, a brief initial spark often stimulated by the learning environment; (2) maintained situational interest, involving prolonged engagement still influenced by external factors; (3) emerging individual interest, where learners begin forming personal connections and actively seeking out the topic; and (4) well-developed individual interest, characterized by long-term, self-sustained engagement, even in the face of challenges (see Figure 4).

In this framework, interest is not a fixed learner trait, but a dynamic, developmental process shaped by both environmental supports and individual motivation. In the early stages, external factors, such as engaging activities, novelty, and social interactions, play a critical role in sparking and sustaining interest. As students acquire more knowledge in a given domain, interest is internalized, and learners demonstrate greater autonomy, persistence, and depth of engagement (Hidi and Renninger, 2006). The model further highlights how cognitive, emotional, and behavioral indicators can signal different phases of interest development, ranging from momentary curiosity to sustained, meaningful engagement with a domain—often characterized by increased personal relevance, reflective thinking, and self-directed exploration.

Hidi & Renninger’s model provides an important test case as it is now well established in the literature. It has also inspired the development of several instruments related to interest development, including Linnenbrink-Garcia’s widely-used survey of situational interest (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2010). Given its extensive recognition in the literature, we expect that sufficient data on this framework exists within the LLM training set. As with SRL models, preliminary checks confirmed that GPT can accurately summarize the key elements of the framework.

The four-phase model has seen widespread use in empirical research, in part because its high-level approach can be adapted to many settings. Although some scholars have noted that its conceptualization of interest development may appear broad or linear in certain contexts (e.g., Azevedo, 2011), this generality also allows for broad applicability. As a result, a codebook based on this theory must go beyond simply categorizing the four main stages of interest development. To generate deeper theoretical insights, the codebook must provide more detailed operationalizations that are suited to specific contexts (e.g., Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2010). This adds complexity to GPT’s task, requiring it to generate constructs, definitions, and examples that are not only theoretically grounded but also relevant to analysis in specific contexts. Consequently, this framework serves as a useful test case for assessing GPT’s ability to move beyond broad theoretical categories and produce nuanced, applicable codebooks.

Data Context

To evaluate GPT’s ability to suggest theoretically-driven constructs related to interest development, we analyzed 144 interview transcripts from 14 middle-school students who participated in a 5-day (15 hour) summer camp held in the northeastern United States in 2024 as part of the WHIMC project (Lane et al., 2022). The WHIMC project leverages Minecraft’s Java Edition to immerse learners in simulation environments where they can explore hypothetical astronomy scenarios that address “What-if” questions, such as “What if Earth had no moon?” or “What if Earth was orbiting a colder sun?”. Students differed in terms of gender (ten male, three female, and one non-binary) and race/ethnicity (eight White Americans, two Asian Americans, one European, and three individuals who preferred not to disclose). Participation in the research was entirely voluntary, with consent and assent obtained from parents and participants, respectively. Interviews were collected using an open-source app called Quick Red Fox (Hutt et al., 2022), which enables researchers to conduct Data-Driven Classroom Interviews (DDCIs; Baker et al., 2024) in the moment, as triggered by specific student actions that have been identified as potential indicators of interest, disinterest, or struggle. DDCIs allow interviewers to capture key moments in students’ interest development, resulting in a rich and timely dataset of student reflections that we then use to evaluate GPT’s codebook development capabilities. This data was provided to our team by members of the WHIMC research team.

Replication of Prompts Proposed for Study 1

We replicated the methods from Study 1, only modifying the prompt by changing the theoretical framework (ID instead of SRL) and the corresponding reference. We applied the same three-step process, generating codebooks using only the theoretical papers (Step 1), then with both the theoretical papers and the data (Step 2), and then through human refinement (Step 3).

In Step 1 (Theory Only), GPT generated a codebook that produced codes that mirrored the four phases of the ID model as the primary constructs for the codebook (Triggered Situational Interest, Maintained Situational Interest, Emerging Individual Interest, and Well-Developed Individual Interest; see Table 3). These four codes were proposed consistently across all three iterations. In addition, GPT also consistently identified the construct External Influences, defined as “factors outside the individual that influence interest development, such as teachers, peers, resources, and environment,” which represents broader contextual elements that can shape any of the four stages. Finally, GPT suggested constructs like Internal Motivations, Emotional Responses, and Barriers to Interest Development, though each appeared only once across the different runs.

|

Step 1: Theory References |

Step 2: Theory Papers + Data |

Step 3: Human Refinement |

|---|---|---|

|

Triggered Situational Interest |

Triggered Situational Interest Engagement |

Theoretical Phases |

|

Maintained Situational Interest |

Maintained Situational Interest Engagement |

|

|

Emerging Individual Interest |

Emerging Individual Interest Engagement |

|

|

Well-Developed Individual Interest |

Well-Developed Individual Interest Engagement |

|

|

Internal Motivations |

||

|

External Influences |

Peer Interaction |

Peer Interaction |

|

Situational Interest Support |

||

|

Instructor Interaction |

||

|

Social Challenges |

||

|

Emotional Responses |

Situational Interest Emotion |

Positive Emotion |

|

Individual Interest Emotion |

||

|

Emotional Challenges |

Negative Emotion |

|

|

Barriers to Interest Development |

Technical Challenges |

Technical Issues |

|

Task Challenge |

Cognitive Challenges |

|

|

Resources |

||

|

Situational Interest Stimulus |

Minecraft Environment Stimulus |

|

|

Environmental Factors |

||

|

Task Novelty |

||

|

Knowledge |

Knowledge |

|

|

Reflection |

Reflection |

|

|

Task Relevance |

Perceived Value |

|

|

Strategy Use |

Problem Solving |

|

|

Learning |

Learning |

Although these constructs align with the theoretical model, human reviewers found them to be too broad to effectively discriminate among different phenomena in the data. For example, GPT defined Maintained Situational Interest in a way that mirrors the theoretical literature (i.e., as characterized by “continued engagement with the subject matter over time, positive feedback or reinforcement from peers, teachers, or activities, and expressions of enjoyment or satisfaction from ongoing activities”). However, a code that reflects a broad, complex phase, characterized by considerable duration, is inappropriate for labeling an individual utterance in a student interview. A more useful operationalization of this construct would likely require breaking it down into more granular subcodes (e.g., Positive Reinforcement, Enjoyment or Satisfaction). Similarly, constructs such as Emotional Responses or Barriers to Interest Development, which emerged only once as a code across the runs on different data subsets, would benefit from further refinement to distinguish between positive and negative emotions or to identify specific challenges that may hinder students’ interest development.

In Step 2 (Theory+Data), GPT produced a codebook that was more expansive, including more narrow codes that still aligned with the theoretical model. For example, components from the earlier definition of Maintained Situational Interest, such as peer and instructor interactions and expressions of enjoyment or satisfaction, were further differentiated into distinct constructs: Peer Interaction, Instructor Interaction, Interest Emotions, Task Novelty, and Task Relevance. Similarly, the broader construct of Emotional Responses was refined into more specific categories, such as Situational Interest Emotions, Individual Interest Emotions, and Emotional Challenges. Barriers to Interest Development were also subdivided into more specific constructs, including Emotional, Social, Technical, and Task-related Challenges. Notably, the construct Internal Motivations was not suggested by GPT in this second step, as it did not identify an explicit example of it in the data.

Although many of the constructs generated in Step 2 were more practical than those in the original theory-only codebook, some still closely mirrored the theoretical interest development model without fully accounting for the practical challenges of identifying them in the dataset. For instance, Situational Interest Emotion and Individual Interest Emotion both refer to positive emotions or enjoyment associated with different phases of interest. While these distinctions are theoretically meaningful, they lack discriminant validity, since the positive emotions experienced during each are unlikely to differ at the level of a student utterance. The same concern emerged for Situational Interest Engagement and Individual Interest Engagement which are similarly difficult (if not impossible) to reliably distinguish in the context of interview transcripts.

The Step 2 codebook showed other forms of conceptual redundancy, with considerable overlap between constructs like Situational Interest Stimulus, Task Novelty, and Environmental Factors, all of which refer to aspects of the Minecraft environment that could trigger situational interest. Human reviewers determined these constructs were not sufficiently distinct and merged them to form the construct Minecraft Environment Stimulus in Step Three.

Other constructs from the Step 2 codebook offered finer-grained distinctions than the Step 1 codebook, but some still had validity issues. For example, the Social Interactions code proposed in Step 1 aligned with Step 2 codes that appeared more specific (i.e., Peer Interaction, Instructor Interaction, and Social Challenges) but GPT assigned examples to these Step 2 codes that were misleading. For instance, the construct Social Challenges, which appeared in only one run, included a question asked by the interviewer (i.e., “Your brother doesn’t like the sinking gravel?”) that did not refer to any conflict. In fact, the student responded that their brother was helping “a lot,” and corresponded to a moment of collaboration rather than challenge. Similarly, examples for Instructor Interaction include sentences referring to interviewer questions (e.g., “What are you working on? What did you just do?”) instead of referring to any previous interaction or comment about the instructor. This indicates that although GPT suggests a division of social constructs into Peer Interaction, Instructor Interaction, and Social Challenges, which may be worth coding separately in some research contexts, it struggles to identify actual instances in the data that meaningfully differentiate these categories.

As with the SRL codebook, Step 3 involved a human review to consolidate the codes generated in Steps 1 and 2 into a single, refined codebook. In this case, the need for human oversight was even more pronounced. Key issues included constructs that were too broad to be easily operationalized, as well as the absence of important constructs that were clearly observable in the data and feasible to define but were not suggested by GPT. For example, although we observed multiple instances of students demonstrating scientific reasoning (an indicator of Emerging or Well-Developed Individual Interest) GPT did not suggest such a code. In response to these concerns about the quality and operationalization of GPT-generated codes, we expanded our prompting strategies to explore which techniques might improve GPT’s ability to generate usable constructs for qualitative coding in this context.

Evaluation of Multiple Prompts for GPT-based Codebook Development

Prompt Engineering

We compared four approaches to codebook development using GPT-4o via OpenAI’s GPT API (version gpt-4o-2024-11-20) with the temperature parameter set to 0 to reduce randomness and enhance consistency in GPT’s output. Specifically, we examined different possible ways to influence the theoretical lens that GPT uses to develop qualitative codes for interpreting student interview data. Again following the prompt engineering framework proposed by Giray (2023), we began with a broad prompt asking GPT to develop a codebook capturing emerging themes tied to student interests in the interview transcripts. Then, multiple variations of the prompt were tested, and iterative adjustments were made to add specificity and contextual details relevant to this codebook development before the final version was selected. As Table 4 shows, we used both a system message (high-level directive that defines GPT’s behavior and role) and a user message (task-specific instructions) with each approach. Only minor modifications (those necessary for changing the method) were made across approaches. Places where those prompts were modified from one approach to the next are marked in Table 4, and the variable text is shown in Tables 5 and 6.

Stage | Prompt |

|---|---|

System Message | You are an experienced qualitative researcher with decades of expertise studying science interest development in middle school students. Your goal is to analyze interview transcripts of middle school students playing a version of Minecraft that is designed to help them learn about science and astronomy. To achieve this, you will create a codebook [THEORETICAL/ATHEORETICAL APPROACH TEXT, SEE TABLE 5]. Please generate codes that emerge within a context like the one we are studying here. |

User Message | Your task is to: 1. Identify themes and codes focusing exclusively on direct, explicit evidence from the students’ responses. 2. Propose an actionable and structured codebook that includes: - Code names and definitions: Concise, clear labels and explanations of each code. - Examples from the data: Specific quotes or excerpts illustrating each code. 3. Provide 3 examples for each code. [USER MESSAGE APPROACH TEXT, SEE TABLE 6] **Qualitative Data Excerpts:** Analyze the following data excerpts to inform the codebook development: **Data Excerpts Start:** [Insert data excerpts here] **[Data Excerpts End]** Your reply should be the completed codebook, structured with code names, definitions, and examples, ready for immediate use in qualitative analysis. |

Approach | System Message Addition |

|---|---|

1) Atheoretical | grounded in the qualitative data. |

2-4) Theory-based Approaches | grounded in both theoretical frameworks on interest development and the qualitative data itself. Please do not just use the major categories of the theoretical frameworks. |

Approach | User Message Addition |

|---|---|

2) Theory Named | **Important Note:** I will provide qualitative data excerpts, which will be labeled with a starting identifier (e.g., **'Data Excerpts Start:'**) and an ending identifier (e.g., **'[Data Excerpts End]'**) for clarity. Consider the theoretical and empirical foundation of Hidi and Renninger's 4-phase model of interest development as the basis for developing the codebook. |

3) Full References Given | **Important Note:** I will provide qualitative data excerpts, which will be labeled with a starting identifier (e.g., **'Data Excerpts Start:'**) and an ending identifier (e.g., **'[Data Excerpts End]'**) for clarity. Consider the following articles as the theoretical foundation for developing the codebook: - Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111-127. - Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Durik, A.M., Conley, A.M., Barron, K.E., Tauer, J.M., Karabenick, S.A., & Harackiewicz, J.M. (2010). Measuring situational interest in academic domains. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(4), 647-671. |

4) Papers Provided | **Important Notes:** 1. I will provide the theoretical frame- works in the form of full-text articles. Each article will be clearly labeled with a starting identifier (e.g., **'Article 1:'**) and an ending identifier (e.g., **'[End of Article 1]'**) to help you distinguish between them. 2. I will also provide qualitative data excerpts, which will be similarly labeled with a starting identifier (e.g., **'Data Excerpts Start:'**) and an ending identifier (e.g., **'[Data Excerpts End]'**) for clarity. **Theoretical Lenses:** Consider the following articles as the theoretical foundation for developing the codebook: |

The four approaches differed in whether and how GPT was instructed to integrate a theoretical lens into its codebook development approach. In all four approaches, GPT was prompted to consider student-produced data, delivered iteratively in three batches, each of which contained 48 student interviews. The data was segmented this way due to the size of the dataset and the maximum token for a single prompt sent to GPT (128,000). Delimiters were added to mark the beginning and end of the data so that GPT could distinguish between the prompt instructions and the student interviews. Additional delimiters identified the speaker for each utterance (e.g., target student, interviewer, or another student) and the beginning and end of each interview.

System Message Prompts. As shown in Table 5, Approach 1 did not reference a theoretical framework, instead simply instructing GPT to “create a codebook grounded in the qualitative data.” In contrast, Approaches 2–4 asked GPT to “create a codebook grounded in both theoretical frameworks on interest development and the qualitative data itself.” The replication of Study 1 produced codebooks with constructs identical to the four stages of interest development proposed by Hidi and Renninger’s theoretical model, which proved challenging to operationalize in interview coding due to significant overlaps in how they appeared in the data (e.g., Maintained Situational Interest and Emerging Individual Interest). Therefore, we also instructed GPT to expand upon the major categories from the original framework, generating codes that would better capture how these stages manifest in the context being studied. These were the only differences in the system-level prompts across the four approaches.

User Message Prompts. The primary prompt differences, shown in Table 6, were executed in the first stage of the user message. Here, we systematically varied the prompt across the four approaches. Approach 1 (Atheoretical) did not specify an interest theory for GPT to use, and no additional prompts were included in the user message. Approach 2 (Theory Named) specified that GPT should use Hidi and Renninger’s theoretical framework for interest, but did not provide any additional reference information. Approach 3 (Full Reference Given) asked GPT to use Hidi and Renninger’s theoretical framework by providing the full reference for that paper and supplementing it with the reference information for Linnenbrink-Garcia et al.’s (2010) article, which develops a now well-established survey to study Hidi and Renninger’s theory, providing a clear operationalization of that theory. Approach 4 (Papers Provided) asked GPT to use these same two papers by directly providing the full text of each paper, aiming to enhance the model’s ability to generate accurate responses by integrating external knowledge sources.

At the end of this process, GPT was also used to consolidate the individual codebooks obtained for each subset of the data into a single codebook. This was achieved using the following user message (the system message remained the same as presented in Table 4):

The following codebooks were created using qualitative data excerpts from interviews with middle school students playing Minecraft to learn about science and astronomy. The codebook will be employed to analyze interest development of these students.

Your task is to:

1. Combine all individual codebooks into one comprehensive codebook.

2. Identify overlapping codes and merge them into a single code, ensuring consistency in names, definitions, and examples.

3. Preserve unique codes that capture distinct themes or insights from the data.

4. Provide clear and actionable definitions for each code.

5. Include examples for each code from the data, ensuring that the examples are representative and relevant. Provide 3 examples for each code.

Individual Codebooks:

[Insert the individual codebooks here]

Your reply should be the final unified codebook, structured with: Code names, definitions, and examples. The final codebook should be ready for immediate use in qualitative analysis.

Each approach was tested three times to check the consistency of the GPT’s output, generating a total of 12 codebooks (4 approaches × 3 replications).

Evaluation of Codebook Quality

Two types of human assessment were used to analyze differences among the four approaches. First, two human raters (the first and second authors) evaluated the conceptual similarities of the constructs produced across the three iterations of each approach (i.e., 12 codebooks). They also considered the constructs generated in the previous study (Section 4.3). As in Step 3 of Study 1, no new codes were introduced during this refinement process. Instead, we excluded codes that were not applicable to the data set and grouped thematically similar constructs under a single category (see Corbin and Strauss, 1990). As the four new prompting approaches introduced several novel constructs, this codebook (presented below in Tables 7 and 8) differs from the codebook presented in the interest-based replication of Study 1 (above, Table 3). The resulting consolidation and refinement (see Tables 7 and 8) served as the gold standard against which all GPT-generated constructs were compared.

In addition to the construct overlap results, five human raters (authors 6 through 10) independently rated each of the four codebooks, using an instrument adapted from Barany et al. (2024) and Liu et al. (2024), allowing us to compare the four approaches (see Appendix 1). In this evaluation, the five coauthors were asked to re-read Hidi and Renninger’s (2006) foundational article and then assess each codebook on seven dimensions: (1) alignment with Hidi and Renninger’s theory, (2) usefulness for investigating interest development, (3) clarity of definitions, (4) alignment between definitions and examples, (5) concreteness of the codes (i.e., their practicality for coding the given data), (6) exhaustiveness of the codebook, and (7) complementarity between constructs (i.e., lack of unnecessary redundancy). The instrument also included an open-ended question asking evaluators to share any additional thoughts on each codebook. All raters had expertise in the four-phase model of interest development and familiarity with both qualitative coding practices and the data context. The codebooks were presented to the raters in random order without revealing which approach had been used.

Results

Construct Overlap Evaluation

The final combined codebook, derived through human refinement and consolidation of constructs proposed across multiple prompting approaches, contained 15 constructs and is presented in Table 7. The corresponding evaluation of construct overlap (based on this refined codebook) is shown in Table 8. Across the four approaches, many constructs overlapped in both their definitions and examples. For instance, the refined construct Scientific Reasoning consolidates eight GPT-generated codes from the different approaches, including Problem Solving & Strategy, Experimentation & Testing, and Hypothesizing & Scientific Reasoning. Although these original codes highlight different facets of Scientific Reasoning, the data examples provided by GPT for each construct were often nearly indistinguishable to human researchers (e.g., “I’m going to put it on the inside, so then when it explodes, these will fall down there,” for Experimentation & Testing versus “I think it might produce different amounts of radiation depending on heat, or temperatures, or anything like that” for Hypothesizing & Scientific Reasoning).

We also identified constructs whose definitions did not fully align with the examples provided. For instance, the constructs Frustration and Perseverance included examples that did not explicitly convey either emotion or behavior (e.g., “I accidentally wrote the information on the wrong one.”). As a result, these constructs were consolidated under a broader category, Struggling, to more accurately reflect the content of the example sentences. Similarly, constructs related to Engagement with Science Concepts primarily referred to students’ descriptions of physical variables or specific observations within the virtual environment (e.g., “The temperature is 39.1 degrees. Pretty cold.”). These were redefined as Scientific Description to better represent the nature of the examples.

Moreover, the Papers Provided approach once again produced the four theoretical stages of interest development despite the explicit instruction not to do so. These categories—except for Triggered Situational Interest, which was retained as Triggered Curiosity—were excluded from the final human-refined codebook due to their limited practical definition.

Code & Definition | Example Utterances from the Data |

|---|---|